- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

The confusing aspects of this book begin with the title, She I Dare Not Name. Instead, there is a whole book about this person, a self-described spinster. Then there’s the S-word itself, which has carried a heavy negative load since about the seventeenth century. (A minor irritation is the back-cover blurb, which describes this as ‘a book about being human’ – as distinct from being what?)

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

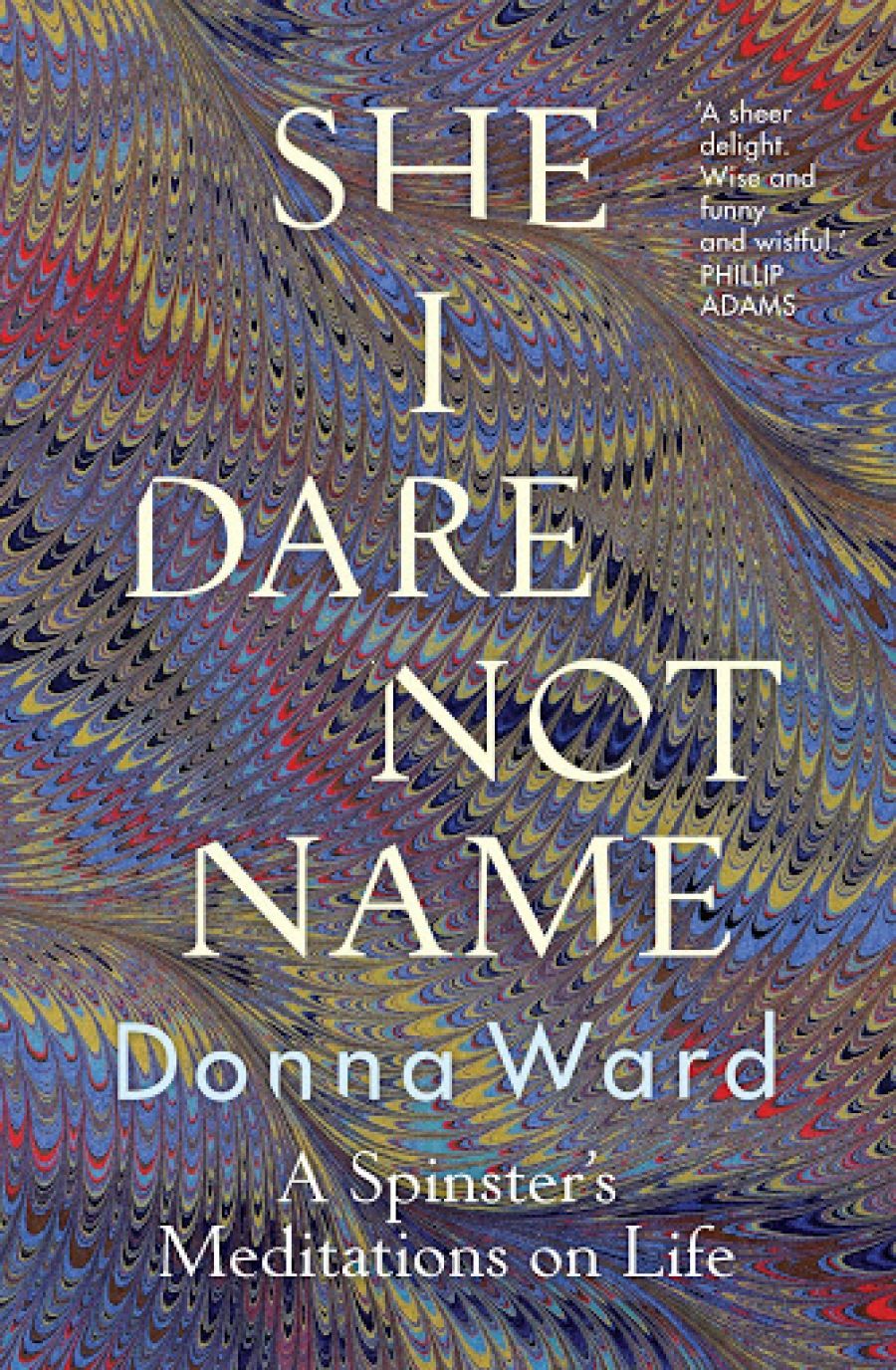

- Book 1 Title: She I Dare Not Name

- Book 1 Subtitle: A spinster’s meditations on life

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 324 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/she-i-dare-not-name-donna-ward/book/9781760876296.html

There is some of that. Ward says, ‘Reclaiming spinsterhood … is to drift into the joy of a room of one’s own … it is to live, work and sleep to one’s own beat.’ She also expands her field of reference by describing others – a man walking to the South Pole, for example – who have perforce come to terms with enforced solitude. This is where she is at her best: there is some beautiful writing about the joys of being alone in nature. Ward is good on the silence of the solitary life, and her descriptions of landscape and climate – especially a huge Perth storm in 2010 – are sensitively observed.

She also has some interesting things to say about the position of single women in Australian society. There is a useful and depressing list of all the things that Gough Whitlam achieved for women, and how much of that was destroyed by John Howard. She also skewers the behaviour of some people when confronted by single women. Anyone who has been, or is, in that situation will surely recognise the ‘so why aren’t you married yet?’ question, and we have all met Bridget Jones’s Smug Marrieds.

But Ward seems overwhelmed by what she has not chosen for herself. ‘I am beyond the balance of intimacy and solitude and deep, deep into the territory of she I dare not name,’ she writes. ‘I am spinster. I stand in grief and loneliness, the fractured paragraphs of a discontinued narrative.’

What are the sources of this grief? Ward mentions a series of failed relationships with men. Instead of discussing the dynamics of these and perhaps looking at what she has expected such liaisons to be, she belittles or dismisses those experiences, coyly giving former lovers names from Greek mythology. Nor does she spend much time on analysing what she thinks marriage and children might give her and what she might give in return. She also writes about friends who, secure in their knowledge that her life is not theirs and that theirs is better, evaluate her in terms of what she does not have. (My response to this was simple: for heaven’s sake, ditch those people and find some friends who will value you for the person you are.) There is quite a lot of this sort of thing, and it becomes annoying.

Ward says that travel helps her deal with her sense of feeling that she is a lesser being because of her single status. She is a practising psychotherapist, and she seems to have enough money, time, and freedom to go when and where she likes. (Aren’t spinsters supposed to be poor and downtrodden?) It’s good that she is able to do this, but from time to time she sails much too close to the rocks of self-pity.

Ward’s sense of what she lacks overpowers many of her insights in the book. She has also fallen into the habit – a trap common to writers of memoir and autobiography – of assuming that all women in her position have the same views as she does. (She states that feminism has rejected all forms of religion because religion is patriarchal. This will be news to feminists who are believers.) Certainly, many woman who have lived alone without family all their adult lives have had pangs of regret about childlessness. But pangs of regret do not a thesis make. In the face of some of Ward’s declarations about the bad aspects of singlehood, I sometimes found myself thinking: Yes? Says who?

In the end, I found this book exasperating, largely because Ward spends so much time harping on the misery of being herself. Her pervasive tone of ‘woe is me’ – the book is introspective without much self-awareness – is sometimes downright alienating. I put this book down thinking that it may be possible to be too much in touch with one’s feelings.

Comments powered by CComment