- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Plants are one of the first things you notice when you arrive in Australia: the swathes of olive-green trees and a crisp eucalypt scent on the air. It was the first thing many explorers noted, too, whether in Abel Tasman’s 1642 description of an ‘abundance of timber’ or in Willem de Vlamingh’s 1694 descriptions of trees ‘dripping with gum’ and the ‘whole land filled with the fine pleasant smell’ of native Callitris pines. It did not take long for accounts and samples of Australian vegetation to make their way back to Europe, although it took significantly longer for any systematic scientific work to be completed on our distinctive flora.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

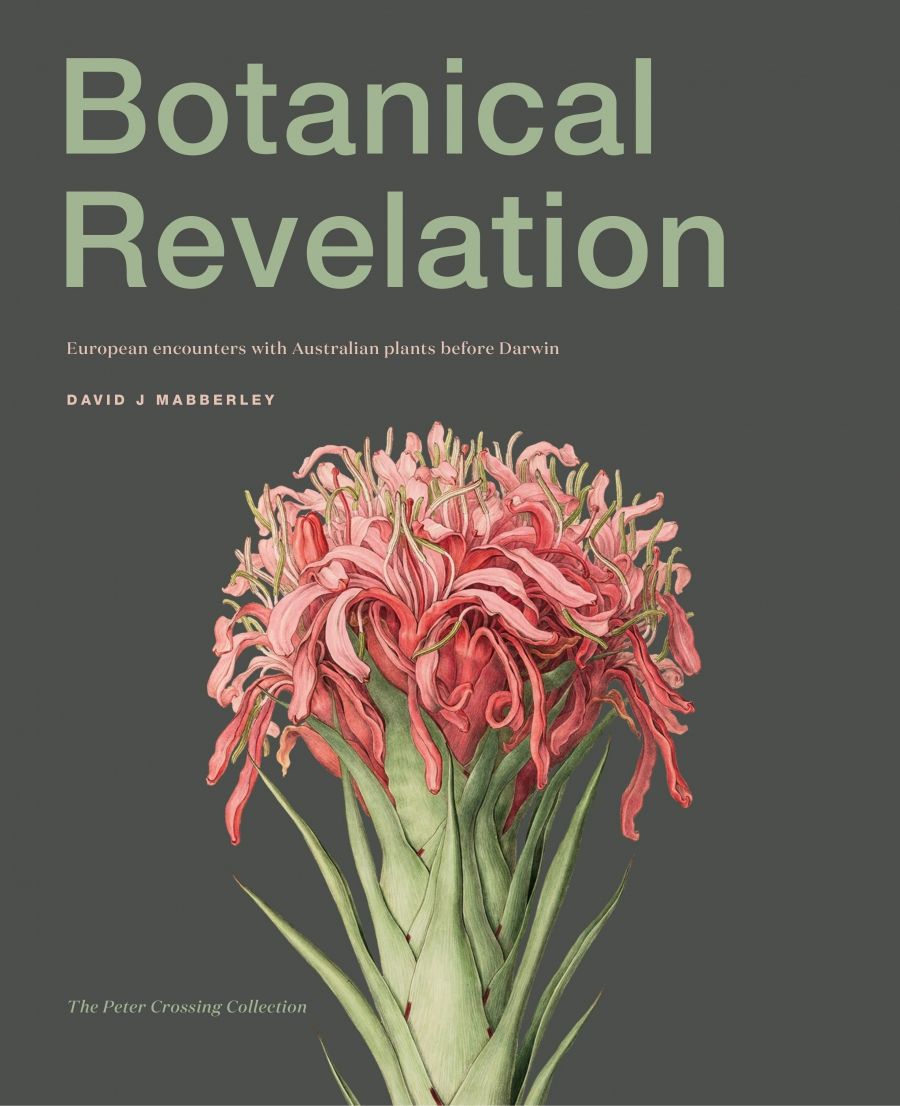

- Book 1 Title: Botanical Revelation

- Book 1 Subtitle: European encounters with Australian plants before Darwin

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $89.99 hb, 372 pp

Botanical Revelation encompasses this early European exploration of Australian botany, from the first collections and descriptions in the seventeenth century to the arrival in Sydney in 1836 of Charles Darwin, who famously noted ‘the extreme uniformity in the character of the vegetation’. The book devotes substantial chapters to the pioneering botanical work of Joseph Banks, James Edward Smith, Jacques-Julien Labillardière, and Robert Brown, featuring the exquisite artwork of illustrators such as Pierre-Joseph Redouté and Ferdinand Bauer as well as many others.

The book is constructed around the antiquarian botanical books and paintings collected by Peter Crossing, who (in conjunction with the State Library of New South Wales of which he is the current Foundation Board chair) has previously produced books and exhibitions on John Lewin, Bauer, and other colonial painters.

Eucalyptus resinifera (red mahogany, Myrtaceae). Henry Cranke Andrews, coloured engraving, in HC Andrews, Botanist’s repository, vol. 6, 1804, tab. 400. Drawn from plant in Lady de Clifford’s garden, Paddington, London, 1804.

Eucalyptus resinifera (red mahogany, Myrtaceae). Henry Cranke Andrews, coloured engraving, in HC Andrews, Botanist’s repository, vol. 6, 1804, tab. 400. Drawn from plant in Lady de Clifford’s garden, Paddington, London, 1804.

With such a rich resource of fine botanical artwork and books to draw on, supplemented with the original specimens from herbariums, Botanical Revelation can be aptly described as a lavish and magnificent hardback production. The text, written by Professor David J. Mabberley, provides a fascinating account of the trials, treasures, and tribulations of Australian botanical research from both shipboard exploration and early colonial work. Mabberley no doubt draws on his considerable experience as a botanist in Europe and Australia and on his previous research into botanical history, particularly relating to Banks, Bauer, and Brown. This expertise is invaluable in untangling the often underestimated complexity of historical botany, particularly in relation to taxonomy, publication, and scientific precedence.

There is no denying that botanists often made uneasy bunkmates on board naval vessels of exploration, even on French vessels explicitly charged with and employed for scientific research by the government. English exploration vessels, confounded with public–private partnerships such as Banks’s, were even more fraught. After Captain Cook’s experiences with Banks’s large retinue on his first voyage, and with the Forsters on his second (who pre-emptively published their account of the voyage, despite promising not to do so), Cook apparently refused to have scientists on his third voyage at all. Similarly, successive French voyages struggled with their civilian scientific staff and, after the Baudin expedition, employed naval pharmacists and physicians to do the work (a strategy that paid off handsomely). For their own part, the botanists frequently complained about the lack of time and resources available for collecting and about the great risks to which their delicate and bulky plant collections (both living and dried) were subjected on board ship. Plant collections and ships seem an inevitably hazardous, if unavoidable, combination, as illustrated by the complete loss of the botanical collections of Lapérouse from Botany Bay in 1788, now known only by a poignant handful of seeds and hardy banksias from the shipwreck of the expedition in Vanikoro, which occurred shortly after leaving Australia.

Nor did the earlier colonial botanists have it much better. While demand for Australian plants was high in Europe, conditions in the colony were not always conducive to art and science, although, as Mabberley points out, horticultural interests ranked high in a colony struggling to produce its own food supply and battling the debilitations of scurvy. Nonetheless pictures, descriptions, and plants alike soon found their way to the opposite side of the world, into English and French gardens, notably in Kew Gardens, the Jardin des Plantes, and the Empress Josephine’s garden at Malmaison, beautifully illustrated by Redouté.

It is difficult to assess the contributions different people have made to our understanding of Australian botany over time. In the most famous example, Banks, often noted as the ‘father of Australian botany’, made substantial Australian collections but failed to publish his accounts in his lifetime, frustrating many of his fellow botanists and minimising his legacy in the scientific literature. Nonetheless, his generosity and support for other botanists, even French rivals, had widespread benefits for the botanical sciences. The name ‘eucalypt’ (named after the characteristic gumnut cap) was coined by Charles-Louis L’Héritier de Brutelle from the specimens he saw while sheltering from an international botanical contretemps in Banks’s library. Similarly, Banks was responsible for ensuring that Labillardière’s collections, which had been seized by the English, were returned to the botanist, rather than the French government, greatly facilitating the publication of one of the first substantial and systematic accounts of Australian botany.

It is impossible to do full justice to the breadth and detail of the entertaining stories of Australian botany scattered through this beautiful and impeccably produced book. Like the plants it represents, Botanical Revelation will be a treasured addition to many collections, and it makes a fine contribution to Australian botanical history.

Comments powered by CComment