- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

I read this book about a young woman falling into the dislocating world of a puzzling mental illness at a time when the global pandemic was disrupting many people’s equilibrium. I started to wonder: might living through this time of enhanced anxiety encourage empathy towards people who experience extreme anxiety in non-pandemic times? If those living in the ‘kingdom of the well’ (as Susan Sontag puts it) now start to recognise the contingent, temporary, and often accidental nature of well-being, could that trigger a deeper understanding of those who always live with chronic illness or disability?

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

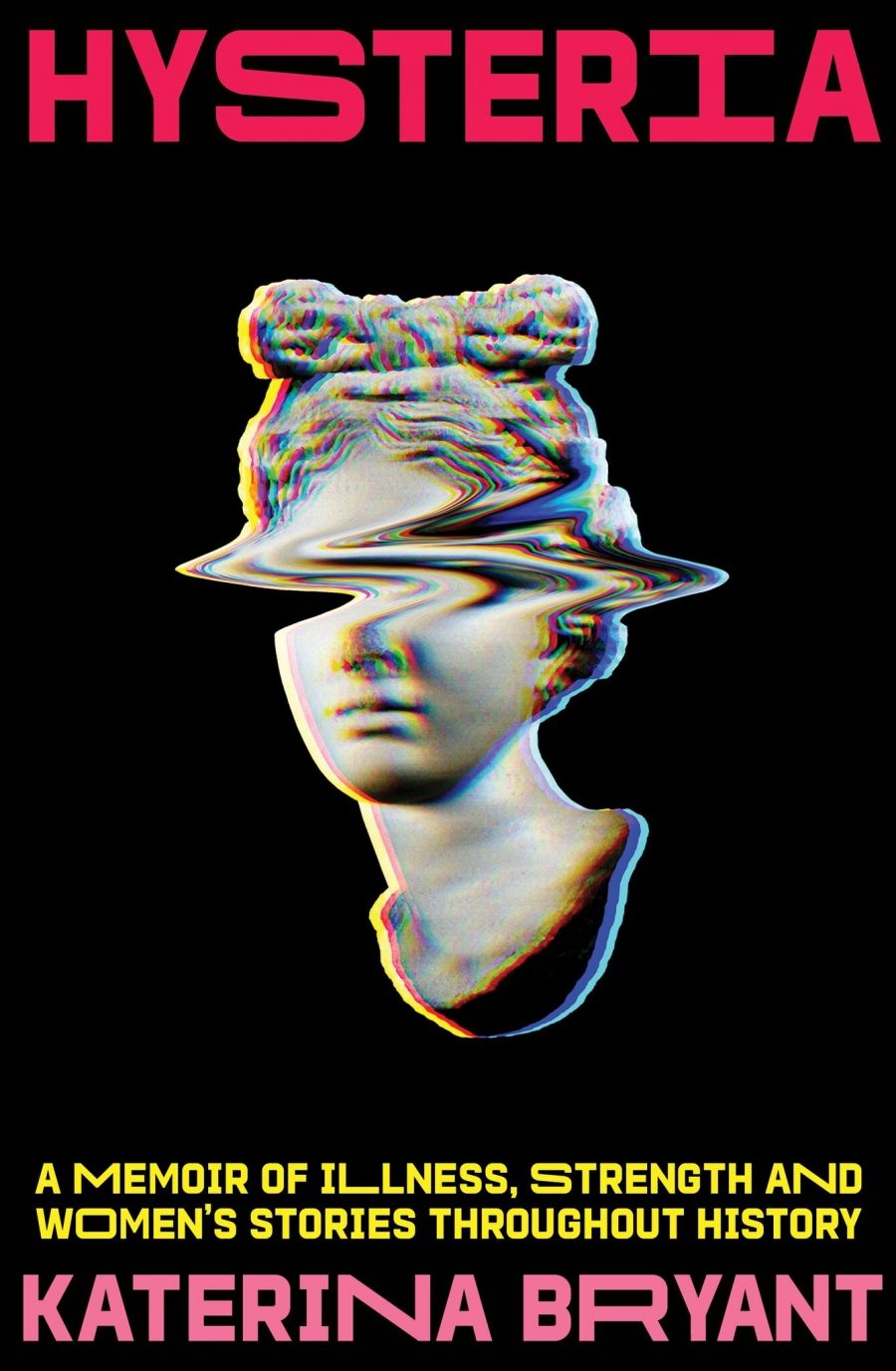

- Book 1 Title: Hysteria

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir of illness, strength and women's stories throughout history

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $29.99 pb, 208 pp

Katerina Bryant has suffered from anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder since she was a child. In her early twenties, she began to experience moments of depersonalisation when she dissociated from all around her, ‘like a cloak taking me out of the world’. The episodes became more serious and more frequent, almost like epileptic seizures. Hysteria is partly the story of Bryant’s search for a reason for the episodes – a diagnosis if you will – and partly an exploration of the lives of four other women who lived with or studied similar illnesses. The way Bryant weaves her own story, which is beautifully rendered, between stories of other women and references to books and films is a strength of this memoir. The reader’s curiosity is always piqued, and yet there is no sense of the gratuitous voyeurism that can accompany some illness narratives.

Bryant’s non-epileptic seizures are a modern incarnation of what used to be known as hysteria (later called conversion disorder). Hysteria, of course, was only diagnosed in women: it was thought to be a malady of the uterus. As Bryant notes, hysteria really signified the lack of a diagnosis, and its manifestations and ‘treatment’ reflected the socio-cultural milieu more than they did any clear medical or psychiatric knowledge or guidelines. In 1602, fourteen-year-old Londoner Mary Glover was subject to exorcism, whereas Blanche Wittmann in the 1880s was probably given an early version of electric shock treatment. Today, medication and psychological therapy are more likely to be offered as treatment.

As well as Glover and Wittmann, Bryant examines Sigmund Freud’s account of his case study ‘Katharina’ in his Studies on Hysteria, and explores the life of German psychoanalyst Edith Jacobson. Bryant learns something from each of the women she studies. Edith was imprisoned (largely for being Jewish) in 1936 in Jauer Women’s Prison, where she continued to practise among the women prisoners. It was there that she described depersonalisation as a result of imprisonment. When she became gravely ill, friends were able to intervene. Edith escaped and moved to New York, where she continued to live and work for forty years. Bryant reads Edith’s life as a form of hope, a suggestion that she, like Edith, can be resilient, can survive.

Katerina Bryant (photograph from Twitter)

Katerina Bryant (photograph from Twitter)

The other stories here are bleaker. Descriptions of Glover’s cold and paralysed body when she has a seizure and the prayers that surround her are chilling. The story of Wittmann (the so-called ‘Queen of the Hysterics’) is tragic: part of her ‘treatment’ was being locked in an asylum, having words about her illness etched on her body, and being publicly displayed by neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot to his peers as an example of hysteria. After Charcot’s death, she remained at Salpêtrière Hospital working as a technician in a radiology lab then dying of cancer from radiation exposure at the age of fifty-four.

In researching and writing about historical instances of supposedly hysterical women, Bryant is fulfilling several purposes. She is reading to try to understand her own experience, to find connections with other women, and to manage her fear and isolation. Narrative, involving as it does a form of linear progression, is a useful coping mechanism. For a writer and scholar such as Bryant, it is a natural way to find order and meaning in the chaos and uncertainty of a complex psychiatric illness. But the book is more than this. It is also a contribution to feminist counter-narratives about women and the way women’s experiences have been controlled, exhibited, and pathologised by the medical and, before that, clerical professions in patriarchal cultures. The stigma of mental illness and neurobiological differences may not result in witch burning or institutionalisation in Australia now, but it still weighs heavily on individuals, contributing to their marginalisation, vulnerability, and poverty. Hysteria offers an engaging and insightful view from the inside of one woman’s experience and sets this story in a larger historical context, laying bare the suffering of women deemed to have hysteria, charting what has changed, and noting what has not yet shifted. In her own words, Bryant is aiming to ‘make severe mental illness something other than abject’.

In fulfilling this goal, Bryant also notes that writing Hysteria ‘healed me of the idea that I could not live with the seizures’. This is no restitution or cure memoir but instead a kind of reckoning. What sort of life can she carve out for herself, now that she understands better the nature of her illness? How can society support and care for – and care about – others with severe mental illnesses? These are good questions for a memoir to explore, particularly in Covid-19 times, when we all see vulnerability in the mirror. In ‘voicing the shape’ of her own mental illness, Bryant may be giving us a way of learning to live with anxiety and fear, a way of looking outwards, with compassion and attention, from the self to the wider community.

Comments powered by CComment