- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

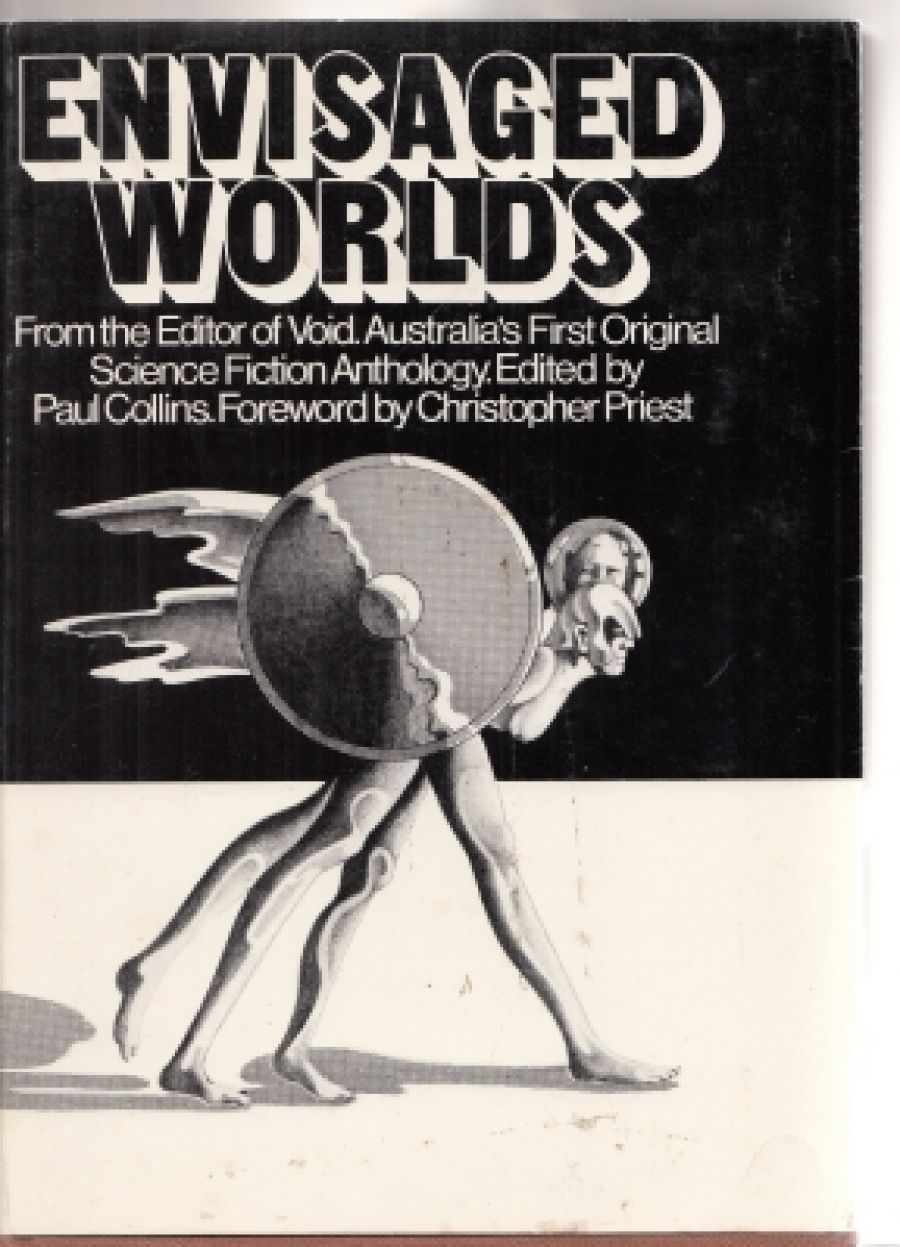

- Article Title: Moira McAuliffe reviews 'Envisaged Worlds'

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Envisaged Worlds is an important anthology, not for the claims it makes, but for the claims it doesn’t.

- Book 1 Title: Envisaged Worlds

- Book 1 Biblio: Globe Press, $9.95pb

In some ways Envisaged Worlds justifies the Australianising intent of the 1977 workshop; many of the stories in the anthology are reworkings of genre – traditional situations and conventions. This is not to demean the anthology. On the contrary. Where else, with or without such training as workshops give, are writers to be published? It is true that there are small magazines (and Void is one), and fanzines, but where are readers (as distinct from fans) able to find such work, unless it appears in a durable format’ such as this? And unless (Australian) science fiction is available to a wide audience as a branch of fiction it will never emerge from its ghetto fastnesses and be recognised for its real importance, that of being the main form of symbolic literature currently available. (It is because SF is the only labelled form of symbolic literature that Lord Of The Rings is sometimes classed as science fiction. And science fiction and children’s literature are conjoined on the shelves of our bookshops in the same simple splendid denigration). In a historical context then, Envisaged Worlds is important in Australian science fiction almost irrespective of what it actually contains.

Almost, but not quite. Being published when it was, Envisaged Worlds is something of an indication of the general state of the art in Australian SF. The tone of the stories is for the most part serious, if not heavy. The settings range from Australia in the near future to frontier – worlds of the far future; the styles vary from flat, staccato statement to dense argument, energetic, unsubtle satire, slightly stylised ex tended yarn and the eeriness of taking the extraordinary for granted. The most striking characteristics of the collection as a whole, is its competence, its feeling of heavy literalness and its sometimes implicit, sometimes blatant misogyny.

To my mind, to qualify as fiction, which is what it is, an SF novel or short story should turn not on a quirk of physics/mathematics, overlooked or unrevealed until the last paragraph, where it hangs the story on aliens, but on the illumination of what is laughingly referred to as human nature as it’s portrayed in the human protagonists or in the psychologically real ‘others’.

Pxzquilchian natives invented for a story are human: they have to be: that is the limitation of the human imagination. It is the differences within the similarities that make the story memorable, worth rereading: it is the interrelation between time, environment, heart and mind that science fiction, any fiction, is ultimately about. The freedom of SF is to invent or remake times and environments, presenting us with otherwise unmakeable images of what it is to be alive, other visions of how we might live.

Van Ikin’s ‘And Eve Was Drawn From The Rib Of Adam’ is a case in point. The narrator is transferred to an all-male construction camp on a world in the Andromeda sector. The peculiarity of this world is that energy forms called Vrills materialise out of thin air, so to speak, one attaching itself to each man soon after his arrival. The narrator’s workmates convince him that the Vrill will be a menace to his health and sanity and suggest to him how he might best control the solid form the Vrill will finally take. Believing them, the narrator finds himself unable to do this, and again believing them, takes the Vrill to Honeycomb Hill to try and dispose of it, kill it. He discovers instead that the Vrill is a frightened parasite, that his workmates have controlled its form, that they have trapped it into a life of rape.

All the elements of this story are resolved in the last line; the narrator’s guilt, self-blame and sadness are beautifully balanced with his awareness of the viciousness and depravity of what was done; the final shock of realisation for the reader is in the similarity of the exploitation of this life – form to the exploitations of our past and present.

The same theme is made explicit in Bertram Chandler’s ‘Not Without Precedent’, a story about aliens invading the world and the last days of Sydney. The point is made here through the style of the invasion and the sexual exploitation of some of the women, and by the presence of an Aborigine who comments on the narrator’s account of the invasion (written for posterity if there be any such) by comparing it with the rock paintings of his own people. Written in the tradition of H. G. Wells and John Wyndham, the story is also a whimsical comment on that style, and has a lovely touch of humor about the Governor General.

Two other stories in the anthology also pick up this theme – one, ‘Better Be Good’, is a racy, tongue in cheek, but ultimately gentle account of a space-pilot-con-man conned by his victims, who resemble large, striped polar-bears; the other, ‘Lillidli The Angel-Maker’, treats sexual and colonial exploitation at every tum of the plot. This story is basically sound, but would have been more complete, more whole, if it hadn’t fallen into the pulp-habit of making over-explicit parallels between our fictional past and the fictional future.

The theme of exploitation recurs in a larger number of stories than any other single theme. ‘The Cage Of Flesh’ is a curious piece, dense but abstract, written in a breathless, sensational, present-tense which, in its self-imposed limitations of perception renders the characters utterly unreal – more utterly unreal, that is, than the writer overtly intends. In an age of media-sex-alcohol and narcotics-drugged boredom, where the wealthy pay an Agency to supply Interesting People for parties (the interesting are poor; the rich are too rich to be interesting), Margarita Graham invites the famous killer Michael Novak to her castle. She is attracted to him by his hatred of and contempt for her; he is attracted to her because she reminds him of his wife, whom he murdered and has a compulsion to keep on murdering. Novak outwits the electrodes planted in his chest to prevent him harming people and does the deed in gory detail.

The contempt in the story for both the characters and the setting is riot confined to the consciousness of either Novak or Margarita Graham. ‘The Cage Of Flesh’ might have began as social satire or bitter, black social comedy, but, like the leading lady, lost its virtue before page one.

The idea of exploitation and violence between the sexes is carried to a bloody conclusion in ‘The Libber’, which begins with the possibility of humor but blackens almost instantly as the hero, Gibbon, a spokesman for Interplanetary Men’s Year, is knocked unconscious by a towering woman as the spaceship they are on slowly blows up. When marooned on a backward, barbaric planet, he is met by a woman, a hunter, who by the religion and custom of her clan kills and eats the men (particularly) of an opposing clan. The story ends with Gibbon killing and eating her. Unlike ‘And Eve Was Drawn’, however, there is no pity in the hero’s mind because of the turn of events; ‘The Libber’ is unsettling because it presents only one arbitrary reduction to horror as the whole reality.

There is a lesser strain of the same tension in ‘The Sentient Ship’, primarily a satire about politics and big business and the connections between them. The story is animated by fairly crude satirical techniques, but forces the reader to laugh by some neatly turned absurdities and its overwhelming vehemence. But there is a strain. The sentient ship is run by a computer programmed with the male intelligences of the three most intelligent (i.e. wealthy) men in Australia; the Women’s Liberation Army demands equal space and so three Women’s Lib intelligences are also included. At first they take no difference to the ship because, the writer alleges, their real desire was to be men; when the ship gets lonely and proceeds to create female companion – ships, its sexual identity is called into question and Sir Sentient Ship (as he is then) goes schizophrenic. In summary the idea sounds like satire extended to pleasant absurdity; in the story there are undertones of vehemence and personal bitterness about this that seem to be lacking in the descriptions of the seamen or the political machinations. But perhaps I look with a jaundiced eye.

‘The Girl Who Walked Like A Cat’ looks at the same problem from the other viewpoint, and with a deal of’ humor that softens the impact of what is being said. Fiona Mellaby is a model; she has a cat, Hugo, to which she is very attached. Her fiancé, Richard (who is a wet and a weed, though this is never explicitly stated) is alternately welcomed and rejected by Fiona, who is gradually, during the course of the story, turning into a cat and producing a kitten by Hugo. Marriage to Richard is implicitly a fate worse than marriage to Hugo, but the motive is not so much Richard’s shortcomings as Hugo’s – longcomings? – and the excitement of being physically a cat – which only then becomes, on reflection, a humorous escape from Richard’s naive and mistaken expectations and the assertion of Fiona’s real personality. It is a gentle story, and an image that remains in the mind more durably than some.

‘Project Hemingway’ is a very pleasant, competent story bubbling with verbal wit and generosity towards its characters; the sexual humor of it is of a piece with the rest, male, warm and verging on the compassionate, in stark contrast to the eerie, believable image of despair presented in ‘A Marriage Of True Minds’ where the hero, Phil, in love for the first time, desperate because the affair is going to end, imprisons his lover’s personality in a bronze cube which he has invented for brain research. He begs the narrator to imprison him with her, which he does. The tone of the story is quiet, mundane, an extended, stylised conversation, horrifying in the narrator’s calm acceptance of such a literal translation of the idea. (Equally horrifying is the thought that the hero knew the affair was going to end and engineered this unbreakable ghastliness at that point without asking the lady, and that the narrator did not question this. Ah, mateship. If only more of us had it).

A Marriage’ is the first of three stories by people who attended the Le Guin workshop. Like ‘A Marriage’, ‘A Compassionate People’ and ‘A Matter Of Pushing The Right Buttons’ are competent and genre realistic; their respective tones; however, are depressingly similar, but the odd vivid glimpse of the landscape leaps out, and at this level the stories are gratifying and demonstrate potential. For all its commas and indigestion, ‘Freeroamer’ has more flashes of naturalistic detail than one would expect and is a much more satisfying offering than ‘Nemaluk And The Starstone’, which bids fair to be the SF equivalent of a used tea-towel with angst and Aboriginal motifs.

The remaining stories – ‘Beyond Aldebaran’, ‘Strike A Light’, ‘Creator’, ‘What Evil Must Do’, ‘The Witch Of Norrnansk’, ‘The Basic Difference’ and ‘The Butterfly Must Die’ – are basically reworkings of themes and ideas too familiar to recount. Suffice to say that they are competent and evidence that SF in Australia is a going concern.

Envisaged Worlds is also an important and fascinating anthology on its own terms because some of the worlds envisioned are real, and visions of the world and humanity are all that we, as human beings, can produce; in every case it is the quality of the vision that we savor and keep or discard, and that is our business as human beings.

Comments powered by CComment