- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Hunting Nazis is an almost guaranteed reading pleasure – the joy of the chase, plus the moral uplift of being on the side of virtue. I started Philippe Sands’s book with a sense both of anticipation and déjà vu. A respected British international human rights lawyer with the proven ability to tell a story, Sands should be giving us a superior version of a familiar product. Many readers will remember his book East West Street (2016), which wove together the Nuremberg trial, some family history, and the pre-war intellectual life of Lemberg/Lviv. The latter produced not only Raphael Lemkin, theorist of genocide, but also the lesser known Hersch Lauterpacht, theorist of crimes against humanity, as well as Sands’s maternal grandfather, Leon Buchholz.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

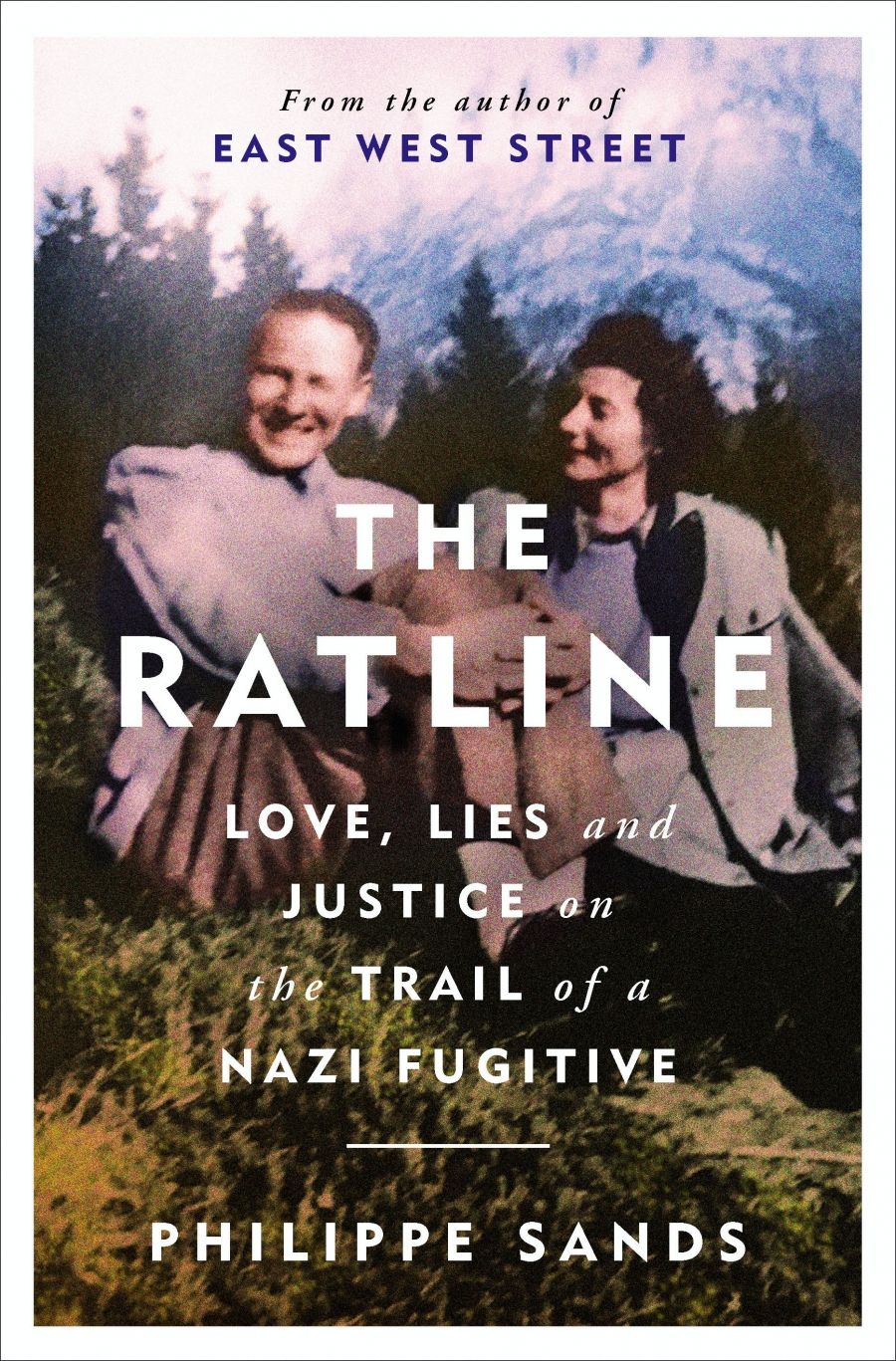

- Book 1 Title: The Ratline

- Book 1 Subtitle: Love, lies and justice on the trail of a Nazi fugitive

- Book 1 Biblio: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $34.99 pb, 432 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/X72Yb

Otto von Wächter, the governor of the Krakow district (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Otto von Wächter, the governor of the Krakow district (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

But Niklas is not Sands’s only friend whose father was a prominent Nazi. The other is Horst Wächter, son of Otto Wächter, wartime governor of Galicia, based in Lemberg, and the subject of The Ratline. Unlike Niklas, Horst – born in 1939 and named for the Nazi ‘Horst-Wessel song’ – is a staunch defender of his father, though not of the Nazi regime as a whole. In 2015, Sands made a BBC documentary called My Nazi Legacy: What Our Fathers Did, which featured the two of them arguing their respective cases. It’s obvious where Sands’s sympathies lie, but what’s interesting is that, even after the documentary and several private conversations in which Sands made clear that he regarded Otto Wächter as a war criminal, Horst continued to invite him to the ‘dilapidated baroque castle’ in Austria, where he had made his home, to supply him with materials from the family archives. That sheds an unusual light on both of them.

The Ratline – which also started life as a BBC documentary in 2018 – tells the story of Otto Wächter and his wife Charlotte from their marriage in the early 1930s, through the war and into the early postwar period. It is based largely on materials kept by Charlotte and which Horst inherited. Otto became a fugitive in the spring of 1945, hiding out first in the Austrian mountains and then, after a brief reunion in Salzburg ended by prying neighbours, in Rome, hoping to get on the ‘ratline’ that took Nazi war criminals from Rome to safety in Latin America. Otto never made it out: in Rome in 1949, a healthy forty-eight-year-old, he suddenly took ill and died. Some thought he had been poisoned.

Otto, son of an ‘ardent monarchist’ general in the Austro-Hungarian Army of Czech descent and an early Nazi, was involved in 1933 in the unsuccessful plot to overthrow the anti-Nazi government in Austria that ended in Chancellor Dolfuss’s murder. He and Charlotte were newly married then. She was in hospital after the birth of their second child when he went on the run to escape trouble after the murder. Otto went to Germany, where he rose through the ranks of the SS. It was two years before the family was reunited in Berlin. When the Anschluss of 1938 brought Austria into the Reich, Otto’s old friend Arthur Seyss-Inquart (Horst’s godfather) became its governor, and Otto a state secretary. In 1939, after the Germans occupied Western Poland, Otto became chief administrator in Krakow (under Hans Frank) before being promoted to the governorship in Galicia in 1942.

Horst – who barely knew his father but felt enormous love and loyalty for Charlotte – always insisted that, to the extent that his father was complicit in killing and mistreating Jews, it was the result of orders from above that he tried to mitigate. There is little evidence to support this, judging by the material at Sands’s disposal, but there is also little evidence that Otto, though a convinced Nazi, was a particularly zealous anti-Semite or enthusiastic killer. He met the administrative challenges of his job to the best of his ability, and he and Charlotte enjoyed the perks and acquaintance with top Nazis that went with it.

Once the war was over, Otto did not waste any time on vain regrets or guilt. Life had presented him with another challenge, this time to stay ahead of his pursuers. Charlotte, never a strongly political person, was also not preoccupied with remorse but rather with looking after her six children and finding a tolerable place in the new postwar world. She kept in touch with Otto, meeting him regularly in the years he was on the run and bringing food, clothes, news, and moral support. While there were obstacles to be overcome by a wife of a leading Nazi official, she was able to find a new home and a job in Salzburg, where her brothers had managed to set up a new business after the war. When Otto went to Rome, she worried, as always, that his eye would stray to other women. Perhaps it did, but Otto’s main occupation in Rome was cultivating contacts close to the Vatican that might help him get out, and avoiding being caught by Allied intelligence, the Soviets, the Poles, or Jewish Nazi-hunter groups. Some of these seem in fact to have been on his trail, although not, apparently, with any marked zeal. Cooped up in a monk’s cell, Otto chafed against the lack of exercise and rashly went swimming in the polluted Tiber River. The mystery of his death, which is nicely played by Sands, is not exactly solved, but Sands does come down with a ‘most likely’ hypothesis which I will not reveal, other than to say that it sounds convincing.

In view of Sands’s propensity to set his lawyerly investigations to music, I wondered if The Ratline would make a good opera. It has the advantage of a female as well as a male lead, plus sympathetic supporting characters in Horst Wächter and Sands himself. For best theatrical effect, he might need to change the ending and play up the melodrama. It is one of Sands’s virtues as a historian that, while he likes melodrama as a narrative device, he builds his analysis on logic and evidence.

Comments powered by CComment