- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

John Curtin and James Scullin occupy very different places in whatever collective memory Australians have of their prime ministers. On the occasions that rankings of prime ministers have been published, Curtin invariably appears at or near the top. When researchers at Monash University in 2010 produced such a ranking based on a survey of historians and political scientists, Curtin led the pack, with Scullin rated above only Joseph Cook, Arthur Fadden, and Billy McMahon. Admittedly, this ranking was produced before anyone had ever thought of awarding an Australian knighthood to Prince Philip, but the point is clear enough: Curtin rates and Scullin does not.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

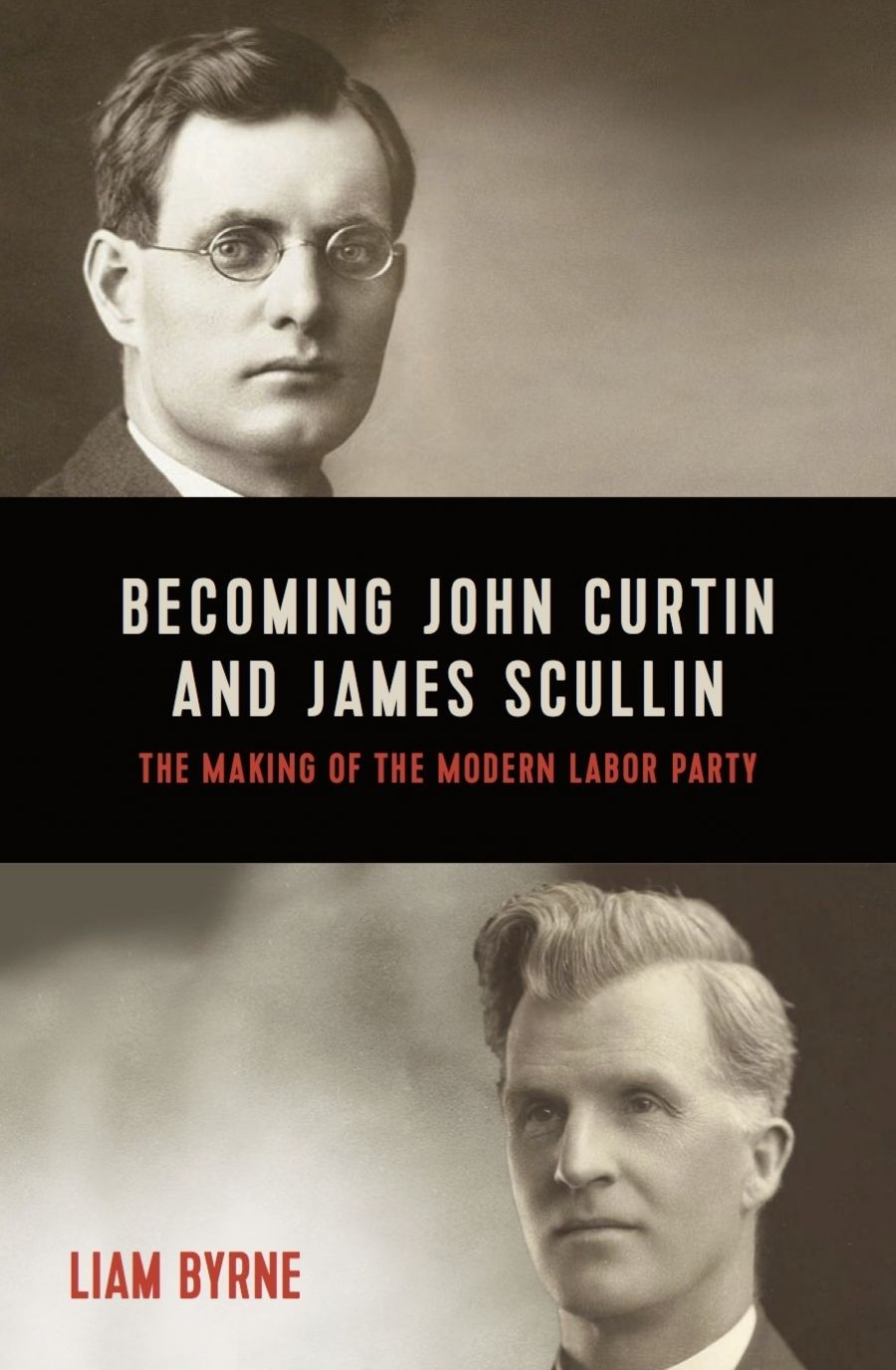

- Book 1 Title: Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin

- Book 1 Subtitle: The making of the modern Labor Party

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $34.99 pb, 194 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/zYnaW

Prime Minister James Scullin in Canberra, 1931 (National Library of Australia, nla.obj-161732766)

Prime Minister James Scullin in Canberra, 1931 (National Library of Australia, nla.obj-161732766)

Byrne’s pairing of Scullin and Curtin draws attention to the entangled lives of these men in the early Australian Labor Party. Both were products of Irish Catholic working-class families from provincial Victoria. More specifically, each came from the Ballarat district, Scullin from Trawalla, Curtin from Creswick. That in itself tells the reader something important. In a highly urbanised country, the country town has been a nursery of political and cultural vitality, and Victorian gold towns especially so.

But gold towns were also places to leave. Both men would head for Melbourne, Scullin some way behind Curtin. Byrne’s subtitle is The making of the modern Labor Party, yet this is something of a misnomer. It is a peculiarly Victorian political milieu that he evokes, and he does that skilfully enough. But Byrne does have a point. While the Labor Party in Victoria was something of a Cinderella among Labor branches until the 1980s, it has exercised a remarkable influence well beyond its borders. It is not just that it generated these two Labor prime ministers. It also produced New Zealand’s first, in Michael Savage in 1935, while the fate of the Victorian branch of the party would be decisive in shaping Labor’s national fortunes – mainly for the worse – in the seemingly interminable Menzies era.

For Byrne, Scullin was a ‘moderate’ and Curtin a ‘socialist’. He treats these as two quite distinct traditions, even allowing that they shared some common ground. I am less certain how meaningful this distinction is for the Victorian labour movement of the early twentieth century. It is true that Curtin’s rhetoric was more aggressive, and he was more willing, as a young man, to contemplate the use of the general strike for political purposes, such as in stopping the outbreak of war. His understanding of the causes of such conflict bears more than a passing resemblance to the ideas of Vladimir Lenin, not least, as Byrne shows, because it had similar roots in the radical liberal ideas of British author J.A. Hobson. But by the end of World War I, Scullin’s understanding was hardly very different from Curtin’s.

Where Curtin cut his political teeth in the Victorian Socialist Party under the mentorship of British socialist Tom Mann and English migrant Frank Anstey, Scullin was closely associated with the powerful Australian Workers’ Union, the successor to the old shearers’ union, a bastion of political caution and pragmatic wheeling and dealing. Byrne does show that Scullin shared some of that organisation’s preoccupation with causes such as land reform. But the AWU was also Scullin’s patron. He first entered the federal parliament as the representative of a rural electorate, and two of his sisters were married to AWU officials. These professional benefits and personal associations may well tell us more about the reasons for Scullin’s close relationship with the AWU than any particular ideological commitment to moderation. It was the AWU that paid Scullin as a country organiser, and the AWU that came to the rescue with the editorship of a labour daily in Ballarat when Scullin lost his seat at the 1913 election.

What is most striking is not the cigarette paper’s difference between the ideologies of two men who regarded themselves as socialists, but the ideas and aspirations they had in common. Both were tribally Labor. Both saw parliament, and not the union movement, as the main pathway to the realisation of their ideals. Both fully understood that Rome wasn’t built in a day, even if Curtin was more inclined to put aside that insight in the interests of his next speech or newspaper article.

Both have been recalled as tragic figures. High office helped ruin the health of each, even if Scullin came to be treated as a failure for his Depression-era prime ministership (1929–32) and Curtin as a hero for inspiring wartime leadership (1941–45). It may well be time to alter this balance. Scullin’s task in the Depression was impossible in a way that Curtin’s job of wartime leadership was not. The economic policy on which Scullin’s government eventually settled in 1931, while not quite what it wanted, rightly received the praise of John Maynard Keynes. A conservative government might not have been able to achieve that without considerable civil disobedience. Meanwhile, the Curtin myth remains so potent and alluring that one sometimes has the suspicion of being taken for a ride. How much was it the strain of war, and how much was it too many cigarettes, too much stodgy food, too much grog, and the temperament of a deep worrier that drove him to an early grave?

Byrne is a lively writer. If Australian labour history has on occasion been a bit dour, it’s not a fault we find here. Of an early communist speaking at a union conference in 1921, he writes: ‘[Jock] Garden replied that he could not outline how to overthrow the system in the five minutes allotted. The conference, therefore, politely granted him an extension to ten.’

Socialism, as Byrne points out, is once again on the political agenda in a way that would have seemed inconceivable in the aftermath of 1989. That has happened for similar reasons to the upsurge of the early decades of the twentieth century: it makes increasing sense as a lens through which to view both the world as it is and the world as it might be. Scullin and Curtin pursued socialism through the Labor Party. Byrne, while critical of the present Labor Party’s lack of vision, is more optimistic than me about its capacity to respond to the challenges and opportunities of our times.

Comments powered by CComment