- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

One of the few details we learn about the unnamed narrator of Ronnie Scott’s début novel, The Adversary, is that he is fond of Vegemite. Although only a crumb of information, this affinity for the popular breakfast tar reveals much about our hero. Just as Vegemite ‘has to be spread very thin or you realised it was salty and unreasonable’, his human interactions give him a soupçon of a social life, a mere taste that never threatens to overwhelm his senses.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

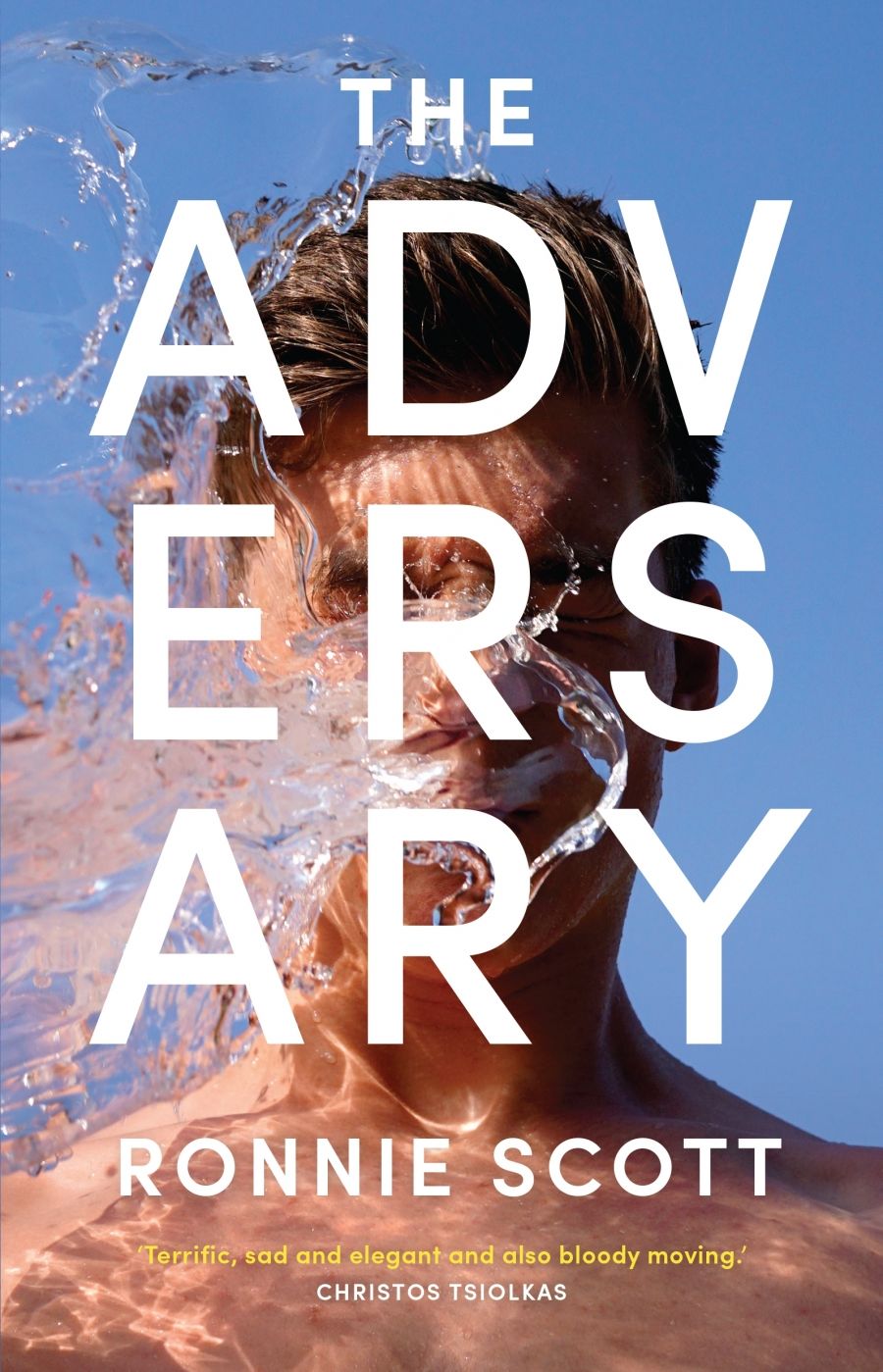

- Book 1 Title: The Adversary

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, 256 pp, $29.99 pb

This confusion is a welcome reminder that knowing one’s sexual orientation does not by itself unknot the complicated and highly individualised question of exactly what it is we desire and from whom. Wisely, the novel never clarifies how we are supposed to feel about the narrator’s social quarantine – is it cowardice or courageous non-compliance? In this way, The Adversary brings to mind another enigmatic novel, Otessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018).

Our narrator does eventually upend his routine of endless showers and lonely binge-drinking. He ventures into the world with the most 2020 resolution imaginable: ‘make friends other than internet and sex people’. His impetus is the looming absence of Dan, housemate and friend, who has a serious new beau in the handsomely blank Lionel: ‘my friend had been substituted with a boyfriend … the real Dan was drip-fed nutrients in some basement cocoon, swaddled up in bodysnatcher ooze’. Dan is the book’s best character, his mercurially shifting moods leaving the narrator feeling ‘respected one second, extremely small and laser-scrutinised the next’. It is not hard to see how Dan’s mix of detachment and disarming tenderness intoxicates the narrator, although their relationship seems to be less protégé-and-mentor than experiment-and-scientist. In one hilarious scene, Dan reacts to the narrator’s confusion with clinical chill: ‘This is why I was right to make you go out and meet people. Everyone should be able to interpret human scents.’ Desperate to replace Dan or become a person interesting enough to retain him, the narrator sets out into the Melbourne summer, where hijinks ensue. He trips and mumbles through a series of lovers and mishaps, although the action is mostly low-key. Those expecting self-discovery via the exotic or erotic, à la Andrew Sean Greer’s Pulitzer-winning Less (2017), may find their blood cooled a bit. Scott’s talents reside instead in dry-ice descriptions of the approximate, the tantalising, the not quite sensual: ‘we didn’t really know how to touch each other properly; we lay on our sides, propped up on one arm, sort of lazily batting each other’s chests and stomach’. One can almost hear the Hollywood string section’s befuddlement when a belated kiss is described as ‘how a mouth could taste, as long as you were busy thinking about real estate’.

Ronnie Scott (photograph by Gina Cawley)

Ronnie Scott (photograph by Gina Cawley)

Despite being fairly light on incident, the book still feels dense due to the narrator’s indefatigably neurotic voice, which is part Woody Allen, part David Foster Wallace footnote. Although it is hinted that the narrator is studying literature, he seems more like a talented but over-exuberant first-year sociology student, his rapid-fire brain unable to let the slightest human interaction go unparsed: ‘Two strangers jogged past, a demonstration of social innocence, a model by which two people could pass by two others, and everyone could choose their preferred level of involvement.’

It is ironic that the narrator sweats off an ecstasy comedown while promising to never again ‘do anything that didn’t have an off button’, because his brain is its own perpetual motion machine, spitting up questions quicker than they can ever hope to be answered: ‘where to put my hands? Who to marry? How to sit?’. This voice will probably be the book’s most divisive quality, its Vegemitiness, if you will, but those who enjoy Scott’s essays and his stewardship of the offbeat literary magazine The Lifted Brow will likely vibe with his character’s ability to explain how disinterest from a crush solves the Fermi paradox: ‘maybe it was just that other civilisations were boring, and Vivian-like societies knew we weren’t worth their time’.

These word swarms are offset by moments of quiet observation that ring all the louder for their contrasting simplicity, such as the narrator’s haiku-like wonder at how digital flirting can so quickly become an IRL body: ‘This person, basically nude, so different from those pictures. The way someone could end up here, a stranger and you.’ The novel itself maintains this online-era blend of intimacy and distance throughout, inviting us into the inner life of someone so compelling that only at the affair’s end do we realise we never even knew his name.

Comments powered by CComment