- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse has revealed systemic mistreatment of vulnerable children over decades. Though these crimes have not been the exclusive province of the Catholic Church, its education system has brought more children into intimate care by religious orders, and even those never abused have observed the tics of brutality in some of their teachers and mentors. In a note at the end of his new novel, In Whom We Trust, John Clanchy mentions James Joyce’s hell-fire sermon in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) and the recurrence of these ‘tropes of terror’ in the rhetoric he heard as a Catholic schoolboy in 1960s Melbourne. The system has long-standing practices of psychological control.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

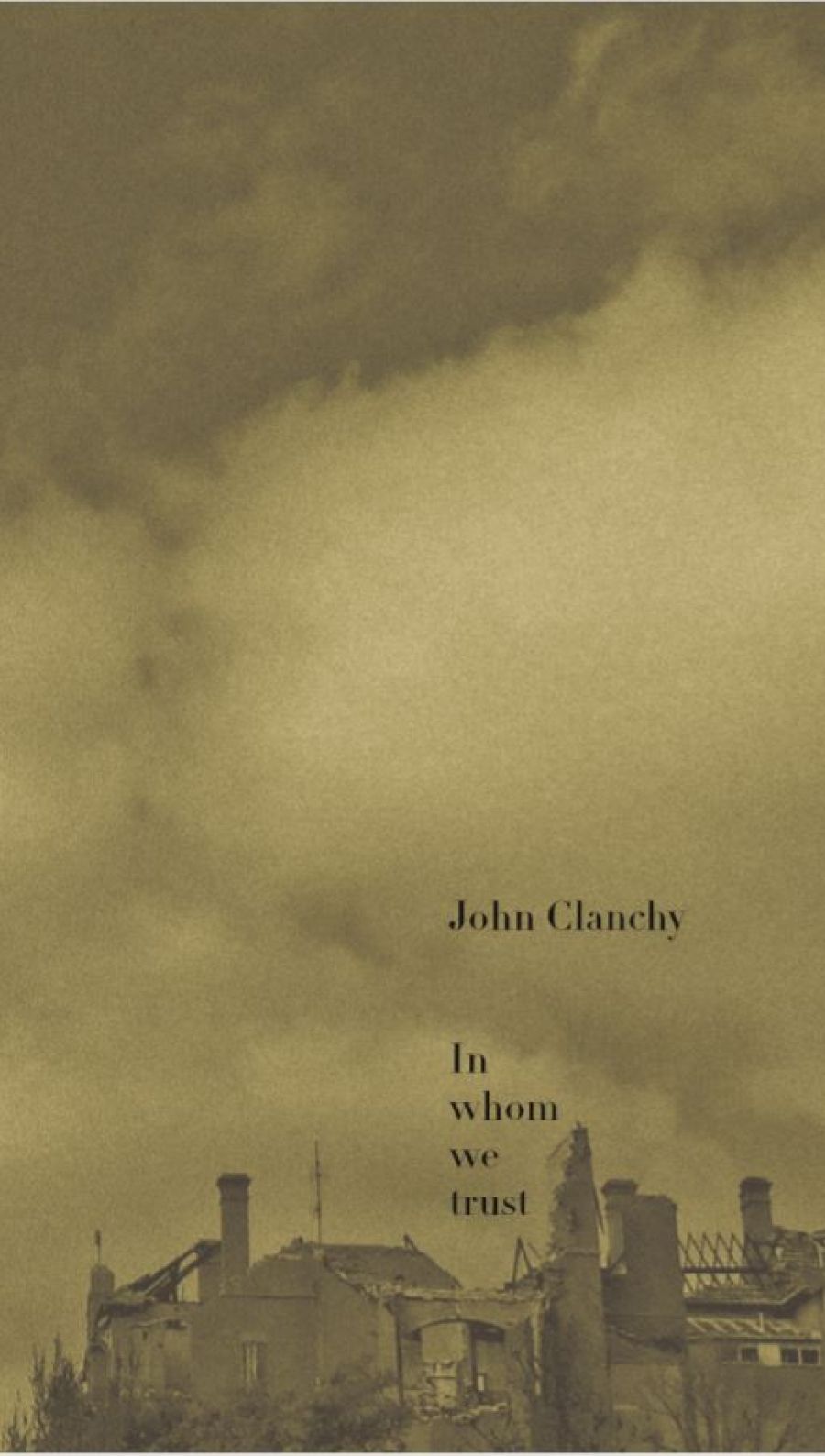

- Book 1 Title: In Whom We Trust

- Book 1 Biblio: Finlay Lloyd, $28 pb, 246 pp, 9780994516558

Rather than address child abuse as a contemporary problem, In Whom We Trust focuses on an Irish priest, Father Pearse, who is working out his last years as the ‘permanent temporary’ parish priest in Gippsland during World War I. It dramatises the arrival at his presbytery of an adolescent boy, a runaway from St Barnabas’s Orphanage in St Kilda, and the boy’s insistence that Pearse take action against the main perpetrator of sadistic sexual abuse in the orphanage. Their confrontation initiates Pearse’s memories of his own boyhood in Ireland and the series of personal failures that led to his vocation. He has been a mediocre priest, never speaking out of turn or seeking preferment. His duties as chaplain to the orphanage include hearing the confessions of both the children and the Brothers who run it. In this role, he has been privy to the children’s ‘sins’ of impurity and has absolved the Brothers who are practised in the craft of evasion. Nevertheless, the children see him as the only outsider with a sense of decency who might help them.

Thomas Stuart, an orphan from the streets of London, has a natural intelligence and nothing to lose by defying the system. He has enlisted in another institution, the army, as an avenue of escape, but he wants to protect the children left behind. He knows that Pearse has evidence of abuse in the form of a diary, written by the teenage Molly Preston, and insists that it be read and presented to church authorities. Through this diary, Clanchy conveys to us the detail of the abuse of Molly and Thomas. Molly’s honesty and simplicity of expression allows Brother Stanislaus’s cruelty to be presented with tact; it focuses on the after-effects of abuse and her concerns to protect Thomas, rather than the horrors of sexual exploitation. Molly, it suggests, has been abused by so many people for so long that she has developed a stoicism and a degree of self-blame. She is kept strong, though, by access to the diary as a form of resistance.

Thomas, on the other hand, has learnt the sophistry of Church doctrine. He argues with Father Pearse about the fine points of confessional confidentiality and the nature of sins of omission, pushing the priest to recognise his moral responsibility to cause trouble. When Pearse finally visits the bishop to ask for Brother Stanislaus’s removal, he must be ready to counter these defensive rationalisations. Disturbingly, these arguments will be familiar to anyone following the Church’s current justifications for its protection of the criminals in its midst. The privacy of the confessional is elevated above the rights of victims. Little has changed.

John Clanchy (photograph via Facebook)

John Clanchy (photograph via Facebook)

By placing this story in the past, Clanchy resists any direct comment on the current situation, though its relevance to the present must be obvious to readers. In fact, his depiction of Father Pearse’s crisis a hundred years ago appears rather optimistic as he invites us to hope, with Thomas, for justice. Father Pearse and his bishop are men seeking a quiet life, rather than monsters. Yet the relationship between the secular clergy and religious orders was, and seems to be still, a matter of difficult politics. Within the system, even good men find it difficult to act.

Clanchy has been publishing sensitive and finely structured short stories for decades. In this novel, his focus on a small cast of characters in a circumscribed place and time creates a sense of confinement, whether within the walls of the orphanage or the system of the Church. It shifts effortlessly between Father Pearse’s meditations, the drama of his confrontations with Thomas and the bishop, and Clanchy’s restrained and engaging creation of Molly’s diary. There is a quiet discipline to this art that resists the potentially sensational nature of its subject.

Setting the novel in a time of war provides another level of challenge to Thomas and his fellow orphans and a further restraint on Father Pearse’s desire to return to Ireland. It provides the kind of universal threat that might have overwhelmed any concern for the rights of children. Yet I wondered at the lack of any reference to the accusations of the Irish Catholic disloyalty in the early years of the war, or to the Easter Rising in Dublin. I kept expecting Daniel Mannix to appear. These obvious absences reinforce the sense that the novel is as much about current circumstances as historical conditions.

Comments powered by CComment