- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

A young Australian radical, who finds academic success later in life, struggles with an inexorable question: what is the relationship between these two worlds: the activist and the scholar? This question animated the life of Vere Gordon Childe, the Australian Marxist and intellectual whose The Dawn of Euro pean Civilization (1925) helped establish modern archaeology, as it has his most recent biographer, activist and labour historian Terry Irving, whose Class Structure in Australian History (1981, with Raewyn Connell) remains a key text.

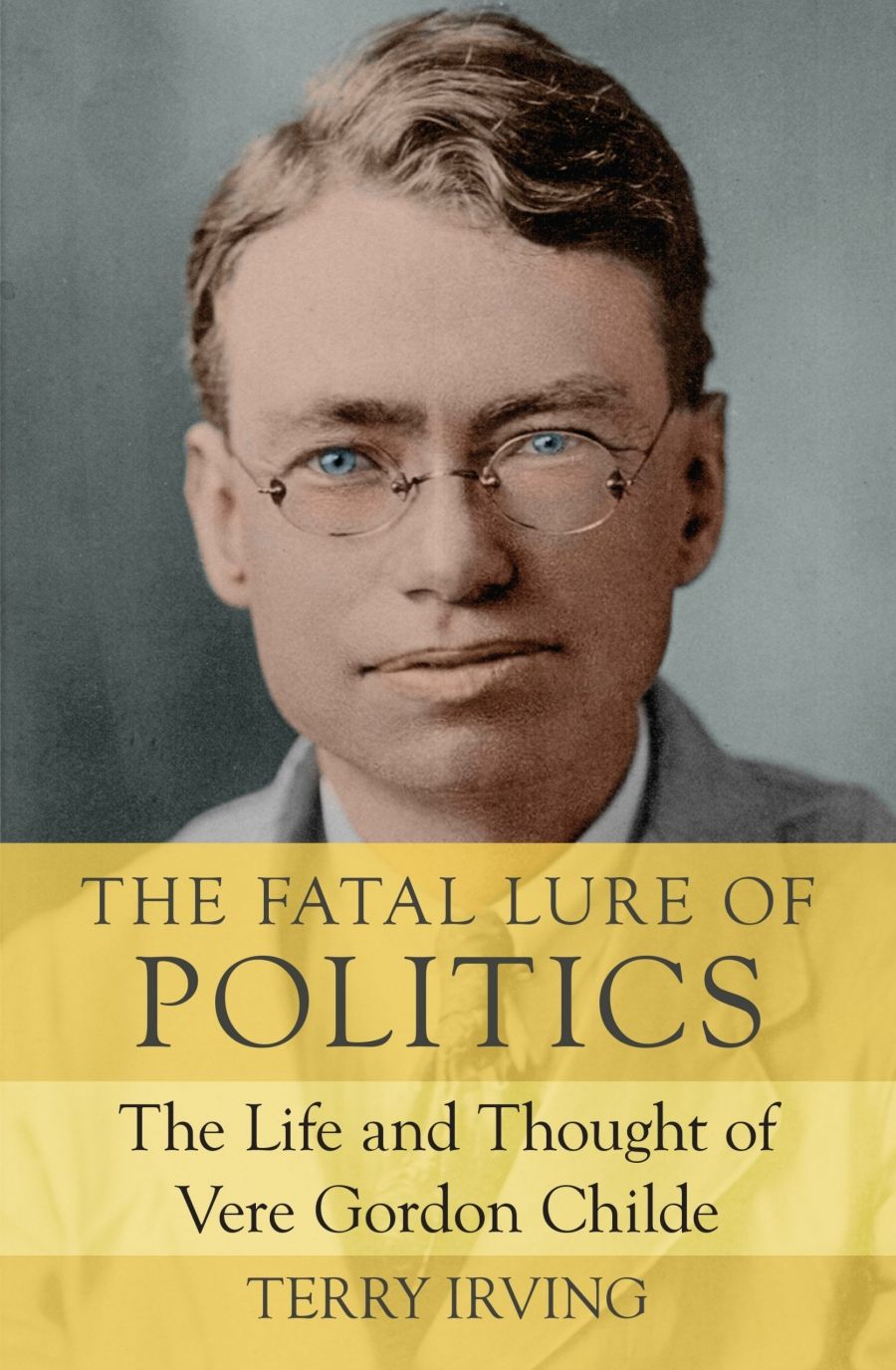

- Book 1 Title: The Fatal Lure of Politics

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and thought of Vere Gordon Childe

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $39.95 pb, 432 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/L997O

Childe the fellow socialist, not the esteemed archaeologist, is the subject of this lovingly crafted biography. Born in 1892 to an ‘enigmatic’ Anglican clergyman in prosperous North Sydney and a mother who passed away before his eighteenth birthday, Childe belonged to the colonial élite. He was educated at the prestigious ‘Shore’ College and then Sydney University, where he excelled scholastically. Extracurricular activities soon placed him among the city’s ranks of radicals. The respectable gentleman-turned revolutionary is hardly an untrodden phenomenon – think of communist and bohemian Guido Baracchi, the subject of Jeff Sparrow’s Communism: A love story (2007) – but Childe’s orientation was different.

Irving’s career as a labour historian is on full display in this volume, as the few extant traces of Childe’s early life are enlivened by the struggles of Sydney’s poor and outcast. He befriended fellow undergraduate Herbert Vere Evatt in 1912, and the pair became enamoured with what they judged to be Australia’s ‘proletarian democracy’. Working for the Australian Labor Party in 1913’s state election and for the Workers Educational Association made Childe a Christian Socialist, a leaning that was challenged at Oxford University, where he undertook further study during the Great War.

There, the bifurcation that would mark Childe’s life became apparent. His increasingly militant opposition to that awful conflagration, particularly its consequences for civil liberty, drove the Australian towards tender friendships with soon to be communists and the attentions of secret police, just as he began seeking employment within his professional discipline. Unsuccessful, Childe returned to Australia in October 1917 ‘philosophically a Marxist and therefore a revolutionary’, though of a more independently minded variety than the newly ascendant Bolsheviks, whom he distrusted throughout his life.

Childe then became a ‘labour intellectual’, a phenomenon to which Irving has devoted decades of study. This interest is apparent in the generous treatment this brief period in Childe’s life receives. Between his return to Australia and his departure in 1921, Childe’s primary role was maintaining peace between the parliamentary wing of the labour movement and its more radical ‘industrial’ wing, which was increasingly sympathetic to syndicalism. He created workable policy ideas that melded the two forces’ main priorities (democratic workers’ control of state-owned enterprises) and, in his position as private secretary to New South Wales Labor Premier John Storey (1920–21), physically distanced the contending parties.

Storey’s untimely death in October 1921 saw Childe, by then back in London as agent-general for the New South Wales government, dismissed from his position. After authoring a scathing indictment of labourism as ‘politicism’, How Labor Governs: A study of workers’ representation in Australia (1923), Childe began to re-establish his neglected scholarly career. This marks a significant segue in Irving’s enquiry: from a study of an emerging labour intellectual to the way in which his flowering scholarly career reflected and complicated these earlier commitments.

Much of this hinges on Childe’s relationship with organised communism. A Marxist in research methodology and conception of history, Childe exercised distance from the Stalinist-led Communist Party of Great Britain. He corresponded with prominent members, including his close Oxford confidant Rajani Palme Dutt, but was judged merely ‘an important fellow and one we have to keep on good terms with’ by one apparatchik. Popular books like What Happened in History (1942) did much to spread Marxist influence in his field and beyond, but the message was carefully sugar coated to ensure palatability for Western liberal audiences.

This is a non-traditional biography in many ways. Irving’s explicitly political focus notwithstanding, any retelling of Childe’s story is complicated by the destruction of his personal papers. As such, we discover Childe through his interactions with others, including Dutt and Evatt, as well as the secret police who intercepted his mail. Significant gaps are filled in with imagination: Irving often entertains the possibility that Childe may have attended a particular event or read a certain book. Childe’s personal life remains a mystery, although Irving offers evidence of his possible homosexuality. The Fatal Lure of Politics is a speculative biography in many ways.

The ‘dual shocks’ of 1956 were as crushing for Childe as they were for many Soviet sympathisers around the world. While Childe was never a true believer, Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin and the subsequent invasion of Hungary in 1956 were compounded by a disheartening scholarly trip, and these left Childe depressed. Perhaps a larger disappointment awaited him in Australia. Announcing his retirement, Childe returned to his homeland to find not the thriving workers democracy he had imagined in 1921 but a complacent society where ‘the working classes have got what they want’: material comfort. While hardly the first Australian to have departed for London only to find his homeland lacking, this lamentation that Australia ‘is far from a socialist society’ evidences alienation from the cause that had animated Childe’s life. His body was found at the bottom of a cliff in the Blue Mountains in October 1957.

It is hard not to detect a hint of autobiography in this engaging book. Irving no doubt sees in Childe’s story the complications he himself has faced as an activist historian: committed to producing ‘usable histories’ for the workers’ movement, but employed by increasingly corporatised, impersonal universities. This productive relationship between subject and author has produced a work that ought to be read widely, and should inform our struggles for knowledge that serves people, not profit.

Comments powered by CComment