- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Ornithology

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

It’s late July and high over the foggy green waters of the Sea of Okhotsk, a solitary Grey Plover beats its way south. Within sight of Sakhalin Island, the former Russian prison colony documented by Anton Chekhov, she veers west, heading for a vast tidal flat in Ul’banskiy Bay, not far from the rural settlement of Tugur Village. It’s hard to imagine a more isolated situation, and yet even here, in this empty theatre of sky and water, there is an audience. Nestled under the plumage on her back is a small satellite transmitter. An aerial extending beyond her tail feathers broadcasts her progress to the world.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

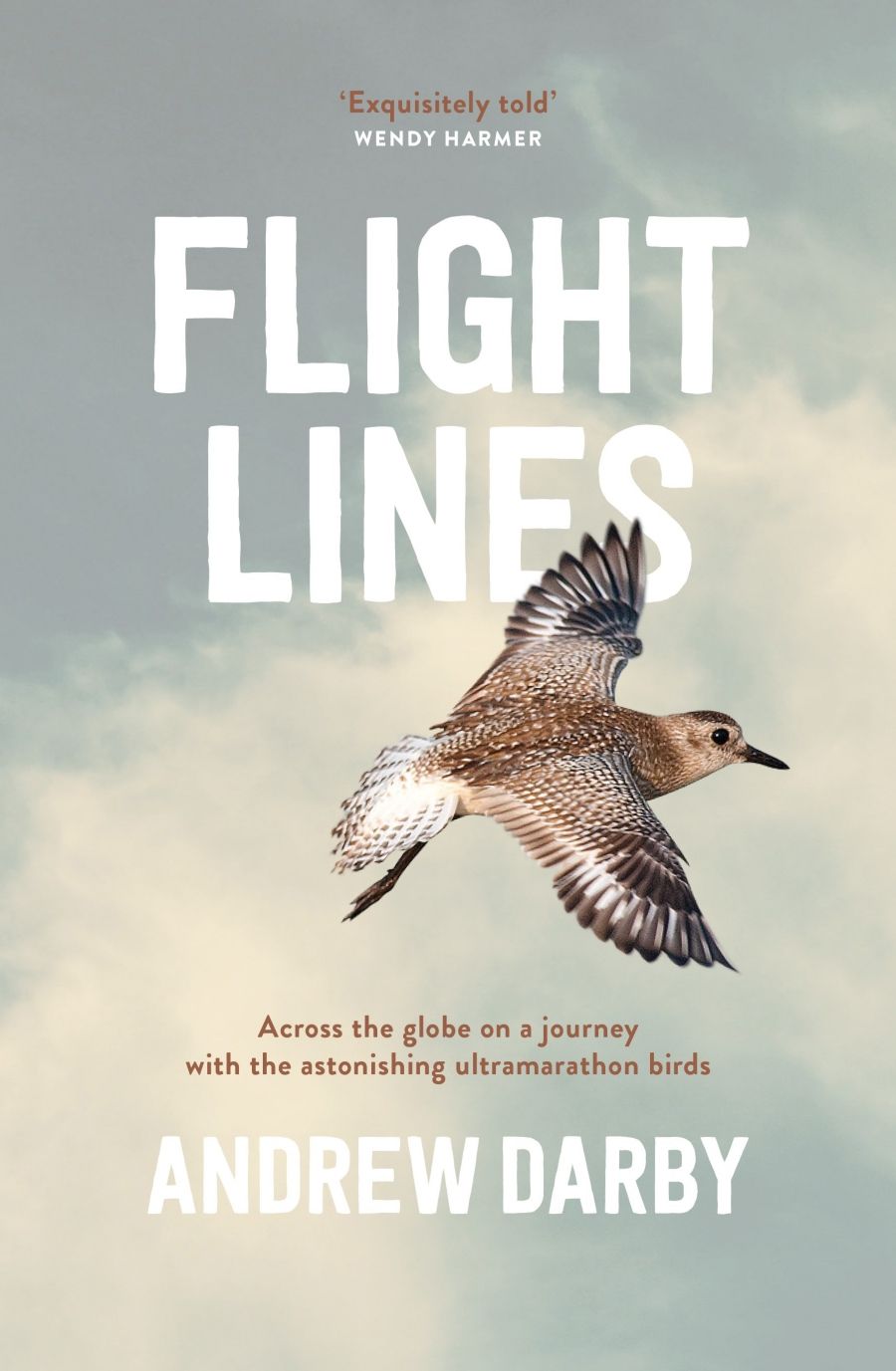

- Book 1 Title: Flight Lines

- Book 1 Subtitle: Across the globe on a journey with the astonishing ultramarathon birds

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 335 pp

The history of our pursuit of migratory birds goes back a long way. As early as 1804, the Franco-American ornithologist and artist John James Audubon was tying lengths of silver wire to the legs of Eastern Phoebe nestlings caught in the woods near his house in Pennsylvania. He wanted to know if the same birds returned to the same breeding sites every spring. Some ninety years later, Danish prodnosing naturalist Hans Christian Cornelius Mortensen inaugurated the modern practice of bird banding by clamping metal rings on the legs of European Starlings and other species. Mortensen’s experiments with hand-bent strips soon inspired others. The practice spread rapidly around the world.

Today, many millions of birds are banded every year by scientists and citizen scientists. Metal rings are sometimes combined with colourful plastic bands that can be interpreted by observers from a distance, without the need for retrapping the birds or shooting them. Neck collars, nasal saddles, and piercings are also used. More recently, shorebirds have been tagged using ticky-tacky colour-coded plastic flags that stick out from the leg and can be read at even greater distances.

Thanks to advances in the design and miniaturisation of electronic tracking devices, we are in the midst of another revolution in the quest to surveil our feathered friends and peer into the mysteries of their migrations. As with whales, wolves, and wallabies, the movement habits of waders can now be scrutinised in real time. Exact flight paths can be plotted. Breeding sites and wintering grounds can be connected. Staging areas can be identified. Distances can be tallied. Feeding patterns and breeding successes can be deduced. Environmental pressures can be identified and monitored.

Grey Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) in winter plumage, at Mølen near Larvik, Norwa (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Grey Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) in winter plumage, at Mølen near Larvik, Norwa (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

In Flight Lines, Australian journalist and nature writer Andrew Darby tells the story of two Grey Plovers trapped and tagged in southern Australia and tracked to an island fastness deep in the Arctic Circle. He retraces the parallel paths taken by the birds, visiting the places they visited, documenting the threats faced by migratory birds along the way, and reflecting on the way technology changes how we think about the natural world.

The Grey Plover, like most shorebirds, lives on the hard-to-reach margins, on mudflats, tidelines, and wetlands, on beaches piled with fetid seagrass wrack, and on exposed sandbanks patrolled by biting insects. We have been slower to accumulate knowledge about its migratory behaviour in our flyway (the East Asian-Australian Flyway) by comparison with other waders, and yet we know that the Grey Plover’s annual transit is one of the most ambitious, shuttling between extreme ends of the world. Darby’s two females, for example, were tracked from Thompson Beach in Gulf St Vincent to Wrangel Island in the East Siberian Sea, last known home of the woolly mammoth.

This and subsequent tracking projects have gone some way toward filling out the picture. It confirmed the importance of the threatened tidal flats of the Yellow Sea. Darby describes the deleterious impacts of hunting, pollution, wind turbines, and, most ominously, land reclamation and the construction of hard coastlines in coastal Chinese provinces like Jiangsu and Hebei. Over the past three decades, vast stretches of the Chinese and South Korean coastlines have been transformed by seawalls and breakwaters, with much loss of shorebird habitat. Ironically, the undeveloped western coast of North Korea is now something of haven.

Darby doesn’t soft-pedal the dangers faced by shorebirds, but Flight Lines is not a doom-and-gloom narrative. The tone is more often one of wonder and curiosity. But what is more wonderful, the birds or the gadgets? Darby is dutifully impressed by the achievements of his two ultramarathon migrants; but what really seems to inspire him – and a lot of the people he interviews – is the achievement of tracing these plovers across three continents.

Indeed, this book has the atmosphere of a boffin’s pilgrimage as Darby searches for totems and symbols along what he calls the ‘arc of possibility’, the zone of potential staging grounds in East and South-East Asia. Darby was diagnosed with cancer during the writing of Flight Lines. He describes how his interest in satellite telemetry helped him to survive this terrifying and profoundly depressing experience. He even suggests that the positive results of his immunotherapy treatment justify, or in some way connect with, the work of gathering data about bird migration.

And so this book, on top of everything else, is a statement of faith in the scientific method. It is, however, sometimes hard to credit Darby’s belief that science will save the birds. Surveillance doesn’t in itself do very much for them. Conservation efforts are helped by access to good data and scientists have an important role to play in shaping the debates that determine how the business of the world is conducted; but the really needful thing is and always has been political willpower. That seems to be in short supply.

Comments powered by CComment