- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is no great coincidence that many of the best nonsense writers – Edward Lear, Mervyn Peake, Stevie Smith, Dr Seuss, Edward Gorey – were also prolific painters or illustrators. Nonsense poetry often seems like the fertile meeting point of visual and verbal languages, the place where words are stretched to dizzying new limits, used as wild brushstrokes on a canvas of imagination. It is no small irony, as well, that Lear, who virtually invented the genre with poems like ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’, ‘wanted above all not to be loved for his nonsense but to be taken seriously as “Mr Lear the artist”’. In Mr Lear, a formidable biography by Jenny Uglow, he has finally got his wish.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

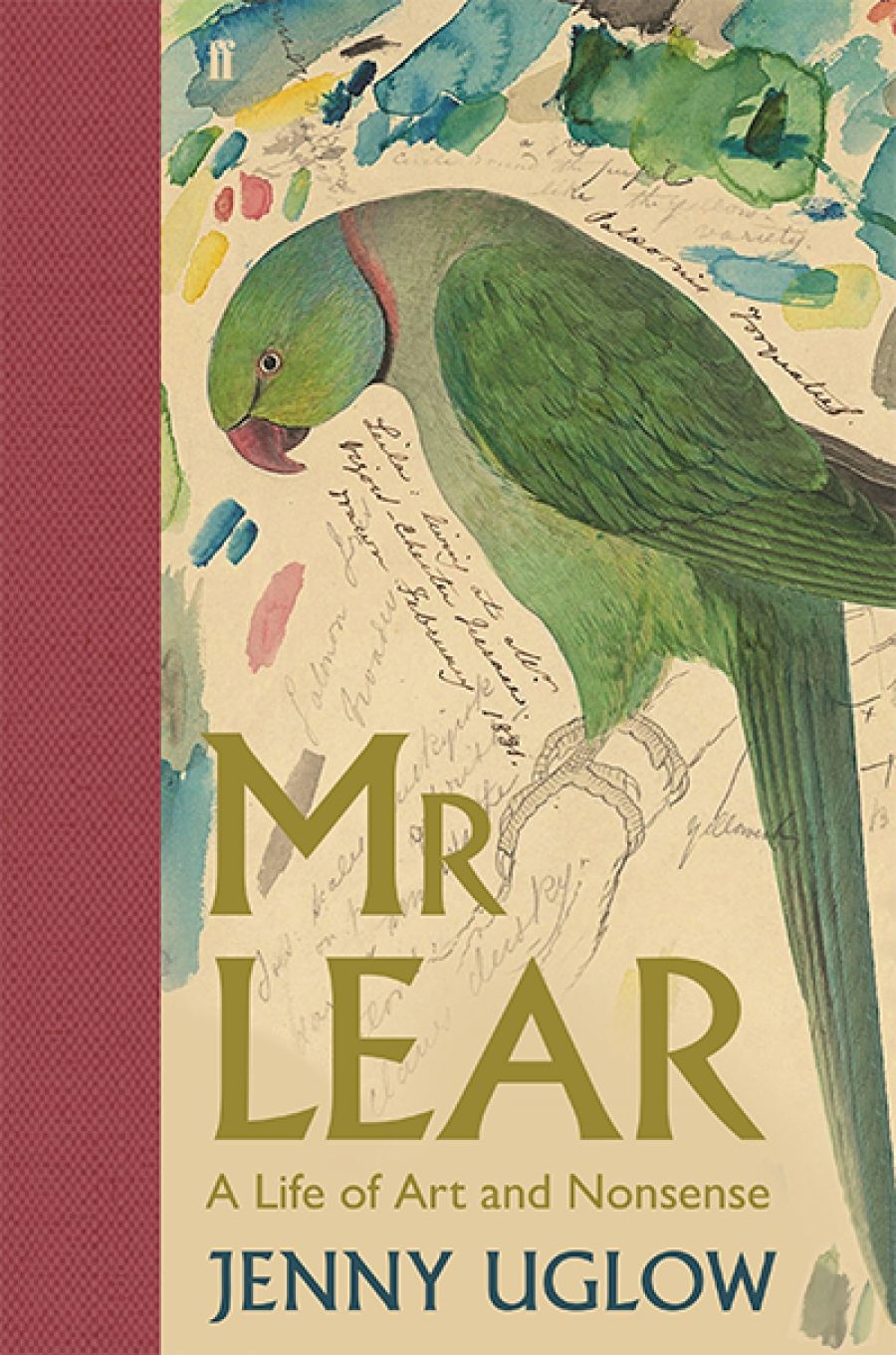

- Book 1 Title: Mr Lear

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life of art and nonsense

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber, $49.99 hb, 560 pp

Edward Lear (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Edward Lear (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Lear was born in 1812 into a middle-class family in Holloway, North London. With more than twenty children, the Lears led a pinched existence, and at the age of four Edward was rejected by his parents and sent away from the home to live with his older sister Ann. The rupture was the first of many difficulties in the young Lear’s life: he also suffered bullying, unspecified (probably sexual) abuse, the need to suppress his homosexuality, and severe epilepsy, the latter of which Uglow describes as ‘the root of the profound loneliness he felt all his life’. There were, however, moments of richness: he formed a close bond with Ann, who helped educate him and read him stories, and by sixteen he had artistic ambitions.

First, he stayed at Knowsley Hall near Liverpool to sketch the birds in the earl of Derby’s extensive menagerie. His ornithological passion yielded some of his most impressive works of art: in 1832 he produced a book of stunning parrot illustrations, every bit as detailed and vivid as John James Audubon’s classic The Birds of America (1827). ‘Birds gave Lear joy all his life,’ Uglow explains; ‘they nest and fly and swim through [his] rhymes’. The exotic names of Knowsley’s many birds and animals were irresistible to Lear, and would inspire later poems such as ‘The Quangle Wangle’s Hat’. It was a great time for naturalists, a time when ‘the world expanded before the eyes of Western savants’, and Lear certainly feasted. Knowsley Hall also sharpened his sense of the overlap between human and animal: ‘the more Lear looked at the smart society set on the one hand, and the animals on the other, the more he seems to have asked, “What does it mean to be human?”’

Lear then travelled to Rome and began painting topographies, the beginning of a peripatetic life that much of the book is devoted to charting. He travelled across Europe (Italy in particular) throughout the 1840s, and later around Palestine, Egypt, and India, and he seems always to have been immersed in beauty. He was even associated with the Pre-Raphaelites briefly, though he found their technique ‘too arduous and fussy’. He inhabited an easy-going world of artists, ‘tolerant of affairs with both sexes’, yet he never grew to accept being gay, despite a friendship with the ‘Uranian’ poet John Addington Symonds, who wrote often on same-sex affairs. During this period he also established a long and complicated friendship with Alfred and Emily Tennyson (documented in depth in the online exhibition Learical Tennysons). The success of his Illustrated Excursions in Italy (1846) led Queen Victoria to ask him for drawing lessons; but in the end his paintings did not sell well, and it is not always easy to reconcile his nonsense writings with these somewhat straightforward landscapes, which went out of fashion with the ascent of photography.

Which brings us to the nonsense. Uglow writes that ‘Lear took up nonsense when tired, or bored, or when it was too dark to paint, images and words swimming up from a realm below reason’. His Book of Nonsense, published in 1846, sold fast. Conceived originally as a ‘semi-private pleasure’, it proved to be the channel through which the latent anarchism that runs through his earlier letters and drawings could finally find expression. Uglow writes that it ‘showed him to be a lyrical poet whose metres were as varied as … Tennyson[’s] and whose moods could embrace yearning sadness as well as wit’. There is also an uneasiness throughout the poems, such as in this limerick:

There was an Old Man of Whitehaven,

Who danced a quadrille with a raven;

But they said – ‘It’s absurd, to encourage this bird!’

So they smashed that Old Man of Whitehaven.

This is a particularly violent poem, but it also displays some of Lear’s main devices and themes: non sequiturs, sharp vicissitudes, that blurry boundary between human and animal. His poems are grounded in everyday sights, sounds, and objects, giving them a sharp satirical edge, while poems like ‘The Scroobious Pip’ may be some of the ultimate expressions of eccentricity. In that poem, other animals clamour to categorise the mysterious ‘Scroobious Pip’, but his only reply is: ‘Flippety chip – Chippety flip – / My only name is the Scroobious Pip.’

It is the appeal to individuality that makes such poems poignant. Lear was the best type of eccentric, someone who through his non-conformism allowed others, at least vicariously, respite from the ceaseless demands of the crowd. He speaks to the inner eccentric in us all, the inner animal who wants nothing more than to turn things upside down and howl in the face of convention. It can be tempting to try to impose meanings on Lear’s poems, to psychoanalyse them, wring sense out of them, but to do so would be to miss the point entirely.

Uglow understands this, and takes a similar approach to his life. Only the gentlest interpretations are offered, and the prose skips along throughout, with its own yearning for this brilliant, tormented man. Mr Lear will surely become the definitive biography of Edward Lear for a generation, and one rather envies the reader with no prior knowledge of the man, who can approach the book and discover a fascinating life, and a whole world so vividly, lovingly evoked.

Comments powered by CComment