- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

July 1970. A graduate student in English at Columbia University was feeling bogged down in her PhD topic. She was only a year or so in and reckoned that there was still time for her to make a switch from medieval sermons to a modern author. She wrote on index cards the names of numerous writers she liked, including James Joyce, Joseph Conrad, Samuel Beckett, T.S. Eliot, and Virginia Woolf. She then arranged them alphabetically. Beckett came out on top (presumably Auden didn’t make the cut). ‘That was how my life in biography began,’ explains Deirdre Bair, who died in April 2020, in time, fortuitously, to see this book published late last year.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

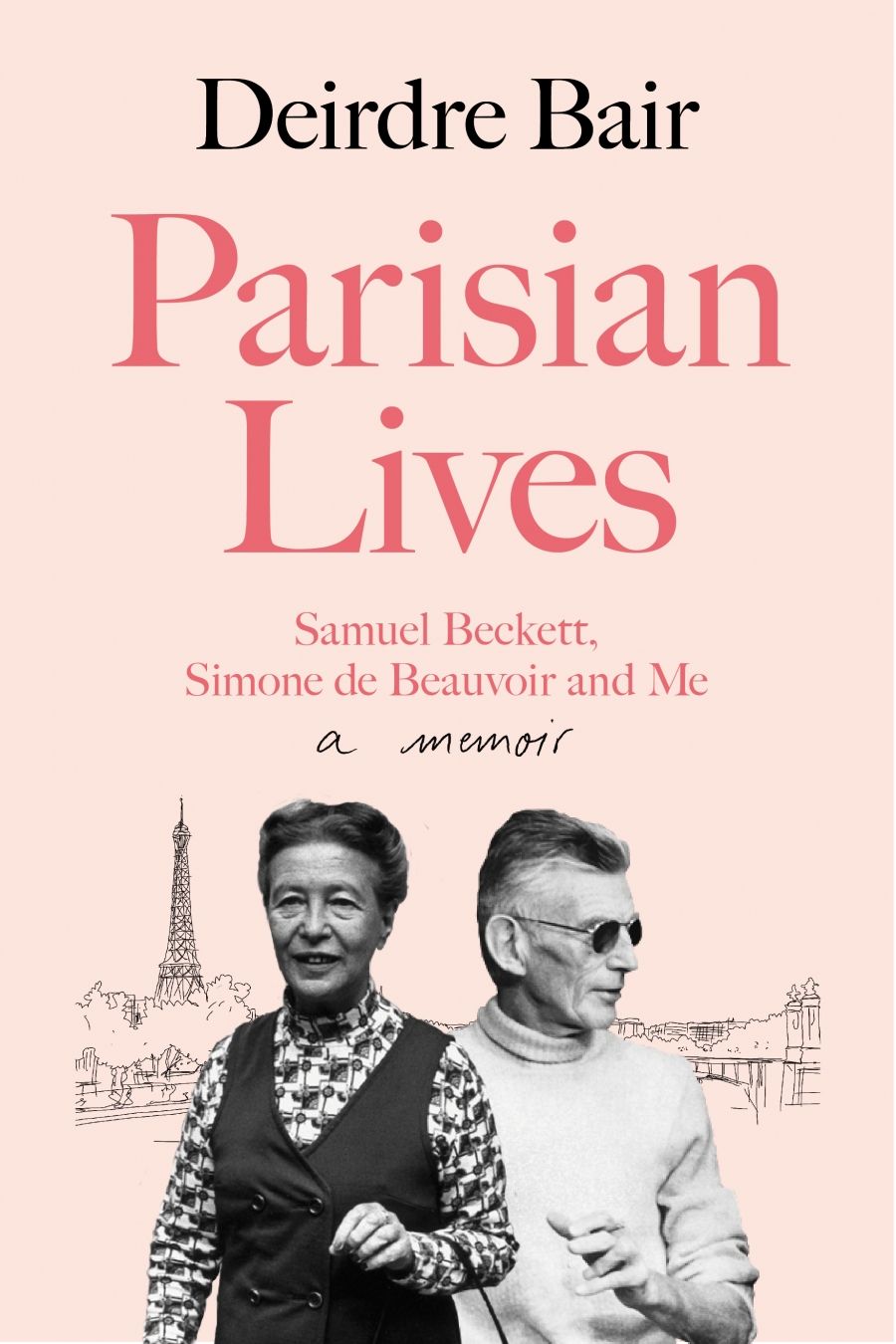

- Book 1 Title: Parisian Lives

- Book 1 Subtitle: Samuel Beckett, Simone de Beauvoir and me

- Book 1 Biblio: Atlantic Books, $29.99 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/V72mM

Although she went on to produce lives on diverse subjects, including Carl Jung (2003) and Al Capone (2016), it remains her first two biographies, those on Beckett (1978) and Simone de Beauvoir (1990), for which she is best known. It is to these two figures, and her experience writing their lives, that this enjoyably candid book is devoted. We find out about both her subjects and their idiosyncrasies. But we also meet the figure who, for objectivity’s sake, stayed marginal in her previous biographies: Bair herself. We discover a young woman overcoming practical obstacles, grappling with self-doubt, emerging from the cocoon of her own naïveté, as she stumbles falteringly into her vocation. While the story is shaped by both hindsight and her own partisan perspective, readers will be appalled by the treatment she received from both the academic and literary establishment and the circles who gathered around her subjects.

Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre attended the ceremony of 6th Anniversary of Founding of Communist China in Beijing on 1 October 1955 in Tiananmen square (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre attended the ceremony of 6th Anniversary of Founding of Communist China in Beijing on 1 October 1955 in Tiananmen square (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

For the Beckett crowd – the ‘Becketteers’ – Bair had more than just jumped the queue. Unwittingly, she had leapfrogged over the entire academic and literary clerisy. Who was this woman with no credentials or scholarly record, who was writing the biography of the greatest living writer? It slowly dawned on her that most, including Beckett himself, did not take her seriously. They assumed that she would never actually complete the biography. She had to push through a gallery of sycophants, bar-room boasters, leeches, and lechers to do so. She is subject to derision and humiliation, including by academics. One charmer tells her at a conference that he well knows what ‘a bitch’ she is. Others insinuate that she only managed to get the biography by sleeping with Beckett or by offering sexual favours to her sources. Her tenacity and determination see her to publication, but the book is greeted by some savage reviews, most devastatingly by Richard Ellmann, author of the justly venerated 1957 biography of James Joyce. ‘Stomping over his desire for privacy,’ he remarks, ‘Deirdre Bair has managed a scoop which in literary history is like that of Bernstein and Woodward in political history.’ (Deliciously, the latter phrase turned up in a later edition as a jacket puff.)

Her Beckett biography undeniably has flaws and errors. Bewilderingly, even here she only admits to one. But its merits far outweigh its deficiencies, and it remains a path-breaking achievement. Parisian Lives sent me scuttling to the Beckett letters to find out what he actually thought of her. In some letters, he speaks warmly of the young American, though she is right that he probably did not think she would finish the biography. He was by and large kind and courteous to her before and after her book’s publication. Her final assessment of him is, in turn, a gracious tribute.

In many ways, Beckett was naïve. He became angry when she tried (as was her job) to uncover things about his personal life: his youthful affair with Peggy Guggenheim; his psychoanalysis under Wilfred Bion. Bair’s biggest coup, for which alone Beckett scholars owe a huge debt, is her deployment of the cache of letters to his friend and confidante Thomas MacGreevy. Beckett’s instructions that they be destroyed were thwarted just in time. They have been a bulwark of academic Beckett studies for decades.

Beckett seems not to have thought through what writing a biography of him would inevitably mean: private aspects of his life made public. It was not until James Knowlson’s 1996 authorised biography (after Beckett’s death in 1989) that his ongoing affair with Barbara Bray, who was highly hostile to Bair, was made public. Biography, Beckett seems to have reluctantly concluded, was a necessary evil, and he probably knew there would be another attempt. Therefore, he chose a decent, thorough, and scholarly academic, one who was sympathetic to him: Knowlson. Bair hints that Knowlson’s book is too hagiographical, which I think is unfair. It is in turn a monumental achievement. But, as Knowlson does acknowledge in that book, he builds on Bair’s foundations, even as he corrects many of her errors.

Simone de Beauvoir lived not far from Beckett but, as Bair discovers, they had an animus, deriving from her early rejection of a piece by Beckett in the magazine she edited with Jean-Paul Sartre, Le Temps Moderne. Bair comes to write the life of this titan of twentieth-century feminism spurred by her own personal experiences of sexism. She vividly captures the process of weaning information from her subject, whose fading grandeur is shot through with vulnerability and volatility. The differences between her subjects are remarkable. Whereas Beckett forbade note-taking of any sort, Beauvoir insisted upon accuracy and record-keeping. She sought to control the content of the biography directly, while Beckett monitored remotely through friends. Beauvoir was cordial, though explosive; on one occasion, she pushed Bair out of the door in a rage. She is attended upon by an adopted daughter, and possible lover, Sylvie Le Bon-de Beauvoir, who is the cause of some of the tension and awkwardness.

Ultimately, Bair feels humbled that her life has intersected with these outstanding cultural figures. That sense of privilege and modesty combine with a winning directness, candour, and clarity. It must have been gratifying that she got to settle some scores before her death. Despite being an ‘accidental biographer’ (the original title for the book), her own life seems propelled through a sort of arc, with her last book granting that elusive sense of an ending which Frank Kermode claims we yearn for but are usually denied.

Comments powered by CComment