- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Leah Purcell has described how her lifelong fascination with Henry Lawson’s iconic 1892 short story provided her with abundant creative ammunition. Her mother read her the story when she was five; it held a special place for them both. ‘I’d say the famous last line: “Ma, I won’t never go drovin ... she’d tear up”.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

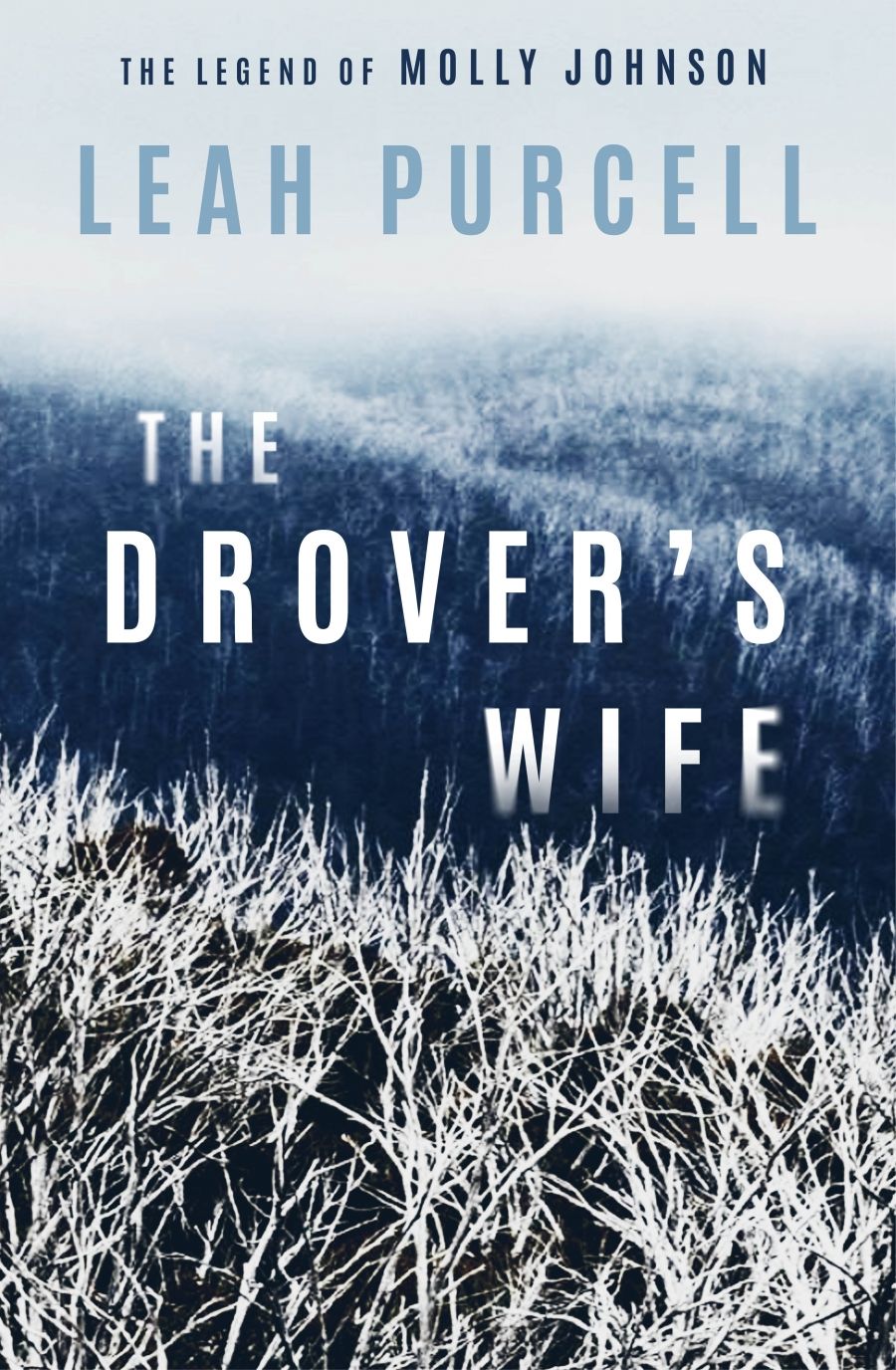

- Book 1 Title: The Drover’s Wife

- Book 1 Subtitle: The legend of Molly Johnson

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $32.99 pb, 288 pp

The story has been adapted by many Australian writers, including Frank Moorhouse, Barbara Baynton, and Ryan O’Neill. Purcell is the first Aboriginal writer to tackle it. The medium of choice here is her first novel, after a critically acclaimed play that premièred at Belvoir St Theatre in 2016. A film adaption is in post-production, and a television series is on the cards.

Purcell resolved to tell her version of ‘The Drover’s Wife’ while on location in the Snowy Mountains making Ray Lawrence’s film Jindabyne (2006). Purcell’s descriptions of this place in her novel are heightened by a striking cover design featuring a photograph by Murray Fredericks. We read about this country and its snow gums and inevitably think of the recent catastrophic fires.

Leah Purcell in the 2016 Belvoir St Theatre production of The Drover's Wife (photograph by Brett Boardman via Flickr/Belvoir St Theatre).

Leah Purcell in the 2016 Belvoir St Theatre production of The Drover's Wife (photograph by Brett Boardman via Flickr/Belvoir St Theatre).

Purcell’s novel examines gender politics through its central characters. Molly encounters Yadaka at a time when both need each other. Yadaka is on the run from the authorities, and Molly is in labour. Through Molly and Yadaka, The Drover’s Wife contrasts the struggles of white women with those of Aboriginal men during colonial times. Even when Molly cuts off Yadaka’s collar – symbol of property – they are not of equal status. The white authorities will not be happy until Yadaka is killed and Molly returns to the domestic sphere.

In the nineteenth century, the new colony was a ‘man’s world’, though white women were not mere victims. Historian Marilyn Lake has written of white women’s double identity as ‘both colonising and colonised’. White women participated in and benefited from colonial violence through the theft and mistreatment of land, the killing of Aboriginal people, and the separation of families. ‘White women civilised while white men brutalised,’ Aileen Moreton-Robinson writes in Talkin’ Up To the White Woman: Indigenous women and feminism (2000). Purcell’s writing of this becomes more complex at the novel’s twist (which I won’t spoil).

There are many Aboriginal characters in Purcell’s novel, in contrast to their minor roles in Lawson’s story. The local Ngarigo have an active presence, both as spirits and among the living. The bush in The Drover’s Wife is a place of spirituality and healing, to be understood and lived with rather than feared and fought against.

Molly demonstrates what is seen through a Eurocentric contemporary reading as masculine qualities; at seven she could ‘kill, skin, gut, cut and cook’ a roo. She uses native plants for medicine or food. Her breast milk draws out a lurking snake, which she kills. (Yes, you did read that sentence correctly.) Molly is closest to her eldest son, Danny. Sensitive and thoughtful, he possesses a combination of feminine and masculine energies. Unlike the other children, he seems to intuit his mother’s secrets.

The book’s prelude foreshadows a friendship between Danny and Louisa Clintoff. Louise, a newspaper proprietor, has encouraged Danny to write poetry by Louisa. Henry Lawson’s writer, publisher, and suffragist mother, Louisa, began a journal called The Dawn. Louisa published and encouraged Lawson’s first writing. She also founded The Dawn Club, which became the hub of the suffrage movement in Sydney. Although Purcell honours her legacy, the character feels representative of a movement and is one-dimensional in comparison to Molly, Yadaka, and Danny.

Yadaka could be the embodiment of the man with his head held high in Lawson’s story. He’s troubled and pained but not ashamed of who he is. He’s from Guugu Yimithirr country – land of rainforest and coloured sands, his mother’s country – and trying to get back there. Purcell explores her own inherited stories through Yadaka, who is based on her great-grandfather, another Queenslander. Like Yadaka, he was made to tour South Africa as a circus performer.

Like the legendary Uncle Archie Roach, who released his memoir Tell Me Why in 2019, Purcell is an impressive all-rounder. I saw her rousing performance in her stage version, which won several major awards. As an aspiring theatre-maker, I read the outstanding script. I have been a fan of Purcell’s drama since the strong, lean writing that emerged from Box the Pony (1997).

As a novel, The Drover’s Wife can drag. Point of view changes abruptly from third to first. It feels as though Purcell is using tools straight out of cinema. The numerous ‘angles’ can sometimes create lag. If anything, this work suffers from coming after a successful play. Purcell mentions that material from both have been borrowed for this novel, permitting the addition of back-stories and characterisation. The set-up in Purcell’s prose leaves us craving action. Ultimately, we are rewarded. After the reveal, the book blisters at great speed to its well-executed ending.

The extent to which Lawson’s story has fuelled Purcell’s work is evident in the high level of detail faithfully transferred from the original. Purcell has written herself and her mother into Molly Johnson’s story because they recognise themselves in it. This layered adaptation reminds me how retellings by those who can offer a different perspective can unsettle the status quo. More appropriations and contestations of ‘the classics’ by First Nations writers, please.

Comments powered by CComment