- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

For some of us, love for a work of literature brings with it a desire to learn about the work’s gestation. All the literary theory in the world can insist that a piece of writing is not a question to which the author holds the answer, but whenever a book or poem or essay catches our interest, we want to know more about the person behind it.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

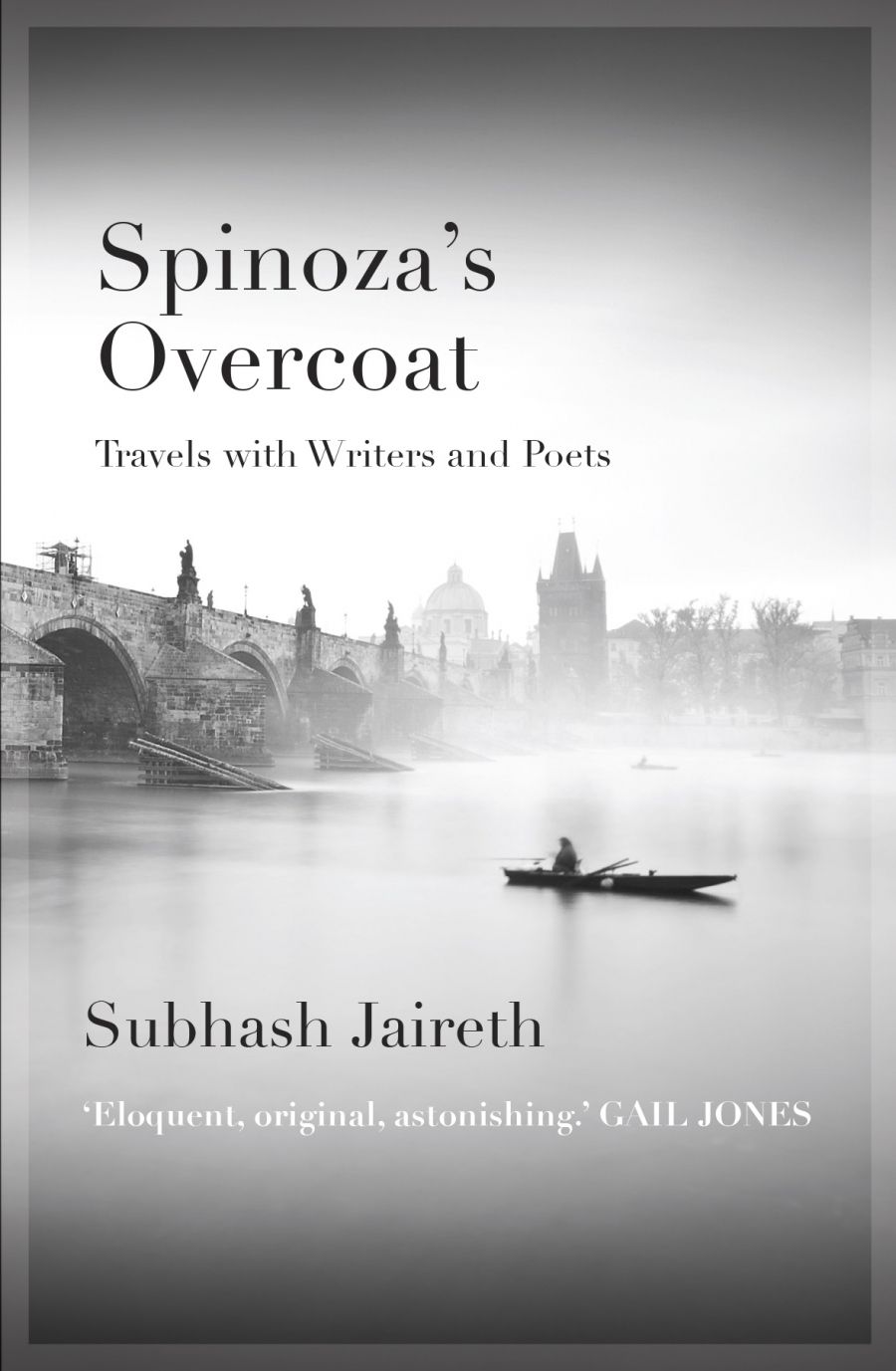

- Book 1 Title: Spinoza’s Overcoat

- Book 1 Subtitle: Travels with writers and poets

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $29.99 pb, 288 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/D7Ryo

The book draws its authority from twin poles, shifting between a dependence on Jaireth’s extensive knowledge of his subjects and then examining his own feelings about them. Jaireth showcases an impressive level of expertise, and each essay constitutes a reflection on how he might balance a considered analysis of an author’s work and style with that love. The repeated grounding of these stories in Jaireth’s own life (his journey to a house in Paris where Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva once lived; a visit to Bulgakov’s apartment; watching a video of famed Iranian poet Simin Behbahani’s funeral) reminds us of how our desire to not just read a writer but to feel as if we know them can be both a foundational pleasure of reading and a fool’s errand. ‘I feel,’ he writes, ‘as if I am looking for a home where I, the prodigal son, can return and find salvation.’

A literary translator and author of poetry, non-fiction, and fiction, Jaireth sometimes seems to be working in the discursive tradition of W.G. Sebald, who is quoted at length in the opening essay. There is a gentle ease to his writing, often conversational and speculative, although, unlike Sebald, there are flashes of excessive ornament and sentiment.

W.G. Sebald (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

W.G. Sebald (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Jaireth often figures writing as organic, a living thing. He imagines Behbahani writing one of his favourite poems: ‘like a loving mother, she would have groomed it carefully before it was ready to walk into the world’. He refers to her poems, which were self-censored to prevent ire from the Iranian regime, as ‘bruised or maimed’. In one essay, Jaireth inhabits the perspective of Pasternak’s poem ‘Hamlet’, which operates as a kind of anthropomorphic vehicle through which to deliver insights into both the life of Pasternak and the texture and form of his poetry. In the title essay, Jaireth takes on the voice of Celan. Such fantasising is always risky, and it does at times sound strange to hear Celan speaking as if he had learnt about his life by trawling through his own archive, with various (and, to be fair, often fascinating) minutiae of the poet’s biography knocking up against each other for the sake of their having been found rather than for their enriching quality.

The most striking thing about Spinoza’s Overcoat is the sense of insistent honesty, with Jaireth confessing every tender thought and self-doubt as he contemplates his attachments to these writers and attempts to make sense of their lives and legacies. Discussing a poem of Celan’s that is painted on a wall in Leiden, Jaireth writes, ‘I don’t want to believe that the editors went for a non- or less-confronting poem of Celan. “Todesfuge” (“Deathfugue”), his most well-known poem, was perhaps too long to fit on the wall. I’m sure it was too confronting as well.’

This remark typifies the frank hesitancy that underpins and links the essays. Jaireth wants to have faith in the editors’ intentions but recognises that they didn’t live up to his hope, each sentence tracking his train of thought. In the opening essay, Jaireth struggles with his own fury at the death of Kafka’s sister Ottla, who was murdered in Auschwitz, her fate partly attributable to Joseph, her non-Jewish husband, who didn’t try to help her flee the Nazis. Jaireth admits that, ‘For Joseph, as readers must have already guessed, I feel contempt. Yet I don’t know his side of the story. To blame him is quite convenient.’ Later, he concludes that, ‘To blame is easy. To feel compassion and to forgive is quite hard.’ Jaireth is contending with how we might stay true to the feelings we develop for those we know only by their writing or their being written about, while recognising that those feelings so often outpace what we can know.

Throughout these essays, Jaireth is in two simultaneous conversations, one with the reader, the other with his subjects. The final essay, for example, addresses Canadian poet Anne Carson directly. He tells her, among other things, about the sadness he feels when reading poems in translation, his sense of loss, and wonders whether Carson feels the same. The wonder Jaireth describes is the curiosity upon which all reading is predicated, the space in which we ask the author unanswerable questions about who they really are and why they really write. Spinoza’s Overcoat rushes in as if to fill that space, wise enough to know it can’t quite.

Comments powered by CComment