- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: War

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: R.A. Swan reviews 'Citizen to Soldier'

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is a most interesting, readable and, in a larger context, valuable book. It deals with written recollections collected from some 215 living veterans from the First A.I.F. (some have since died) – a list of their names is included as an Appendix – detailing how they felt about the War as it approached and when it commenced, and also what led them to enlist at the time. Each informant is allowed to speak for himself, with his own peculiar spelling, punctuation end style of writing; in effect, the outcome provides a broad picture of the social origins and nature of this cross-section of soldiers.

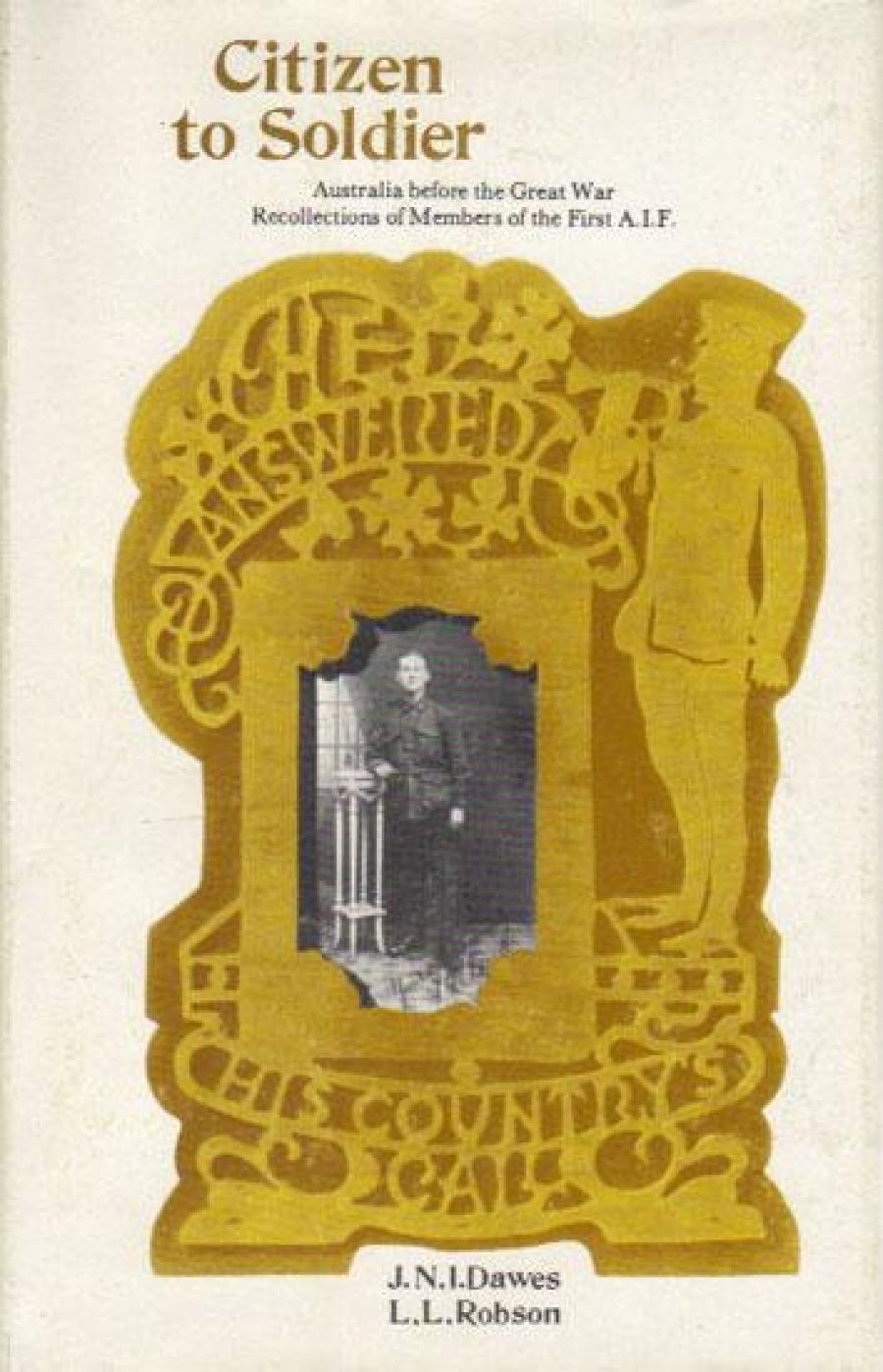

- Book 1 Title: Citizen to Soldier

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, x + 211pp, $12.60 hb

The basic idea is of ‘... an ‘adventurer’ or ‘tourist’ group followed by waves and waves of more serious thinkers, and interspersed with boys reaching enlistment age ...’ In other words, the first wave of recruits was full of eager enthusiasm for a fight on personal, patriotic and adventurous grounds, the patriotic sentiment relating to an indigenous Australian nationalism which was seen to be compatible with membership of the Empire – this first wave saw Australia as being ready for a war as a test of nationhood. But as the war dragged on and the casualty lists grew longer, succeeding recruits expressed different reasons – following the example of friends and relations, the belief that enlistment was the correct thing to do, sensitivity to social pressures, a sense of duty, and so on. However, mention is made at the end; in a Retrospect, of the appearance of disillusionment, cynicism, and growing criticism of the way the War was being conducted – attitudes that doubtless helped to defeat the government in the two Conscription referendums of 1916 and 1917 respectively.

Apart from the descriptive and social value of the contents of the book, what is its significance as a contribution to the true history of the period covered? First, it must be emphasised that the testimonies of the informants, made some fifty years after the events in question, would need to be complemented by material from contemporary sources, written material preferably, private, public and official, before their proper value could be fixed. A testimony of this nature is very close to an oral testimony proper, albeit by literate persons in this case, and relates to a known historical tradition. Such testimonies – 215 in all – are that tradition as interpreted through the personalities of those persons, and are colored by their personalities. Furthermore, traditions are altered, more or less consciously, to fit in with the cultural values of a period. In this instance it would need to be known how the historical tradition in question was affected by the cultural values operating in Edwardian Australia, and again how the changing cultural values in Australia over the fifty years lapse of time before the informants made their testimonies affected their memories and recollections, and so decided what they thought was really significant and suitable for inclusion in their respective testimonies.

In passing, it is interesting, and regrettable, that only one testimony of a contemporary documentary nature appears in the book – a letter written by the informant to a friend on 23 July, 1915 on the subject of enlistment (pp 121-124).

It is hoped that further research will be carried out to unearth primary source material in the period and tradition, when the contents of this book will take on an added significance and value. In the meantime, the book should be read in conjunction with Dr Robson’s two valuable books The First A.I.F.: A Study of its Recruitment, 1914-18, and Australia and the Great War, 1914-18, together with Bill Gammage’s most impressive documentary work The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War.

Citizen to Soldier has been very well produced by the Melbourne University Press. A hardback, it is strongly bound, the paper is semi-glossy and good, and the type is clear and most readable. It is a pity that a few illustrations could not have been included to give some color and visual interest to what is otherwise an interesting and useful contribution to the history of the period and its tradition.

Comments powered by CComment