- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Anne Enright has never been able to resist the tidal pull of mothers; her novels are animated by complex, ambivalent maternal presences, women rendered on the page with duelling measures of hatred and hunger, empathy and censure. There is the mercurial tyrant Rosaleen Madigan of The Green Road (2015), ‘a woman who did nothing and expected everything’. There is the hapless, hazy Maureen Hegarty of the Booker Prize-winning The Gathering (2007), erased by her endless pregnancies and too many children; ‘a piece of benign human meat, sitting in a room’.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

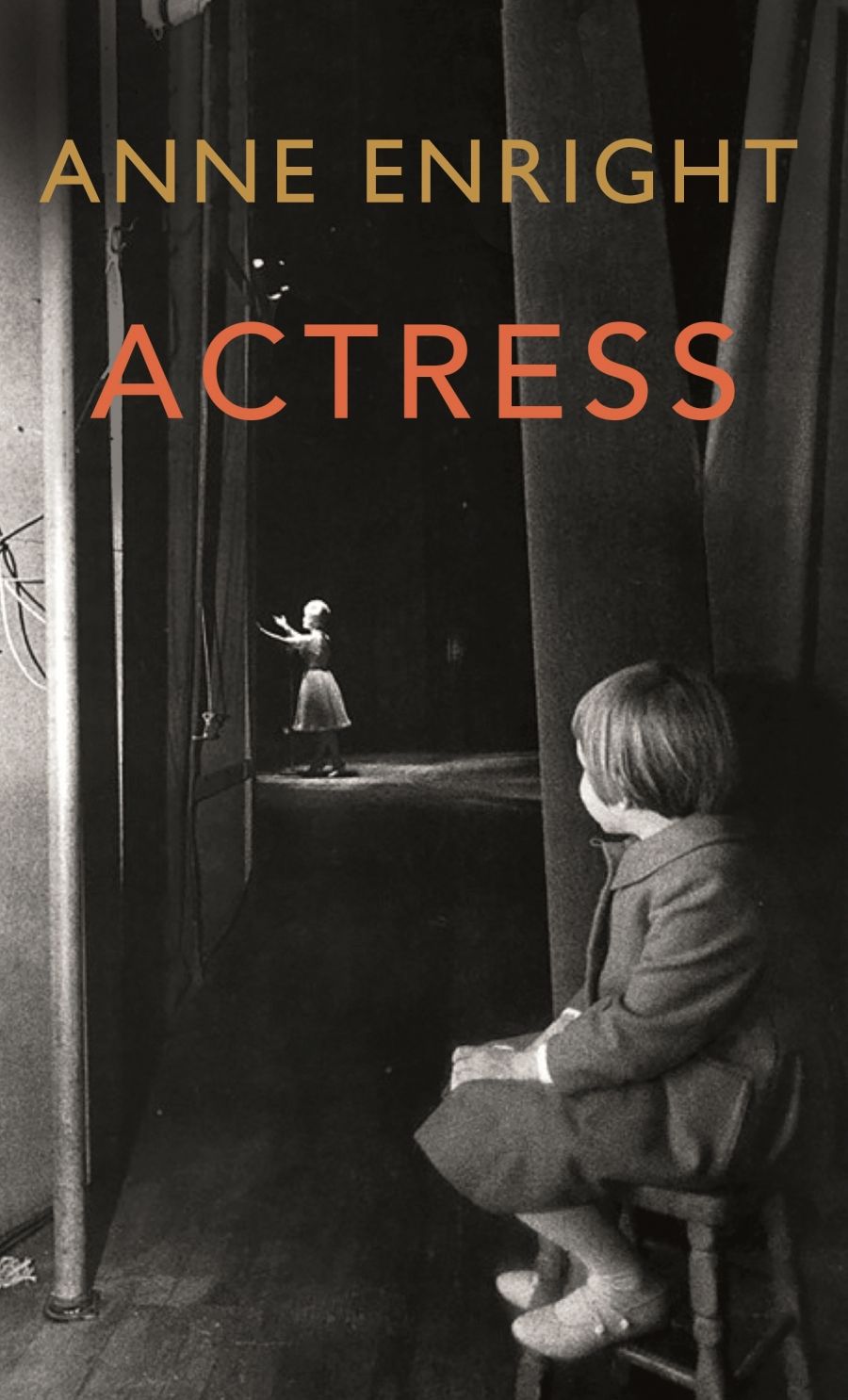

- Book 1 Title: Actress

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $29.99 pb, 264 pp

‘We pity our mothers,’ Enright says in The Gathering, ‘what they had to put up with in bed or in the kitchen, and we hate them or we worship them, but we always cry for them.’ This elegiac sense pervades Enright’s novel Actress, which is also a fraught hymn to a complicated mother, but in this new work something has gone awry. There is a strange slackening of vitality and a failure to fully penetrate the hidden recesses of individual lives that results in an oddly unsatisfying novel, though one that is not without its quietly luminous moments.

One of the difficulties of Actress, which is cast as a daughter’s diligently rendered posthumous account of her famous mother’s life, is that it inhabits almost entirely what James Wood calls the ‘pressureless zones of retrospect’. Like The Gathering, this novel is concerned with the reanimation of one painfully evanescent life through reflection and reimagining. Unlike that masterful earlier novel, Actress feels hobbled by the dutiful restraint of the biographer.

Norah FitzMaurice, daughter of the long-dead Irish star Katherine O’Dell, recounts the story of her mother’s life and career in one long sweep of narrative. Darling of the Irish stage and screen, Katherine was the beautiful daughter of strolling players, making her stage début at the age of ten. A role as a young Irish nun in a film called Mulligan’s Holy War catapults her to fame and fortune, and her legion fans later delight in her appearance in an iconic television advertisement for Irish butter. Subject to all the usual insecurities of the ageing beauty with diminishing prospects, Katherine’s life is clouded by scandal after she somewhat inexplicably shoots a film producer in the foot. Then we see her addled in an asylum, paranoid and speaking gibberish, her insanity rattling away ‘like the lid of a boiling pot’. Tethered as it is to the past, the only forward momentum that the novel has is Norah’s attempt to resolve certain questions about her mother. In the end, these questions are not urgent enough to sustain the story.

Enright herself has forcefully eschewed the antic, performative nature of plot, calling it an ‘externalised mechanism of revelation’, privileging instead the intimacy of story, which she conceptualises as ‘telling it into someone’s ear’. Her privileging of style places her in a fine tradition; it was Flaubert, after all, who wrote that the most beautiful novels are those with the least matter, that the subject of art is irrelevant and literary style itself the absolute way of seeing things. But abandoning the machinations of narrative relies upon the incantatory power of voice. In Actress, the monologic narration that has served Enright so brilliantly in her other novels falters.

The sedulously rendered account of Katherine O’Dell’s life has a static quality, and for all that Norah tells us about her mother’s commanding presence, she never comes fully into focus. Instead, her attempts to explain her mother frequently devitalise and reduce her. Norah informs us: ‘And Katherine O’Dell was an artist. She was all about sincerity, courage, self-sacrifice. That was the whole point. With each iteration or draft or performance she gave it everything she had. Everything!!’ There is something anodyne and clotted about these kind of summations, something unworthy of Enright.

Despite its missteps, Actress still has its flashes of brilliance. The crystalline prose of Enright’s earlier novels is frequently on display, as is her inimitable turn of phrase and her mordant humour. Watching her husband sleeping, Norah reflects on ‘the disaster of the body when it does not know itself, or realise that someone else is there’. A priest looks like ‘a pocket version of God’. A poet sounds testy when reading his work aloud, ‘as though obliged to expose his yearning to the crowd’. Enright has always been a virtuoso when it comes to writing about sex; its enigmatic singularity and mechanistic sameness, its violence and tenderness coexisting in equal portion. Of Norah’s disbelieving joy in her first sexual encounter, she writes: ‘This first surprise was quickly lost in a larger astonishment, that such a thing could happen inside you − a place I had not properly considered − it felt like he was going up into my head, right into my mind.’ Later, she writes about an exploitative encounter with a man who is ‘so inward, so inert in his pleasure’ that ‘it did not feel like he was fucking me, he was just trying to find and catch his own pleasure’.

It is insights like these that makes us yearn for more of Norah’s interior life than Enright allows us. But just as Norah has finally seized hold of our imagination, the curtain falls and she is gone. We mourn the slenderness of her presence, just as we mourn Enright’s failure to deliver a fresh and fully imagined fiction when we had greedily expected so much more.

Comments powered by CComment