- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In a long career talking to and about politicians, I have learned one thing. While many fantasise about being prime minister, the key driver is to get close to the centre. Christopher Pyne captures this immediately in The Insider, comparing the political world to the solar system in which the skill is to know one’s place relative to the sun (the prime minister), and the aim is to get as close to the sun as possible. To be an insider, to know how things work, with privileged information that few others share, is the allure.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

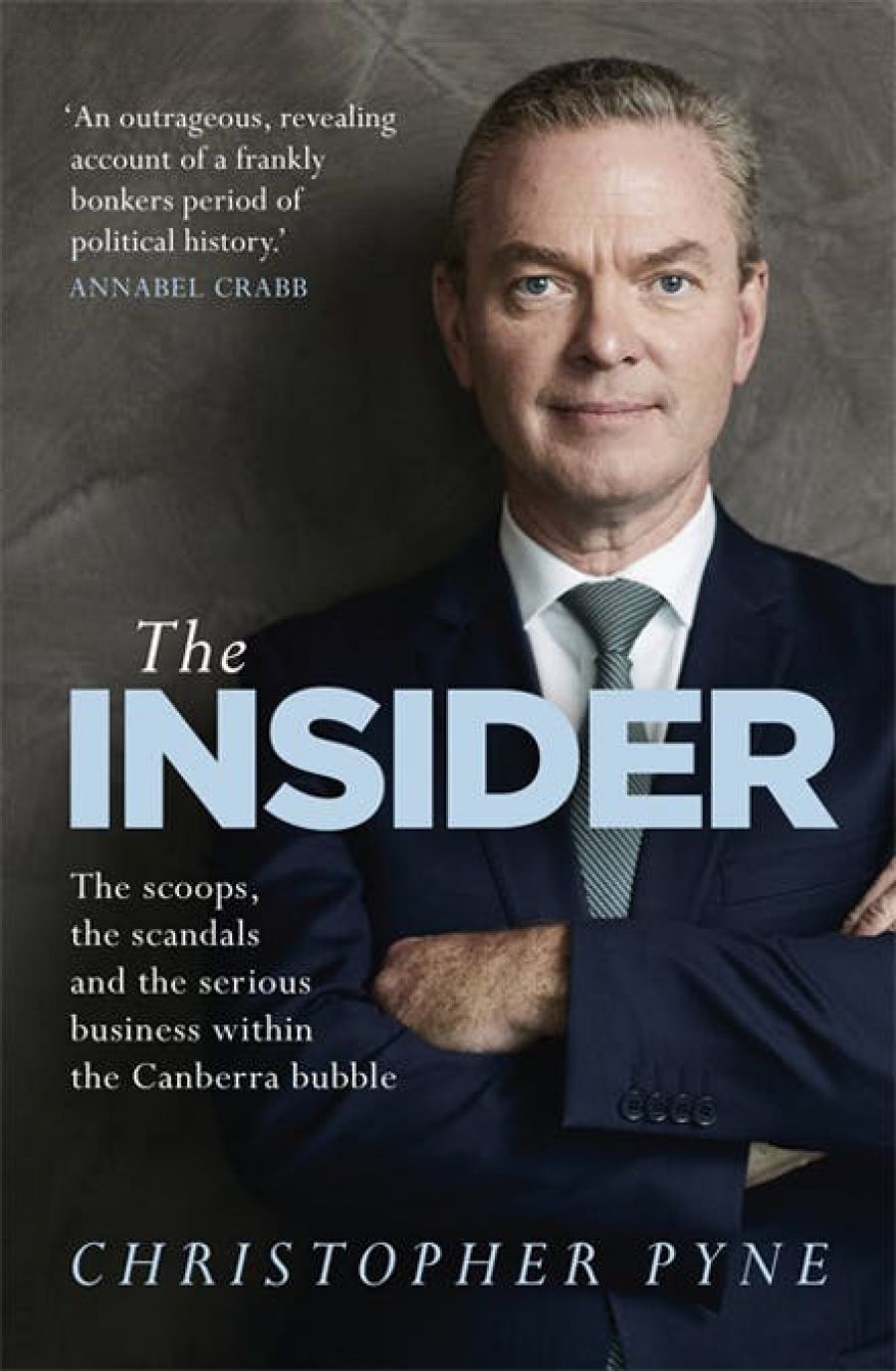

- Book 1 Title: The Insider

- Book 1 Subtitle: The scoops, the scandals and the serious business within the Canberra bubble

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $34.99 pb, 332 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/LQ9rM

Pyne says little about private life, and nothing about the trajectory through party branches, university politics, the Young Liberals, work as a staffer (for Amanda Vanstone), and the first, unsuccessful tilt at election in 1989 that preceded his election to Parliament in 1993. He was twenty-six. This book concentrates on those years when he was, in mid-life, at last close to the action. So we see his frustration at not being quite in the front ranks in the late Howard years; the aggravating ‘winter’ of opposition, facing a ‘hopeless’ Kevin Rudd and a hapless Julia Gillard; and, finally, his triumphs as a senior member of the Coalition executive, and manager of parliamentary business, from 2013 to 2019.

Pyne presents himself as one part Bertie Wooster, a jolly chap whose wit and good company won friends and disarmed others across the aisle and around the world; one part master tactician whose canny management of parliamentary business and sense of what the Liberal voter wanted reinforced the Coalition hold on power; and in large part a warrior who never shied from a fight and always returned as good as he got and ‘rather more’. He scrambled to be in the thick of it. As Vanstone observes, ‘he made sure his hands were on any levers he could grasp’.

It is the warrior template that is the most disheartening aspect of Pyne’s world view. ‘War on all fronts at all times’ is how Pyne characterises Tony Abbott’s success, yet it is the subtext in much of the rest of the book. It breeds partisan antagonism that is the obverse of what Bernard Crick, in his classic In Defence of Politics (1962), illuminated: politics as an activity that resolves differences through contestation, negotiation, conciliation, and compromise between different interests to reach a workable solution to the problem of common rule.

When partisanship is amplified, all issues are seen through an ‘us-versus-them’ lens in which an opponent’s views are deemed unthinkable. There can be no bipartisan agreement on workable solutions. So Pyne delivers well-rehearsed, derisory accounts of Labor policy, familiar to anyone who reads the Murdoch press, castigates the Rudd government (especially its reckless spending during the GFC), and rejoices in reducing Gillard’s putative education revolution to rubble because she once slighted him in parliament.

This is paltry stuff, where the fight is more important than the purpose, the goal is to destroy as much as possible of the Labor legacy, and an agenda of limited policy ambition – stopping the boats, the Heydon royal commission into trade unions, and austerity budgeting (defended as good policy but, sadly, bad politics) – comes a distant second. It is a far cry from the sort of memoir John Howard wrote, which covered the battles but always saw policy intentions as central.

If it were not for the closing chapters of the book, where at last Pyne engages with policy detail – the National Innovation Agenda, and his self-defined transformational role in the Defence Industry portfolio – one would relegate this to the tiresome ‘whatever it takes’ genre pioneered by Graham Richardson. But then again, Malcolm Turnbull claims the Innovation agenda as his own, not Pyne’s. And while Pyne’s arguments for ‘dirigiste’ intervention in the market to sustain Defence procurement and development in Australia – safeguarding industry R&D, promoting STEM teaching and research, fighting against the loss of local knowledge, skills, and jobs – are tenable, they are precisely the arguments that were made for retaining the car industry, which the Coalition gleefully sacrificed.

Christopher Pyne with Malcolm Turnbull in the Australian House of Representatives in 2016 (Matt Roberts/Wikimedia Commons)

Christopher Pyne with Malcolm Turnbull in the Australian House of Representatives in 2016 (Matt Roberts/Wikimedia Commons)

Shallow and blinkered policy analysis may be irrelevant to readers who want the insider story of the internal battles in the Liberal Party, how it became ‘an election winning machine’ despite internecine warfare, and Pyne’s thoughts on the leaders with whom he has worked. So what does he deliver? Well, the warrior demeanour is well to the fore in Pyne’s accounts of party room confrontation between moderates and the right, but he continues to claim friendship with all players while regretting Tony Abbott’s eccentricity, the misjudgements of Peter Dutton and Mathias Cormann, and the need to sacrifice moderate star Julie Bishop once he had ‘called the card’ on the spill that brought Scott Morrison to power.

Pyne continues to admire alpha-warrior Abbott excessively, asking if anyone can think of a more effective opposition leader. Well, I can: the great opposition leaders were those who unified a divided party, clarified its philosophy, and devised an agenda for government – John Curtin, Robert Menzies, and Gough Whitlam. Abbott did none of this: amplifying division was all, and he brought nothing into government. Instead, the Coalition has been learning on the job, fighting over direction (with the ensuing dispatch of leaders) at a considerable cost to addressing serious issues such as energy policy and climate change.

Pyne recognises Turnbull’s gifts, and the potential of his thwarted objectives. He gives a persuasive account of the party room battles (against ‘several’ malcontents) that led to the withdrawal of the National Energy Guarantee, the erosion of Turnbull’s authority, and Dutton’s challenge. When it comes to Turnbull’s downfall, however, there is little that is new for anyone who kept up with coverage at the time, save that Pyne argues forcefully – against journalists such as Pamela Williams, Peter Hartcher, Katherine Murphy and others – that Morrison was loyal to Turnbull, not plotting, or manoeuvring his supporters in successive votes to secure a run through the middle. His warrant for saying so is, ‘I was there’. Yet another who was there, Turnbull himself, concluded that Morrison was ‘duplicitous’. Read each one and draw your own conclusions.

As for the election-winning machine, that is an impressive feat given the turbulence and leadership rotation in Coalition administrations between 2013 and 2019. Pyne’s tactics as manager of parliamentary business evidently paid off. One can be less sure of his claim to understand just what works in winning over ‘Bob and Nancy Stringbag’ (and just think of that as a metaphor for the average Liberal supporter in our diverse, multicultural society). His elucidation of the concerns of ‘quiet Australians’ and his dismissal of the preoccupations of ‘the Canberra bubble’ (in which he spent his entire working life) do not coincide with the more rigorous analysis of voting behaviour presented by Shaun Ratcliff and others in Morrison’s Miracle (Anika Gauga et al., 2020). Nor is he forthcoming about the sophistication of media and social media manipulation that now plays such a significant part in influencing voter perceptions: for that one must turn to Stephen Mills, again in Morrison’s Miracle.

What Pyne gives us is the very model of the contemporary political professional, who has no life experience outside politics, is obsessed with process rather than purpose, and will leverage his insider networks to build a successful post-parliamentary career in lobbying and consultancy. Yet finally, Pyne’s continuing preoccupation with garnering ‘maximum attention in all things’ undercuts his attempt to secure his stature as a man of substance. Repetitious flourishing of lengthy endorsements of his achievement from friends, opponents, and world figures is purposely offset by self-deprecation. Here, the famous wit does not come off. What remains is the impression of a man strenuously trying to maintain unrealistic levels of self-regard by insisting ‘look at me’. Good luck with that outside the Canberra bubble.

Comments powered by CComment