- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Custom Article Title: Anne Godfrey Smith reviews Four Plays

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A variety of plays

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

2D and Other Plays is prefaced by an Introduction by Nicholas Tarling, a colleague of the late Eunice Hanger, paying tribute to her as a writer and as a person deeply concerned with developing and encouraging locally written drama. Her association with the Twelfth Night Theatre in Brisbane in its early days is well known. The verdict of time may well be that her greatest contribution to Australian theatre was the collection she made over the years of unpublished Australian playscripts, and manuscripts of those now published. This collection – the Hanger Collection – is now in the Fryer Library, University of Queensland. A list of the scripts in the collection is given in Appendix B of this volume.

- Book 1 Title: 2D and Other Plays

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $5.95 hb

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

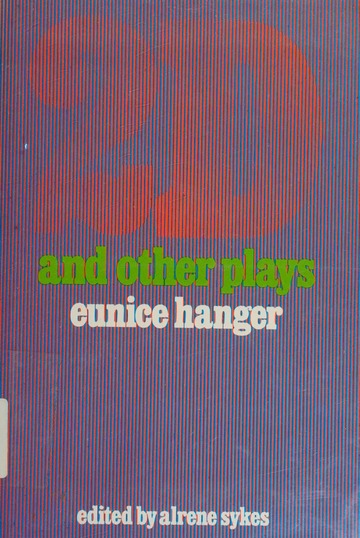

- Book 2 Title: Can’t You Hear Me Talking To You?

- Book 2 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $13.95 hb, $8.95 pb

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Cass, Butcher, Bunting

- Book 3 Biblio: Edward Arnold Australia, $3.50 pb

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

‘2D’ is a three-act drama about a day in the accident ward (male) of a large Brisbane public hospital, and uses the bridging device of a Narrator: in this case, the various sisters on duty in the ward, who address the audience directly at the opening of each act and explain the situation of the men in the ward. Eunice Hanger is a thoughtful and articulate writer, and in these soliloquies are found some of the best moments of the play. She also has the actors playing the patients doubling as the doctors: this doubling being underlined by the Sister, who explains to the audience that as ‘we make God in our image’, so the patients see the doctors as gods and project themselves into those images. Similarly, the women visitors are doubled by the actresses playing the nurses and sisters.

The play as a whole belongs to a pretelevision era, in that it is over-explanatory. The situations and characters derive from other plays about hospitals rather than real life. There is also one scene in which the visiting honorary physician Sir John Monckton-Smith tours the ward talking a medical gobbledygook, quite out of key with the rest of the play, where realism in speech and actions is demanded from the actors.

‘Frogs’ is a one-act play about a city wife, married to a farmer in southern Queensland, who graduates to being ‘bush’. At first unable to kill a mouse in a trap, she discovers she can kill dozens of frogs when she finds them, as long-awaited rain starts falling, blocking the inlet to a nearly empty water tank. The play makes its point economically and with a tough humor.

The most interesting play is the third, ‘Flood’, written in verse. The plot is rather soap opera, involving a heroic, crippled young man, a daring young doctor who wins his spurs in the emergency, a sensitive and misunderstood emigrant from central Europe. The central character, Janie, sister to the crippled young man, is more interesting in her zest for life and her urge to question and explore, but her creator leaves her (to judge from the final scene) with the choice of marrying either the doctor or the New Australian.

The actual moment to moment situation of a town being flooded, the measures taken to cope, the waiting, the suspense, the cresting of the flood: all these come over vividly, whether through dialogue, or through chorus-like sequences, spoken for the most part by several women of the town. It is here, rather than in characterisation and development of relationships, that the strength of the play lies.

Can’t you hear me talking to you is a collection of eight short plays, all locally written and produced – that is, if you regard New Zealand as local, as well as Australia. There are several ‘two handers’ included, two of which are well worth production: - ‘Four Colour Job’ by Gail Graham is a quiet and thoughtful piece about a printer, a New Australian who is a craftsman in the real sense of the word, and a girl who wanders in to ask him to print some cards. In the course of their encounter she learns something of the integrity of the craftsman, and responds to it as something in herself, though at that stage of her development she is not really aware of this fact. Michael Cove’s ‘Duckling’ is a sympathetic and humorous study of Tess, a very young would-be artist who has thrown off the family ties and is living in her own bedsit, struggling with her painting, a tendency to being overweight, and her friendship with Paul from upstairs, who has a steady job and is strongly attracted to her. Leila Blake’s ‘Prey’ is a study of two predators (both male) who confront each other over a tank of tropical fish. The other two hander, ‘Sadie and Neco’ by Max Richards should have been called ‘Masie and Sado’. It is yet another predictably dreary study in sado-masochism, on the same lines as Arabel’s ‘Fando and Liz’ of the early sixties.

‘The Boat’ by Jill Shearer is a not very convincing study of obsessive delusion; ‘Can’t You Hear Me Talking To You’ by Nora Dugon is a play of an elderly couple with no love or liking for each other, but deriving emotional sustenance from a possible crime committed by the old man many years ago. This play has been produced as a radio play, and is perhaps better suited to that medium than to the theatre. ‘Balance of Payments’ by Robert Lord, about a pistol-packing momma, is supposedly black comedy, but lacking point of any kind, turns out neither black nor comic.

Jennifer Compton’s barbed and witty ‘They’re Playing Our Song’ is perhaps the best piece in the collection. In this play she presents four variations on the theme of male/female relationships: an excellent piece for two actors and two actresses with the requisite skills and versatility.

‘Catherine’ by Jill Shearer is a recent publication in the Monash New Plays series. Plays about Australian history rarely get past the documentary educational broadcast stage. This play is an exception: it is a sensitive piece of writing and is dramatically effective as well. The subject of the play, Catherine, was a convict girl on board a convict ship in the Second Fleet of 1799, who, during the voyage was ‘allotted to’ the ship’s surgeon, D’Arcy Wentworth, a gentleman highwayman, whose aristocratic connections saved him from the gallows, but sent him to Botany Bay. Catherine became pregnant, and D’Arcy kept her with him till the time of her death ten years later, though he did not marry her. Their son, William Charles Wentworth, became a notable figure in the early annals of the history of New South Wales.

The action takes place on the convict ship, and the playwright has set it as a play in rehearsal, so that the actors can step back and comment on the characters they are playing. This device enables historic information to be got across to the audience without any suggestion of giving them a lecture, but it creates the problem of the balance between the actors’ scenes as actors discussing the play, and the scenes on the convict ship that they rehearse. The scenes of commentary, and the actors, seem less effectively realised than the ship and the characters on board. The actual recreation, chiefly by sound effects and suggestion, of the convict ship – the suggestion of the packed hell that it was, especially for the female convicts who were the accepted prey of soldiers and seamen alike, is well handled and involving. The characters of Wentworth, Catherine and the old convict, Thomas, Wentworth’s personal servant, are convincingly developed. The play ends with the arrival of the ship at Botany Bay – the actors and director inform the audience of what happened after that arrival. The relationship between Catherine and D’Arcy is echoed by the relationship of the actress playing Catherine with her director, who is also her husband, and their arguments about the kind of woman Catherine was. By the end of the play, both D’Arcy and Hal, the director, have had their stereotyped view of Catherine altered, though neither is ready to admit this.

This play does not seem to have been staged as yet, though it should be: it says a good deal about the darkest chapter in our convict history – the fate of female convicts in the colony – and one that has been little touched on so far by playwrights. It says it with restraint and in theatrically effective terms. It would be particularly suitable for staging in an arena theatre: it needs intimacy, with the audience in close contact.

‘Cass, Butcher, Bunting’ by Bill Reed, is also one of the Monash New Plays. This play is one of those set in a crisis situation with types, not individuals, involved. In this case, there are three men discovered in a small pocket of space left in a mine shaft, after a cave-in. One is an unthinking ocker, one a promising intellectual (naturally gone to seed on pot and now back in the mine), and the third, a madman, obsessed about the torture of cats. At interminable length, the audience is taken through the last two hours of their existence, during which the madman chants his list of tortures inflicted on cats, until he is bashed to death by one of the other two; these two break down into hostile, screaming animals until finally they are crushed by another rock fall. If reduced to about thirty minutes playing, it would be effective grand guignol if you care for that genre.

Since the cave-in is not suggested as having been due to someone’s criminal carelessness, it has to be regarded as an accident, and one for which all miners know they are at risk when they take on the job. The madman’s page-long speeches on cat torturing are not relevant to the situation, but appear simply as gratuitous horror for its own sake. Victims at the point of death make very uninteresting theatre, unless they have previously been established as characters the audience could become involved in, and unless they create their own drama of death when it occurs. Psychological disintegration in the face of death, like soiling one’s pants, does occur as we all know. But without anything more to it, the phenomenon in either case is not material for good theatre. Despite very long, dramatic stage directions, despite the screams, shrieks, expletives, torture lists, sound effects, it is a very dull two hours.

Comments powered by CComment