- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Aboriginal tracker is a stock character in certain Australian films, employed as set dressing, catalyst, curio. Although fictional trackers have been celebrated on celluloid, few real trackers have been given life within the national memory. Some people may recall Billy Dargin and his role in locating and shooting Ben Hall. Others might think of Dubbo’s Tracker Riley, or Dick-a-Dick, who found the missing Cooper and Duff children near Natimuk in 1864 when they had been given up for dead.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

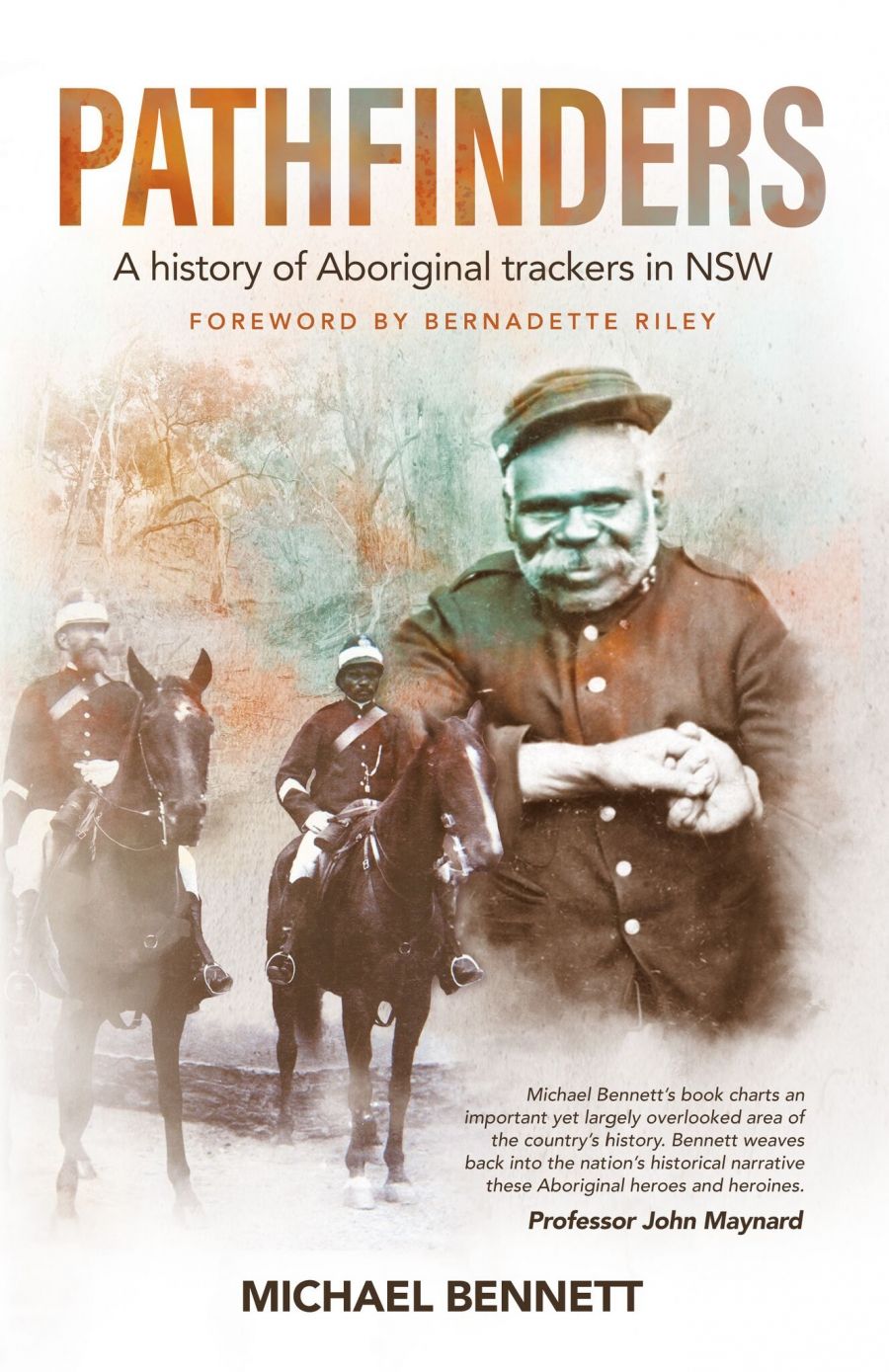

- Book 1 Title: Pathfinders

- Book 1 Subtitle: A history of Aboriginal trackers in NSW

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 336 pp

![]() Tracker Tommy from Broken Hill (photograph via the University of Wollongong Archives)

Tracker Tommy from Broken Hill (photograph via the University of Wollongong Archives)

Many of the tracking feats astonish. Dargin tracked bushranger Gordon Mount for 300 kilometres. George Sharpley spent three days successfully tracking a thief more than 100 kilometres from Lightning Ridge to the Queensland border, over red stone ridges and clay pans. Bennett reports a case in Maitland in 1845 where a tracker noticed an ant carrying a white maggot ‘such as putrid flesh would produce’. This impelled him to dig deep below a stump with a black ant nest, uncovering a corpse. A culprit was found and hanged for murder. No one from 221B Baker Street could have done better.

Bennett’s research foregrounds not just trackers but also some less well-known outlaws. There are the brutal Clarke brothers, responsible for the slaughter near Jinden of four special constables, numerically a greater outrage against police than Stringybark Creek. Bennett lists the astonishing escapes and escapades of Tommy Ryan, and recounts the three-state rampage of Jack Gowanah and Willie Koonamberry. Billy Bogan, a fine tracker who fell foul of the law, reversed his skills to evade capture for almost a year. The same gamekeeper-turned-poacher principle helped the Governor brothers elude pursuers. They climbed through tree canopies and clambered along the bottom rung of wire fences to avoid leaving a trail.

Throughout Pathfinders there are glimpses, sometimes explicated, sometimes at the edge of the frame, of Aboriginal disadvantage. Poverty, violence, racism, forced removals, early death – all the miserable marker posts of the past 232 years. Trackers dwelled in the uncomfortable zone between Aboriginal and settler worlds, grappling with the eternal dilemma of what to do when asked to track their countrymen and women, and with the invidious task of trying to ‘balance loyalty to the job with loyalty to family and culture’. Approval and even acclaim from non-Indigenous Australians came at a cost. As Bennett writes, ‘Even if it is accepted that trackers were largely loyal to their own communities, the fact that they worked for the police and helped protect the economic resources of the dominant white society that exploited Aboriginal people will mean their achievements will not be uniformly celebrated.’

Not that the dank spectre of racism was ever far away. In 1914, early in Tracker Riley’s career, the Dubbo Liberal published an article that commented on ‘the savage nature of these human bloodhounds’, a slur that Bennett believes may have led Riley to briefly resign his post. His career soon resumed, but when he retired in 1950 after forty years of celebrated service, he was denied a police pension.

These stories are told without flash. Bennett is too scrupulous to tizzy up the historical record. Consequently, the book will be met more as a resource than as an entertainment. He has been as diligent as any tracker, working his way through the archives and undertaking original research for decades, evidenced through the copious reference section. His self-imposed parameters – restricted to what, who, when, and sometimes why – allows no incursion into the realm of how. White Australia’s othering of First Nations people and cultures, typically expressed as racial discrimination, slides at the other polarity into exoticising. Thus something as extraordinary as the ability to discern tracks through vast tracts of unhelpful country can be consigned to the category of magic. ‘Spooky Aboriginal bullshit’ is what a character in Dead Heart (1996) calls it; ‘weird Abo shit’ is how it is painted in Welcome to Woop Woop (1997).

How could these trackers do what they did? Was it a quality of seeing, something that extends beyond eyesight? Was it a preternatural capacity for close attention? Was it superior cognitive processing, linking many seemingly insignificant indicators into a narrative? What rarefied intellect can trace pathways through the tangled Australian landscape without compass, topographical map, or SatNav, and is it a feat of remembering or of understanding? These are questions for a different book.

Meanwhile, Bennett’s research should remediate some of the gaudy fictional interpretations. Whereas Rolf de Heer’s The Tracker (2002) portrayed the role’s drama and dignity, the more common filmic approach was exemplified by Journey out of Darkness (1967), where the tracker with quasi-magical powers was played by Ed Devereaux in blackface. The Arrernte man he captured was Malay-born Tamil singer Kamahl. With Bennett’s book for guidance, Australia can do better.

Comments powered by CComment