- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Japan

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Meredith McKinney, our pre-eminent translator of Japanese classics – among them Sei Shōnagon’s The Pillow Book, the poetry of Saigyō Hōshi, the memoirs Essays in Idleness by Yoshida Kenkō, and Kamo no Chōmei’s Hōjōki (Record of the Ten Foot Square Hut) – has delivered another marvel of absorbing, elegant scholarship. Travels with a Writing Brush crosses the country of old Japan, from north to south and from east to west, and is a quintessential travel book. It goes to places, and shows them – except that the latter is not quite true; you would not go to this book to see things objectively so much as to cue to them imaginatively.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

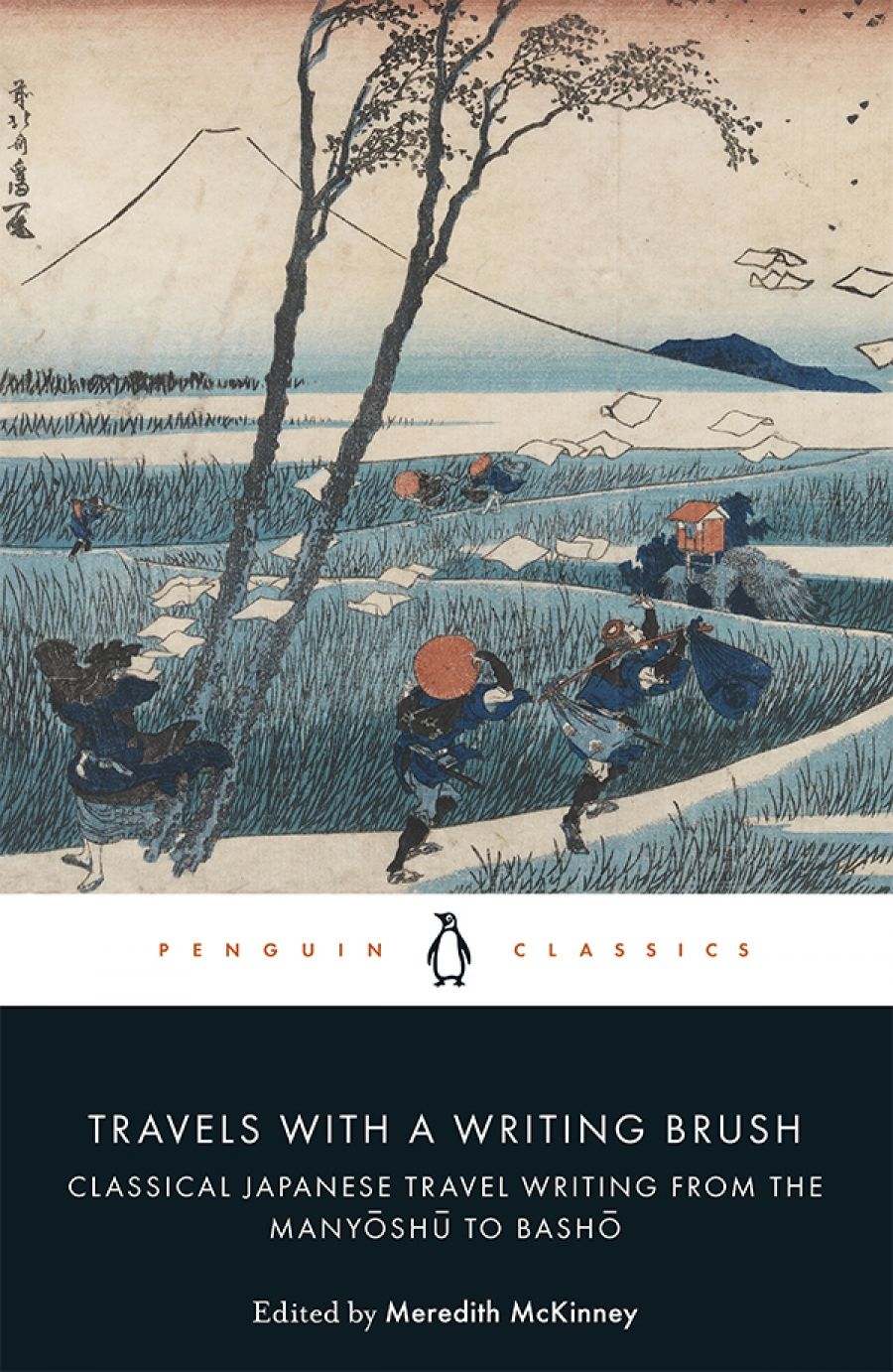

- Book 1 Title: Travels with a Writing Brush

- Book 1 Subtitle: Classical Japanese travel writing from the Manyōshū to Bashō

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $24.99 pb, 382 pp, 9780241310878

Sketching the matter like this might remind us of the songlines in the original Australian landscape. At the Strehlow Research Centre in Alice Springs, I have seen a digital map lit by the sacred sites that belonged to the origin and passage of ancient songs – a sight that lifted the heart as, I imagine, their utamakura could do for Japanese travellers. This is the marvel of McKinney’s anthology. Her labour of love, arising as it does from her years of scholarly work in classical Japanese, immerses us in a great tradition – a thought and feeling stream – of refined literary travel.

The first poem here comes from one of the oldest anthologies, the Man’yōshū, which was assembled in the eighth century with 4,500 poems.

As we go rowing

around the cape of Minume

hard by the island

longing for Yamato

cranes flock and cry

What could be simpler, or sharper? The preceding prose-poem fills out the context: ‘A sea god must be … a god divinely powerful ... to place in its centre ...’, then rushes forward in McKinney’s hand, bird cries and sea spray caught up in it all. The poem is a nice reminder of the dangers of travel, whether by sea or land.

Of course, the Man’yōshū was not only loaded with travel poems in a resonant, sometimes divine landscape. Among other things it was replete with love poems that flourished in Japanese poetry through the ages. Indeed, travel enlarged the heart’s yearning.

So many nights

spent on the journey

how I yearn now

thinking how long since my hands

loosened her crimson undersash

Portrait of Bashō by Hokusai, created in the late eighteenth century (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Portrait of Bashō by Hokusai, created in the late eighteenth century (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Travels with a Writing Brush becomes an absolutely uncompromising introduction to the Japanese sensibility from before the time of The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu when the capital was in eleventh-century Kyoto (and the world’s first novel was written by a woman), to the artful making of Matsuo Bashō’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North in 1689, when Bashō set off from the new capital in Tokyo. In those centuries the nature of travel changed, as did poetic forms and the social demands upon poets and their audiences. Not the least of McKinney’s achievements is her tracking of developments that sustained the core sensibility of aware (poignancy) at their heart.

Out of The Tales of Ise, we get the typical yearning of the traveller leaving the capital – ‘Travelled distances / reach back and back to home. / Yearning for all I love / I watch with envy / the returning waves.’ In the following section, self-consciousness is extended by extracts from The Tosa Diary, where the diarist feels free to adopt the persona of a woman, announcing herself in his first line: ‘I have heard that men write diaries, but a woman will try her hand at one here.’ It is McKinney’s moment to remind us that The Tosa Diary continued the diary writings of the Heian court with its ‘wit, language play and the pose of what is known as elegant confusion, a lightness of touch that offsets the weightier poems of sorrow and longing’.

Another tonal shift is registered by Retired Emperor Go Shirakawa’s startling Dust Dancing on the Rafters, a compilation from the bloody, turbulent period that followed the peaceful court period in Kyoto. The retired emperor’s passion was for imayo (‘songs of the moment’), the earthy songs of commoners, especially the asobi, the female singers of the road, often illiterate, marginal women. Their voices (along with their night-time favours) often crop up in traveller’s tales, including Bashō’s. How’s this for a come-on to an over-pious traveller: ‘I’d like to go to Yawata / but the Kamo River / flows so fast / and oh so fast / flows the Katsura River! / So set your boat out / at Yodo Crossing / and come to meet me / oh Bodhisattva.’

Such an open-air poem, full of raunchy peasant gusto, is another reminder that this anthology does not over-invest in the monologues of individual poets, most typically the Buddhist monk–poet. Apart from poems by such greats as Nōin, Saigyō, and Sōgi, who became the exemplary models for all pilgrims to utamakura, the book includes extracts from the clan-battle legends of The Tales of the Heike, from Noh plays, and from later travel journals. McKinney’s anthology swells with sociability. After all, what we have come to know as the short haiku poem (properly named here as haikai) emerged from the gatherings of Renga (linked verse) poets who pitted wits to cap each other’s poems at length. Out of such marathons the poetic jewels of Bashō emerged, including his droll and cryptic prose, which facilitated his famous masterpiece, The Narrow Road to the Deep North (or ‘Oku’, which meant ‘innermost’).

It’s too easy to say that this anthology is most worth getting for McKinney’s intrepid revisiting of Bashō (she does all of his Bones on the Wayside and the first part of Narrow Road). It must suffice to note that the complex web of her anthology is meant to lead to it, to equip us for him like no other introduction. An exemplary achievement – especially since she thinks that Bashō is essentially untranslatable because his writing took medieval constructions to the cusp of modernity, and because she thinks the meanings of those poems are not in the words: they are in the hum behind them.

Well and good, I wish to say. Travels with a Writing Brush is a beehive of a book, buzzing with superb commentary and annotations, and bound to last for generations.

Comments powered by CComment