- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At first glance, this biography does not look especially compelling. Why should we want to know about Australia’s first woman radio pioneer? But David Dufty calmly and quietly shows why Violet McKenzie is well worth celebrating. From her earliest days, Violet, born in 1890, showed great flair for practical science. She became a high school maths teacher but was determined to study electrical engineering. She qualified, but her gender meant that she was refused admission to the university course and also to a technical college diploma. Meanwhile, her elder brother Walter had become an electrical engineer and was running his own business in Sydney. This was 1912: seduced by the new moving-picture craze, Walter had ploughed all his profits into a ‘flickergraph training school’, teaching people to operate cinema projectors.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

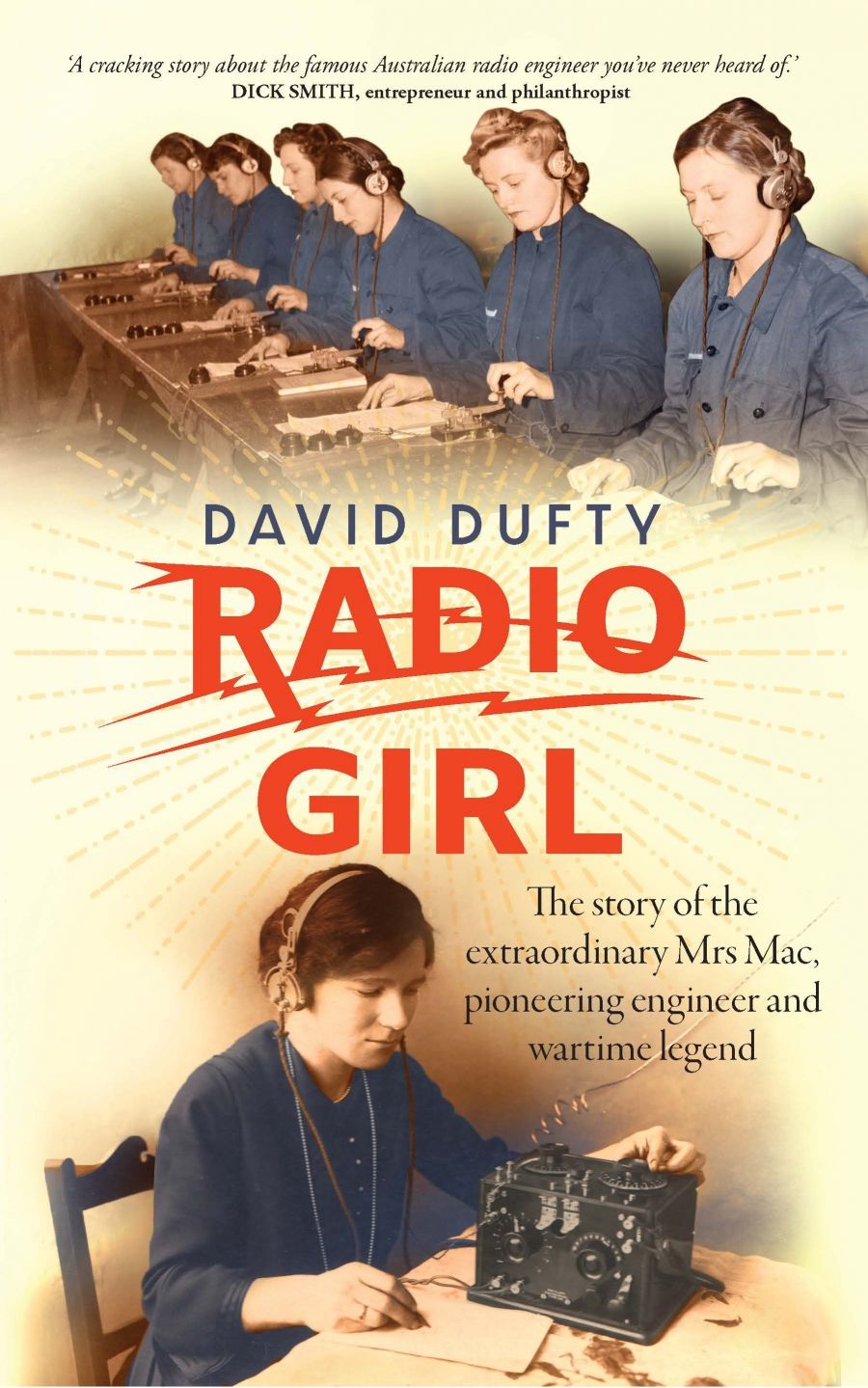

- Book 1 Title: Radio Girl

- Book 1 Subtitle: The story of the extraordinary Mrs Mac, pioneering engineer and wartime legend

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 302 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/jYJev

Unfortunately, Walter went broke and Violet, aged twenty-three, used her savings from several years of teaching to buy him out, setting up her own electrical business, including a shop. After she successfully wired a suburban house, she was allowed to enrol in the diploma course, though not for a degree; she never received one. By the 1920s she was taking on large wiring projects and employing men; council inspectors grudgingly approved the quality of her work, though sometimes they told her she should be at home washing dishes.

Violet’s career blossomed with the advent of radio, a communication revolution. She bought a range of small radio components, which she sold to enthusiastic ham radio operators in her shop. The word spread quickly and people came from all over Australia: Violet’s Wireless Shop became sensationally successful, the Apple shop of its day.

She also saw advantages in helping women understand and use the new all-electric stoves that were gradually replacing gas cookers in many homes. Her All Electric Cookery Book, the first of its kind, adapted standard recipes for the new technology. It sold thousands of copies, even during the worst of the Depression.

When war came again, Violet was a wealthy woman approaching fifty who did not need to work again. However, she set up a school to teach women Morse code, on which signals communication depended. Within six months she had one hundred and fifty students, later increased to five hundred women signallers. She taught them to send and receive Morse code to Royal Australian Air Force standard, as well as training them in the basics of electronics. Knowing that the RAAF was desperately short of competent signallers, she offered it the services of ‘my girls’, but the Advisory War Council wouldn’t hear of that. They even tried, without success, to find retired male telegraphists so they wouldn’t have to hire women.

An exasperated Violet approached the Royal Australian Navy, which was happy to have ‘her girls’ and which eventually employed them to teach Morse code to male cadets. The other services eventually followed suit; by the end of 1941 more than one hundred of Violet’s successful students were working as signallers.

Astonishingly, Violet’s school was being run solely by volunteers, without any payment or subsidy from the Australian government. She was supported by the money she had made in business during the 1930s as well as by her husband, Cecil, an electrical engineer. By the end of the war, she had given signals instruction to almost 10,000 servicemen, from not only Australia but also from the United States, India, Britain, New Zealand, and China.

WRANS holding their hats while visiting the flight deck of a ship (photograph via the Argus Newspaper Collection of Photographs, State Library of Victoria)

WRANS holding their hats while visiting the flight deck of a ship (photograph via the Argus Newspaper Collection of Photographs, State Library of Victoria)

Her work continued after the war. Between 1946 and 1953, almost everyone who became a qualified pilot in Australia – for Qantas, TAA, Ansett, and Butler Air Transport – was trained in signals by Violet’s school. It closed in 1955, but in other premises she continued to train merchant seamen. Violet gave up her school in the late 1950s. She died in 1982, and members of the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service who had been students of ‘Mrs Mac’ formed a guard of honour as her coffin left the church.

A poignant vignette illuminates Violet McKenzie’s character. In 1957 a young sailor struggling with Morse code was told she could help him, even though she had retired. They made no headway until she realised that he had dyslexia, a learning disorder that was hardly recognised at the time. After a lot of work, the sailor passed. (The whole episode could be a scene in a feature movie based on Violet’s life, possibly directed by Bruce Beresford.)

Dufty tells Violet’s story matter of factly, without speculation or writerly flourishes: he does not engage with her inner life. This approach is appropriate for the biography of a woman who was, above all, practical rather than introspective. She dealt with male hostility and sexism by simply ignoring them. The project was the important thing.

Second-wave feminists have tended to ignore the work of women in World War II, possibly because, like Violet, they worked alongside men without antagonism. (Dufty could have spent more time examining this.) But now we have biographies of Marie Curie, Ada Lovelace and her work on early computers, Rosalind Franklin and her work with Watson and Crick on DNA – not to mention the television series The Bletchley Circle. Our pioneer women scientists and technicians are at last coming into their own, and Radio Girl makes a significant contribution to this strand of women’s biography.

A nice touch is the addition of the Morse alphabet and the translation of chapter headings into Morse code.

Comments powered by CComment