- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Though it is his second country of citizenship, Australia might be classified as J.M. Coetzee’s fourth country of residence. He was born in South Africa and served as an academic at the University of Cape Town from 1972 to 2000; he lived in England between 1962 and 1965, where he studied for an MA thesis on Ford Madox Ford and worked as a computer programmer; and he then spent seven years in the United States, taking his doctorate at the University of Texas and being subsequently appointed a professor at the State University of New York. Since his move from Cape Town to Adelaide in 2002, Coetzee’s global literary reputation has risen significantly, helped in large part by the award of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2003.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: J.M. Coetzee

- Book 1 Subtitle: Truth, meaning, fiction

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury Academic, $44.99 pb, 243 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/v7A1j

- Book 2 Title: A Book of Friends

- Book 2 Subtitle: In honour of J.M. Coetzee on his 80th birthday

- Book 2 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 238 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_Meta/April_2020/A Book of Friends.jpg

- Book 2 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/m7Qr1

Anthony Uhlmann, a professor at Western Sydney University who has collaborated recently on research projects with Coetzee, seeks in his new book to shift the emphasis of Coetzee criticism from politics to philosophy, in line with this new direction in the author’s career. Covering the full range of Coetzee’s fiction, Uhlmann’s primary focus is on how it negotiates with philosophical questions, often of an abstract kind. There is an emphasis here on the development of intuition as a form of knowledge as developed by René Descartes and Baruch Spinoza, together with a stress on ethical imperatives of a collective and collaborative nature. Coetzee’s 1994 novel The Master of Petersburg, insists Uhlmann, ‘allows us to glimpse the difference between passive desires that eat our soul and active desires that allow us to flourish’.

There are several biographical sources directly relevant to this attempt to bring together philosophy and writing practice, and Uhlmann’s work draws constructively on some of them. Coetzee’s own PhD involved the application of theories from linguistics to the prose style of Samuel Beckett, and he subsequently published several dense, scholarly articles on linguistics, while his notebooks and other archival material deposited in 2013 at the University of Texas also demonstrate the author’s close engagement with various poststructuralist critical theorists: Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida, J. Hillis Miller, and others. Uhlmann quotes plentifully from the notebooks, and this material usefully illuminates Coetzee’s fiction, testifying to critic Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s observation in 2014 that he might be considered ‘a creative writer of theory’.

What is not so compelling in this book is Uhlmann’s grander ambition to describe a more general theory about how ‘the idea of intuition is applicable to thinking in literature in general terms’. It is this aspiration that induces him to invoke philosophers such as Spinoza and Henri Bergson, with whom he admits that Coetzee himself had at most an oblique relation. Acknowledging that Coetzee does not address these philosophers ‘directly’, Uhlmann nevertheless suggests ‘there are some implications of Spinoza’s system that align with the formulations Coetzee develops in his PhD dissertation’. Or again: ‘While he is probably not thinking of Spinoza, or Bergson, the concept Coetzee develops through his own intuitions accords with Bergson’s concept of duration.’ Uhlmann suggests this contributes to his own critical claim that ‘there is truth in fiction’, but this seems at times something of a stretch.

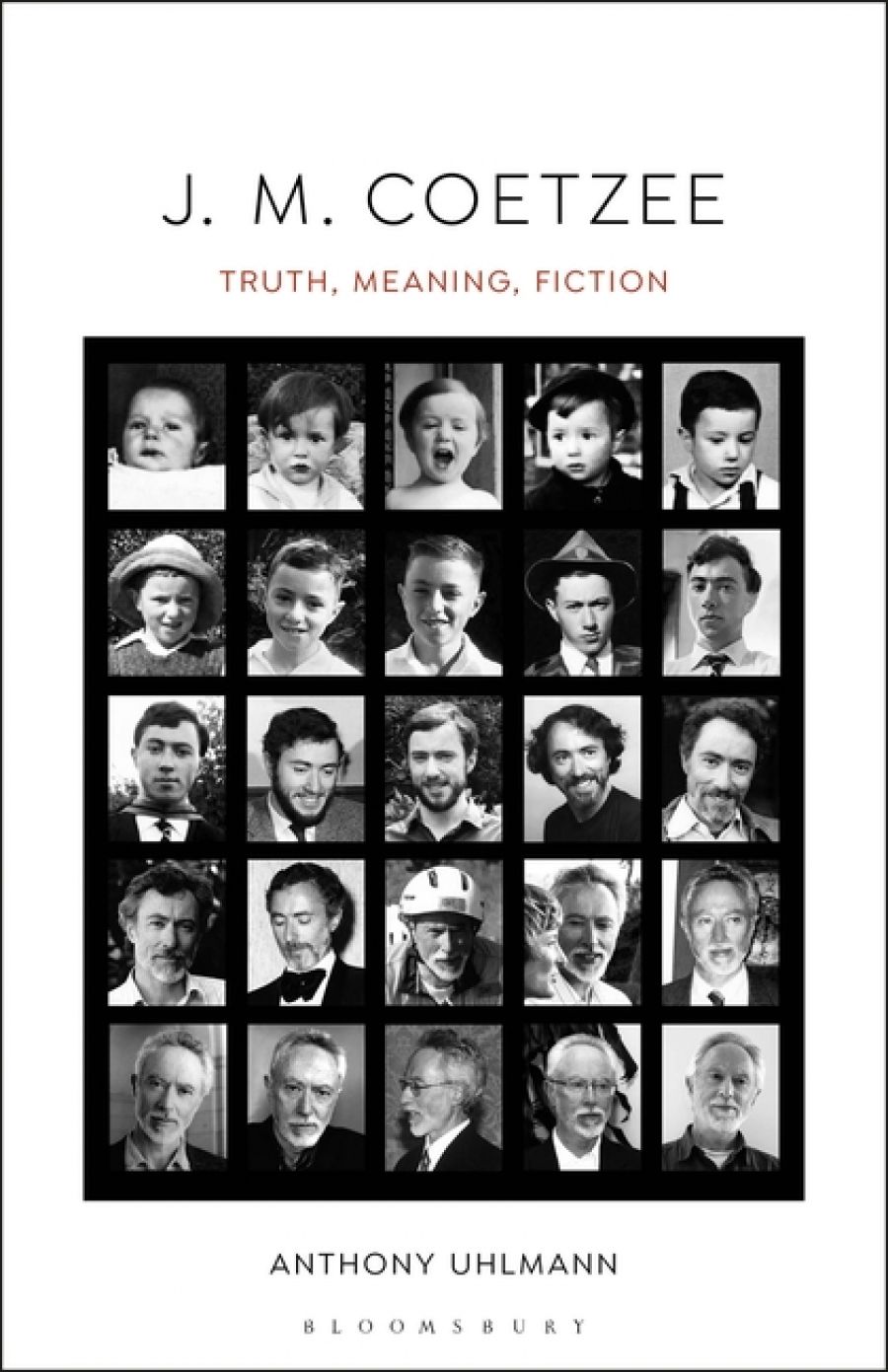

The meticulous scholarship in this book is valuable, particularly in such telling details as the references to Plato in Coetzee’s archives, which can be correlated precisely with a course on Plato’s Phaedrus that Coetzee co-taught with Jonathan Lear at the University of Chicago in 2003. But the critical analysis of Coetzee sometimes seems more cumbersome, as if intellectual agendas from a different kind of project were being interposed here in a counterproductive manner. Still, no book can do everything, and this work should be regarded as essential for Coetzee scholars and academic libraries, if only because of the information it brings to bear from the author’s archives. It also has one of the best covers I’ve ever seen, a ‘life portrait’ of Coetzee by Sharon Zwi, incorporating twenty-five photographs of the author from a baby through to the present day.

J.M. Coetzee (photograph via The Nobel Prize)

J.M. Coetzee (photograph via The Nobel Prize)

Another critical work on Coetzee of a similarly hybrid nature has been edited by Dorothy Driver, who describes herself in the book’s preface as ‘his life-companion over four decades’. A Book of Friends is ‘a gift of love’ that embraces ‘a few of those whose creative work and conversations John has admired and enjoyed in the regions where he has lived or worked’. Again, there is much here that is fascinating, including reproductions of two works of art made by Coetzee’s brother, David, shortly before his death. According to Uhlmann, David was the source of the main protagonist in the ‘Jesus’ trilogy. There are also excellent and informative contributions to Driver’s book from Jonathan Lear at Chicago, who writes astutely of how Coetzee is ‘impatient with living in clichés’, and from Rajend Mesthrie on Coetzee’s time as an academic teacher of linguistics in South Africa.

But this collection is inevitably something of a mixed bag, and some of these contributions seem to be justified primarily by the individual writer’s friendship with Coetzee. Paul Auster, for example, published a fascinating book of correspondence with Coetzee some years ago that ranged widely across international politics and culture, but Auster’s ‘gift’ here, ‘Notes on Stephen Crane’, does not have any obvious relevance to Coetzee himself. It might be possible to infer parallels between Auster’s comments on the American author’s particular empathy for children and dogs and Coetzee’s representation of both his own childhood in Youth and the character of David in the ‘Jesus’ books, but such analogies remain implicit and merely suggestive.

The thematically tangential nature of some of the ‘creative’ responses (from David Malouf, Gail Jones, Nicholas Jose, and others) also appears unusual in a tribute volume of this kind, though perhaps this testifies to the editor’s desire to accommodate a creative rather than critical community, in line with the priorities of the J.M. Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice to which he has lent his name at the University of Adelaide. Nevertheless, the artwork is always interesting – the book includes an excellent painting of Coetzee by Adam Chang – and, as with Uhlmann’s work, there are many bits and pieces that will also be invaluable for future scholarly inquiries. Oliver Mayo, for example, recounts a fascinating conversation with Coetzee about probability, testifying to the author’s expertise in mathematics.

It is interesting as a thought experiment to consider how Coetzee might be read in fifty years’ time, when he is safely dead and has achieved the kind of historical perspective now granted to, say, W.H. Auden, who was transported to Mount Olympus in 1973. It is possible that Coetzee will come to be regarded as a great writer of the in-between state, travelling not only between different countries but also between different philosophical categories and social formations. Just as Coetzee’s fiction veers between mind and body, so it seems at its most compelling when achieving a state of estrangement from material conditions of society that nevertheless remain as intransigently present as the corporeal frame itself. Coetzee’s protagonists can no more transcend the limitations of the human body than they can escape from the political conditions of South African apartheid or from impersonal Australian civility, and it is the tension between these competing pressures that often elicits Coetzee’s most incisive black humour. His recent novels, for example, have sardonic fun with some of the blank words typical of Australian mandarins, such as ‘supervene’ and ‘appropriate’.

Because of this inherently evasive quality, it seems difficult to fit Coetzee precisely into any philosophical template, just as he does not seem the ideal candidate to be happily encircled by a ‘book of friends’. Coetzee is a great Australian writer in part because of the strategic distance his work maintains from civic norms, just as the fiction he wrote in South Africa will surely come to be seen as more powerful because of its detached style, the way it approaches racial politics through the complex framework of power relations endemic to all human situations. As Patrick White, Australia’s first literary Nobel laureate, was officially lauded for having ‘introduced a new continent into literature’ when his actual artistic achievement was darker and less patriotic, so too has Coetzee, Australia’s second literary Nobelist, epitomised not only ‘the surprising involvement of the outsider’, as the Swedish academy proclaimed, but also the outsider’s recalcitrant disengagement. Like Beckett, the subject of his doctoral thesis, to whom perhaps he still bears the closest intellectual relation, Coetzee operates in a paradoxical, doubled-up space, partly in the world but partly, as a matter of strict principle, set apart from it.

Comments powered by CComment