- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his lifetime, Alan Rowland Chisholm was widely regarded as an Australian national treasure, and the new biography by Stanley John Scott is compelling evidence that he deserves to remain recognised as one today. This is a book that might have languished as an unpublished typescript, or indeed simply disappeared. Its author died in 2014, having twice withheld it from publication.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Chis

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and work of Alan Rowland Chisholm (1888–1981)

- Book 1 Biblio: Ancora Press, $40 hb, 219 pp

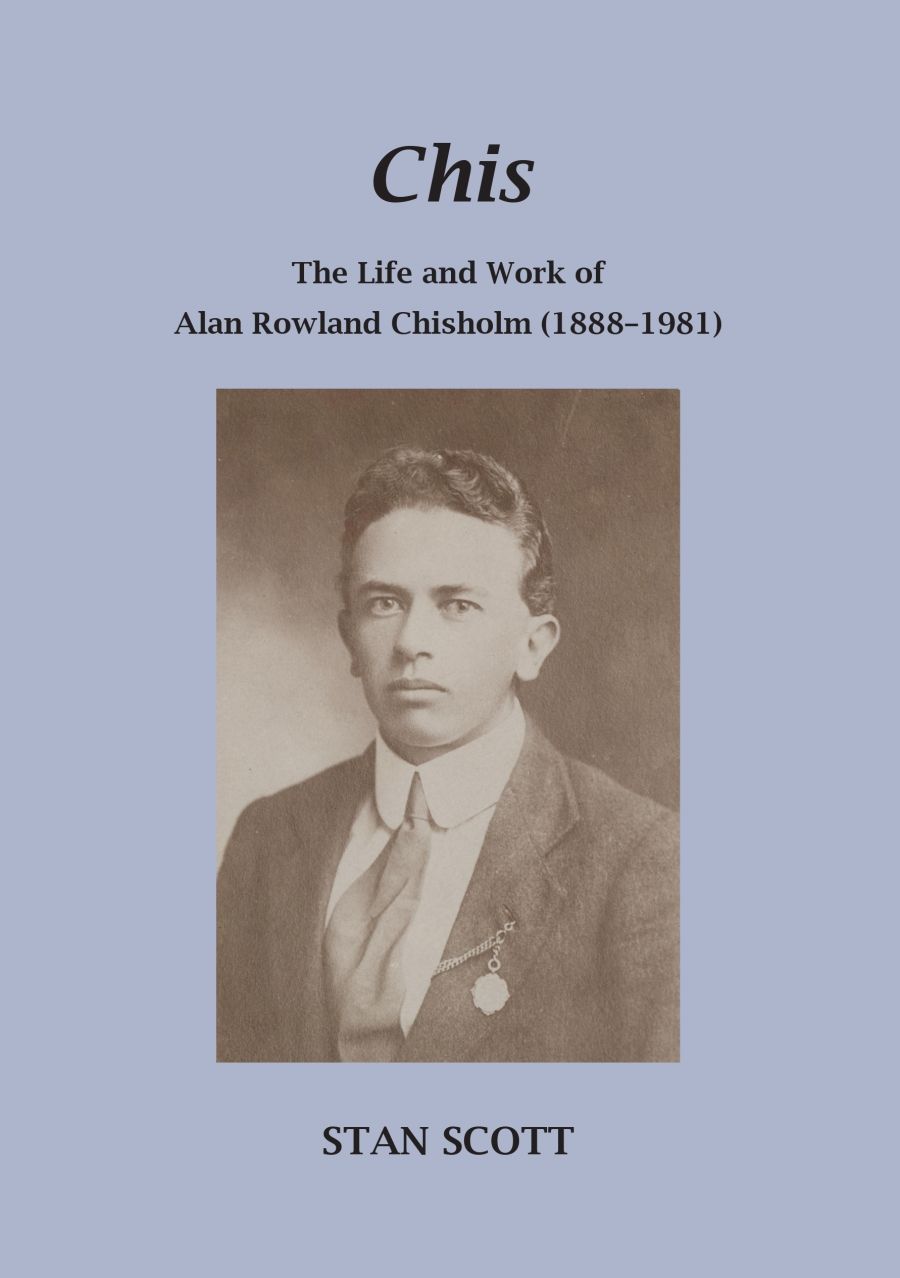

Alan Rowland Chisholm (photograph via The French-Australian Dictionary of Biography)

Alan Rowland Chisholm (photograph via The French-Australian Dictionary of Biography)

Chisholm’s name is legendary in French Studies. During his long tenure at the University of Melbourne (1922–57), where he became foundation Professor of French in 1937, he created a veritable ‘school’: mastery of the language was combined with literary history and textual analysis in a holistic method under-pinned by the conviction that scholarship and critical thought were not mere intellectual exercises but vectors for the highest aspirations of human experience. The impact of this ‘model’ was enduring: it was to be transmitted and developed by various of Chisholm’s students, who became leaders in their field – in Australia, Britain, and the United States. Chisholm’s specialist area of scholarship was French symbolist poetry, and his exegetical work on Mallarmé, in particular, is still – including in France itself – considered as a high-water mark.

That he was the first Australian to be promoted to the rank of Officier in the Legion of Honour is a fitting symbol of Chisholm’s achievements in his chosen profession, but Scott’s book demonstrates that this was only one dimension of a life story that, beyond the academic world, intersects in multiple significant ways with Australia’s broader history and cultural development, providing illuminating insights both into a remarkable individual and the times and society in which he lived. A striking example of this is his service in World War I. While there was nothing overtly heroic in his successive jobs in signals, the wireless corps, and intelligence, as the diminutive Chisholm (he was just above 5’ 2” tall) crawled about among the trenches ensuring vital communications (and eventually contracting sepsis in the foot that would bother him for the rest of his life), his powers of observation and his ability to reflect on what was happening made him very different from stereotypical images of the Aussie Digger. His war diary – which Scott rightly argues deserves a separate publication – is an amazing document in which the immediate experience of the war is depicted alongside his multilingual reflections on his prodigious reading (including Dante in the original) or his learning of new languages (Russian, Spanish) to extend the French, Italian, and German in which he was already fluent. (He would later add Hebrew, Arabic, and Japanese to the mix.)

In the interwar period, Chisholm’s self-avowed conservative bent and anti-communist ideology led him into dangerous waters, at least in his voluminous private correspondence with his old friend Randolph Hughes. David Samuel Bird, in his Nazi Dreamtime (2012), oversteps when he describes Chisholm as a Nazi enthusiast and a ‘hater’; he fails to distinguish adequately between paths that might have been taken and those that actually were. Nonetheless, some of Chisholm’s thinking at this time – which includes undeniable anti-Semitic elements – is a timely reminder of the dangers of seeking simple solutions to the complexities of unstable times and of the neglected historical reality that the Australian experience of the 1930s ideological conflicts often mirrored the better-known temptations of many European societies, including France.

In contrast to the private exchanges with Hughes, when World War II broke out, Chisholm, in addition to his university duties, took to journalism, publishing weekly articles in The Argus for the Allied cause. After France collapsed, he assumed a leadership role in supporting the Free French and Charles de Gaulle. These eloquent and often fiery articles put paid to any idea of Chisholm as a fascist.

Chisholm’s lifelong promotion of Australian literature, through such journals as Meanjin, the Australian Quarterly, and the wider press, led to Robert Menzies naming him to the Commonwealth Literature Board. Some of Chisholm’s own literary ventures remain virtually unassessed: Scott believed that the poetry warranted publication but was unsuccessful in achieving that goal. Today, such things as his efforts to render Mallarmé into Latin verse seem distinctly arcane. There can be little doubt, however, about the value of the memoirs he wrote after retirement: Men Were My Milestones (1958) and The Familiar Presence and Other Reminiscences (1966) are beautifully written and full of wisdom for anyone interested in the development of Australia’s cultural identity.

Scott’s biography, drawn from a rich array of sources and pointing to many more, is one of those books that is likely to stimulate the writing of others. Chisholm’s life opens differently and surprisingly in differing directions. Behind each of his major undertakings – family, war, the history of ideas, literary criticism and creation – one revels in a unique, always intriguing intelligence and a charismatic humanity.

Scott’s life of Chisholm has drawn on a vast array of sources, but Chis may not remain the definitive account of the achievements and significance of Chisholm’s multiple and multi-faceted roles. As the author himself points out, there is still a great deal of unpublished material: diaries, letters, poetry, commentaries. Some readers may be irked by the fact that several important quotations in French are left without translation.

Comments powered by CComment