- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

From the mainland, the fictional Chesil Island appears to float on the horizon. Perched above its bay, a statue of the Virgin Mary spreads its arms, its robes ‘faded and splintered by salt’. This icon of the miraculous and maternal, crafted from trees and symbolic of the invasion and settlement of Indigenous land, is imposing and worn, revered and neglected.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

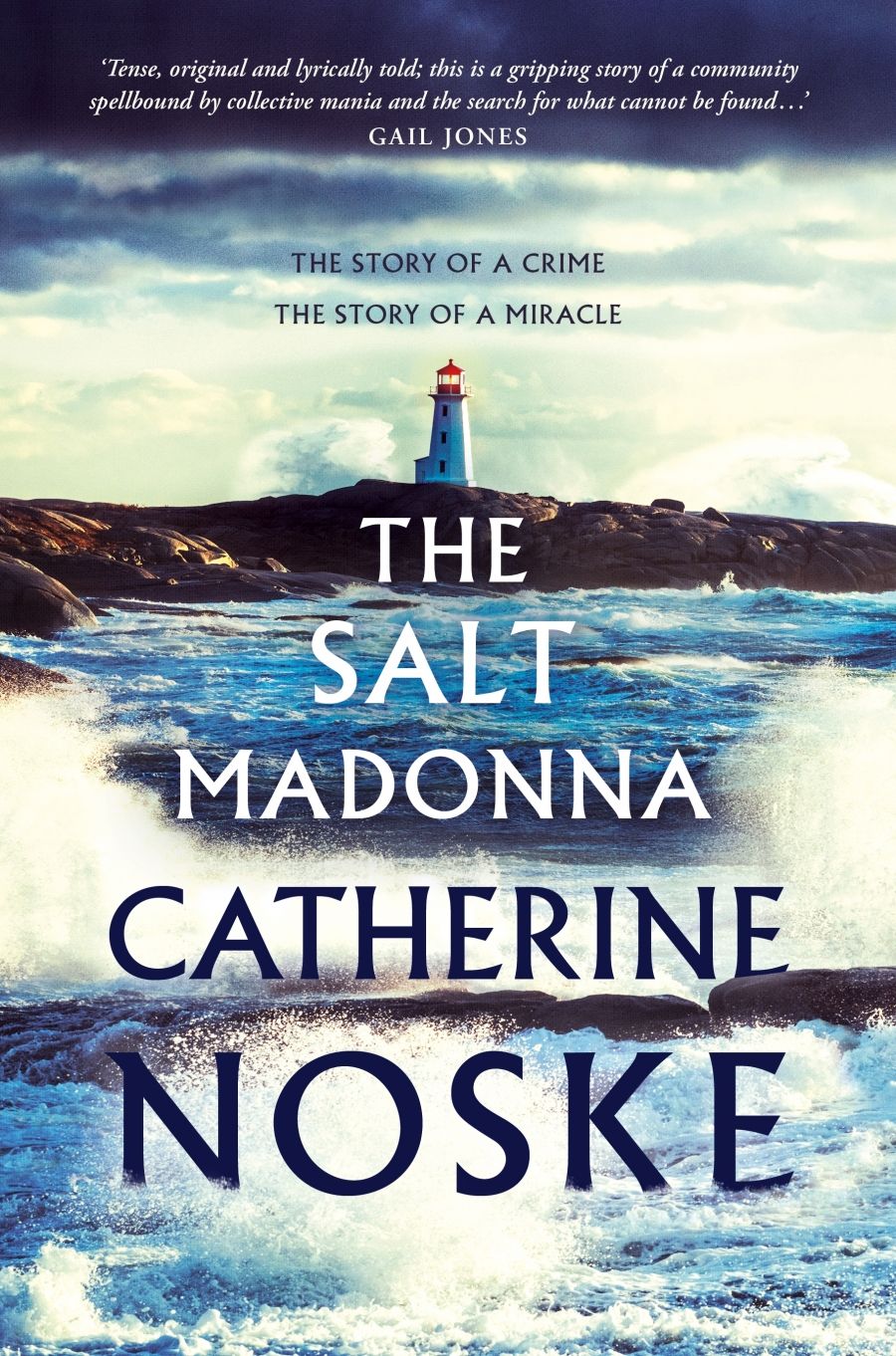

- Book 1 Title: The Salt Madonna

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $32.99 pb, 368 pp

Hannah has returned to spend time with her terminally ill mother and to teach at the local school. One of her students is Mary, though Hannah later admits this isn’t really her name: ‘I am lying about that. I think of her as Mary because that is who she became – the silent one, necessary and yet not really thought of, not really part of it.’

The story is and isn’t Mary’s, and it is and isn’t truthful. She may be the ‘figure, the symbol at the centre of the story’, but Hannah is also unable to know her, or unable to bring herself to imagine her life. At times the shards of Mary’s story blast into Hannah’s perception. Mostly, Mary recedes into imposed silence and the unknowable. One of Noske’s epigraphs is from Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), that novel’s narrator’s apology ‘that there is so much pain in this story’ and that ‘it is in fragments, like a body caught in crossfire or pulled apart by force’.

Noske’s novel is similarly shattered. It is about what Hannah cannot or refuses to know, and the failures of imagination that frame and abet colonial and misogynistic violence. Her first-person narrative begins The Salt Madonna, describing her vision of a girl in the classroom who looks like Mary and the skeletal history of Hannah’s forebear, Mulvey, who ‘dragged pasture out of undergrowth, fouled the water, ringed trees with deep scars and cleared them’ to produce the familial line.

Catherine Noske (photograph via University of Western Australia)

Catherine Noske (photograph via University of Western Australia)

Among the slivers of uncertain and haunted narrative the novel collects, the story of Mulvey lurks. His diaries, which Hannah reads, describes the invasion and settlement of Chesil Island. Indigenous people are ‘not real to him’, numbered rather than named, imagined as ‘some malevolent manifestation of the place itself’. While some of his account celebrates the island’s natural beauty, he also details the atrocities that he perpetrates with scant awareness of the horror and burden of his actions.

This history abuts a present in which the ways women are imagined and treated are a central concern. The local priest is a recent widower, but his late wife is alongside him in more powerful ways than his circling parishioners with their needy generosity and foil-covered casseroles. At one stage, he throws these gifts onto the back lawn, their ‘strange bounty’ defrosting in the sun as he fasts his way into vertiginous communion with his wife.

As he recedes into these rituals, the veils between history and the present thin. His wife merges with the statuette of the Virgin Mary on his windowsill, ‘a little dream, a little dream-puffed memory’. Harmless, except that in this dreamy state, a crime might masquerade as a miracle, a violated child might look like a visitation, ‘sublime, haloed and pure’, and a community’s deceit and fear might morph into fervent delusion.

Noske, a writer and academic who edits Westerly, offers a sharp examination of faith and lies. The novel’s form brilliantly expresses this, splicing a fast-paced mystery with intense and lyrical contemplation of place, memory, and history. Its shifting between memory and the present, first- and third-person narrative, and action and lyric conveys a powerful sense of the provisional nature of storytelling and the ethically dubious nature of narrating someone else’s story.

Salt is preservative as well as corrosive – capable of healing and injuring. When it crusts the statue, a luminous miracle might eclipse dark truth. As Hannah’s own past trauma surfaces to obscure her vision, the community is drawn as though by a sea current into a ‘sort of shared hallucination, communal and projected’. A mythic story can blanket crimes that people would rather not acknowledge, and the possibilities of faith as an alternative to science lure the islanders as they face environmental decline and fear.

‘The Virgin was a mirror’, Hannah thinks: ‘we all saw in her what we wanted to’. When Hannah finds herself unable to imagine Mary’s life, she thinks of the girl herself as a mirror, in which ‘it is myself I am struggling to see’. Hannah tries to intervene on Mary’s behalf, but balks at the gate of the girl’s home. When she tries and fails to make another important visit, she wonders how often ‘can one person stop at a gateway, doing nothing?’

This question pulses through the novel. We might witness something or instead reimagine it in the image of comfortable delusion. Faith might sustain or corrode. Women’s stories, including those of Indigenous women, might be shunted to extremes of adulation and obloquy. The Salt Madonna, compared in its media release with Charlotte Wood’s formidable The Natural Way of Things (2015), melds the fabulous and allegorical as it searches questions of witness, violence, and hope.

Comments powered by CComment