- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australian nature writing has come a long way in recent years. Not only do we have an abundance of contemporary nature writers, but we are also rediscovering the ones we have forgotten. The neglect of Australia’s nature writing history, with its contributions to science, literature, and conservation, is happily being redressed with recent biographies of Jean Galbraith, Rica Erickson, Edith Coleman, and now a new biography of Alec Chisholm.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Idling in Green Places

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life of Alec Chisholm

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $49.95 pb, 285 pp, 9781925801996

Chisholm’s early childhood in rural Victoria reveals no great affinity for nature, beyond the usual pursuits of shooting birds and collecting eggs. It does, however, betray a predilection for his own company and some difficulty getting on with others, suggesting that his legendary curmudgeonliness was not just an acquisition of old age. Journalism seems to have been the catalyst and driver of Chisholm’s career. Like E.J. Banfield and Donald Macdonald, he was employed by newspapers and spared the need to work freelance unlike most female nature writers of the time. Like his contemporaries, Chisholm was staunchly nationalistic in his patriotic appreciation for Australian nature, but he lacked the militaristic and masculinist overtones of some others.

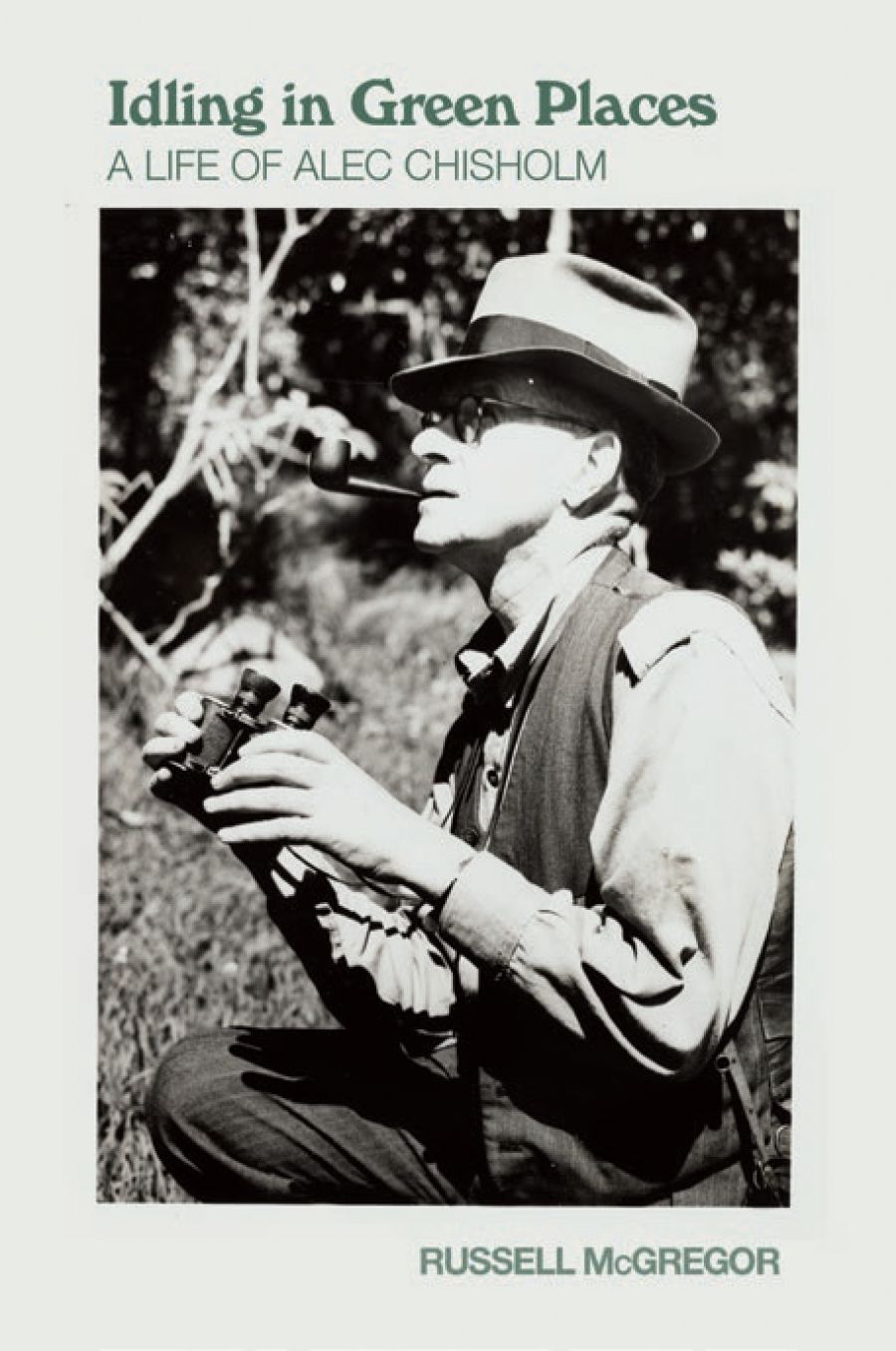

Alec Chisholm (photograph via the NSW State Library)

Alec Chisholm (photograph via the NSW State Library)

McGregor describes Chisholm’s ongoing role in various ornithology and field naturalist clubs. His conservation work ranged from lobbying for Queensland’s Animals and Birds Act 1921 to being a figurehead for conservation in the 1950 and 1960s. But it was his popular nature writing, in newspapers, natural history journals, and books, that had the most impact, alongside his promotion of nature study in schools. Such influence can be difficult to measure, but McGregor presents enthusiastic letters from Chisholm’s readers, testifying to his inspiration and long-term impact.

It is rather a shame that not much of Chisholm’s writing appears in this book. As a historian, McGregor seems uncomfortable with Chisholm’s ‘lavish style’ and regards its whimsical, literary, anthropomorphic, and poetic features as faults rather than popular narrative devices of the time that delighted his readers. The charm of Chisholm’s writing is apparent whenever it does appear, such as in this passage about the ‘vagrant Hawkesbury sandstone’ of Sydney:

I love its brooding solemnity and the friendly roughness of its surface, whether festooned with lichens and moss and ferns and orchids or merely stained by the centuries: I love its shadowed cliffs and pillars and turrets, its fantastic caves and niches in which the brilliant lyre-birds nest, its tumbled masses upon which the Old People have left their curious carvings for the white successors to wonder at, and its reckless hillsides where the smooth-barked angophora trees, decorative but aloof, cling on and about the rocks and sometimes split great slabs of sandstone asunder in their growing. And the gleam that lights the great face of the sandstone after rain, as it has lit that austere face for a thousand thousand years; the furtive trickling of water between ferns and moss into quiet pools; and the merry adventuring as the creek gathers volume and falls over rocks and cliffs – how these things invite the soul.

A little dated, perhaps, but it makes me want to read more of Chisholm’s own words.

Not everyone’s life story makes for a good story or has a great mystery to uncover. Biographies, particularly of scientists and writers, are challenging. The recent J.R.R. Tolkien biopic, for example, was widely critiqued for being just a bit too ordinary, as if audiences were disappointed that such an influential and imaginative writer could be so mundane in real life. Focusing on the person instead of their work sometimes detracts from the very thing that makes them appealing. Chisholm is interesting because of his love of nature and his ability to communicate that fascination. He was clearly an inspiring public speaker and a wonderful companion on a bushwalk, but perhaps not someone you’d want to make small talk with. I kept hoping the story would focus more on what Chisholm was doing and what he was looking at (the major conservation battles and the wildlife) rather than his personality and daily activities..

Nonetheless, this is a worthy biography of a man who deserves to be remembered for his important work. The book is an easy read, well structured with thorough referencing and a useful index. It will be a valuable resource in biology, history and philosophy of science, and literary studies. While the price and minimal production values might be off-putting, it is likely to be popular among bird enthusiasts and those interested in natural history more broadly. More importantly though, this book is a useful contribution to our literature on Australian nature writers, on the origins of our conservation movement, and on the role nature plays in our efforts to define what it means to be Australian.

Comments powered by CComment