- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘The constant loss of breath is the legacy.’ So wrote poet Ali Cobby Eckermann in 2015 for the anthology The Intervention. The eponymous Intervention of 2007 in the Northern Territory was, in the long history of this continent, the first time that the federal government had deployed the army against its own citizenry. As I write this review, in the United States police are using tear gas, traditionally reserved for warfare, against those protesting the worth of black life, while the president flirts with the idea of calling in the military. Some of us gasp in shock. Some, in suffocation.

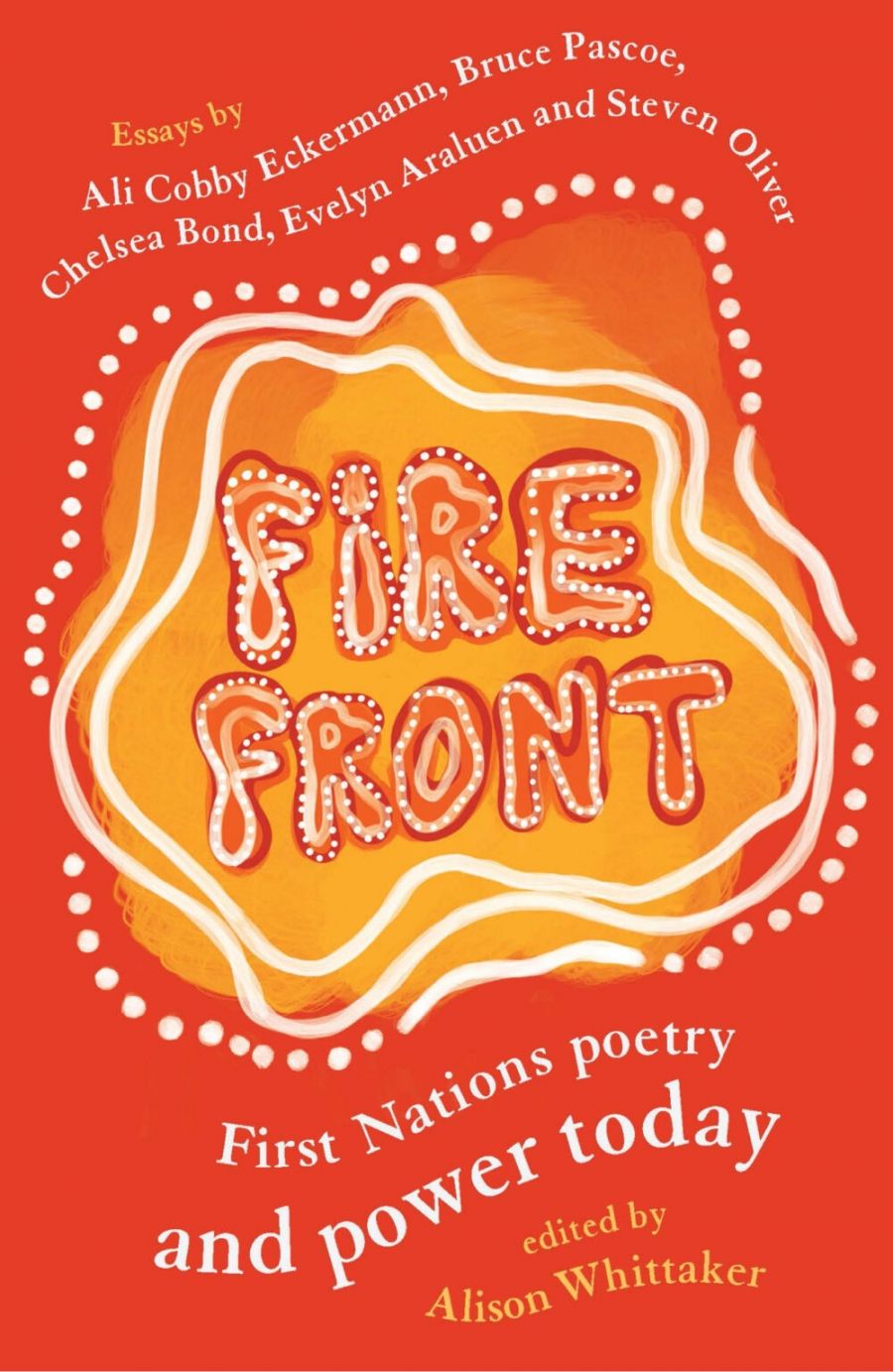

- Book 1 Title: Fire Front

- Book 1 Subtitle: First Nations poetry and power today

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $24.99 pb, 178 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/kxjRL

Fire Front tackles the issue laterally. Avoiding temporal and genre constraints – the anthology as canonical fiat – it offers an opportunity for publishers and readers to consider what it means to place times, communities, and concerns in mutual dialogue. From the oral poetics of Declan Furber Gillick and dropbear poetics of Evelyn Araluen to the fiery bars of Provocalz and Ancestress, the carceral yearning of Dylan Voller to the grim passions of Lionel Fogarty, Fire Front celebrates both the established and emerging, the new and familiar. Each contribution is notable for its vivid, breathing compulsion. Together, they speak with – and toward – a living history.

Some, like Joel Davison’s poem ‘Ngayrayagal Didjurigur (Soon Enough)’, achieve this on two levels: explicitly, by placing Gadigal language between lines of English; and internally, by having the abstractions of the poem’s opening, a weary dialogue of generalised deficiency (‘Wiribay dagura/Worn out and cold [...] Ngarrawan biyal/Distant and no where’) spoken back to by the staunch invocation near its end:

Nabami ngyini

You will see yourself again

Ngyinila

You must

Reflecting on Yvette Holt’s ‘Custodial Seeds’, Steven Oliver’s contribution reveals how, between and among First Nations, respect for difference, combined with a desire to understand teachings that are ‘not my knowledge to know’, can prove generative, reconciling one’s knowledge of self and community. They embody an act of creation: of ‘identity, sovereignty, resistance, pride, affirmation and honouring’.

Equally poignant is Chelsea Bond’s piece on what it means to suddenly find oneself an Elder, welcoming someone whom you have only just noticed knocking at the door – a conundrum made all the more strange upon realising that, the whole time, the person knocking was you.

Mojo Ruiz de Luzuriaga’s ‘Native Tongue’ considers questions of identity and inheritance, the geographical palimpsests irreversibly traced by the history of this continent. Singing of her Wiradjuri great-grandfather and Filipino father, of being born here yet feeling ‘so ill at ease’, Luzuriaga’s refrain – ‘I don’t know where I belong’ – does not render her homeless so much as provide refuge in the act of singing place:

So if you want to call me something

Call it to my face

But I will not apologise

For taking up this space

Following Rio Tinto’s destruction of 46,000 years of cultural history in the Juukan Gorge, Samuel Wagan Watson’s ‘The Grounding Sentence’ is (again) assuming new resonance, speaking back to an ‘eternity of dispersal’. With Fortescue Metals and BHP vying to outdo their competitor in potentially obliterating even older sacred sites, the multiple readings yielded by Watson’s sentence (Verbal? Judicial? Destined?) begin to look, not sardonic, so much as inescapably pained.

How do we write our way out of a destruction that, with breathless velocity, seems unstoppable? Is the constant loss of breath to be the only legacy of this continent?

At present, a petition is circulating to have the New South Wales Attorney General refer David Dungay Jr’s death to prosecutors. Dungay Jr was, among many things, a poet. A stanza of his work closes the petition:

They don’t care, well that’s how it seems

And they take away our hopes and dreams

And until the day we’re out and free

This is how our life’s to be

Fire Front offers another possibility. A vision of First Nations poetry as ongoing work – work begun long before we come to it.

It is a lesson in how to listen; in how to recognise songs that cannot be heard until we are ready to hear – and to honour – what they are trying to say. In this, Fire Front is not so much an anthology as a reckoning. It grapples with our various inheritances and with what can no longer be inherited. Not because it is ‘lost’ (nothing ever is – there is always an imprint left behind by absence, a peculiar bas-relief); rather, because it was never ours to inherit. It was only a guide. A fire to sit with. Until the flames, having subsided, signal that the time has come to move on again.

Epitomising the optimistic vein of Bruce Pascoe, who gestures here toward the pleasures of generosity and patience, the poets of Fire Front sing joy as much as anything else. That spirit which ensured the Ancestors would ‘keep wording, even to the deaf’.

For those who aren’t being heard, our responsibility is to keep listening, learning to amplify their song. Even if we fail, these poems – their indelible grace and compass – will not be lost. They will go on. They always have. They always will.

Comments powered by CComment