- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Feminism

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Colonial Eve

- Article Subtitle: Sources on Women in Australia 1788-1914

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

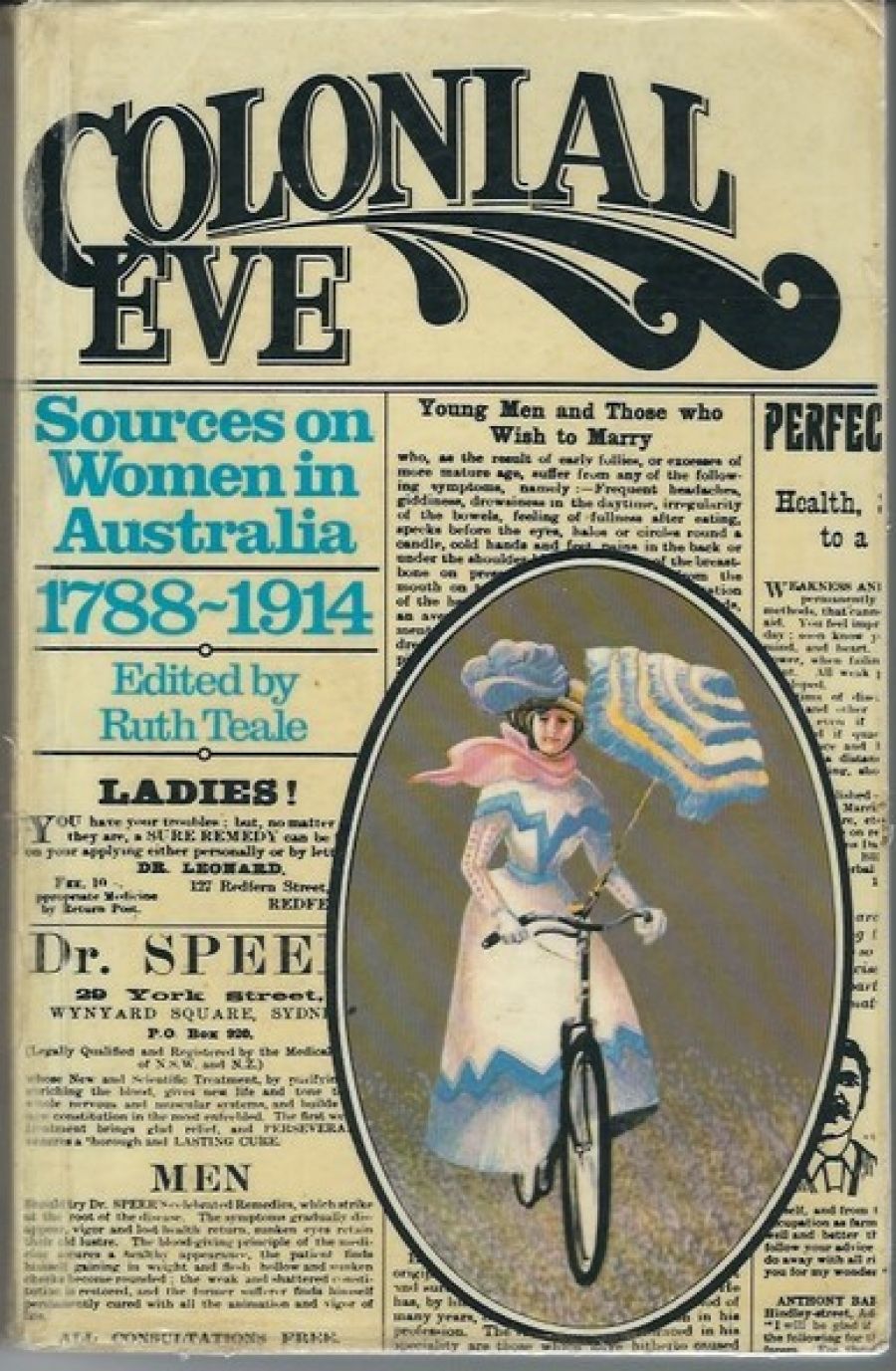

It would be remarkable indeed, if this collection of documents did not fulfil its broadly stated aim of interesting the general reader of Australian history and adding something more to the available literature for women’s studies courses. For the general reader it is a pleasantly presented book, utilising line drawings, cartoons, and advertisements as they appeared in the journals and newspapers of the late nineteenth century. The documents appear also as very extensive illustrations to the editor’s commentary, and although a querulous reader might complain that it is not always clear where the commentary ends and the documents begin, it is an easy book for browsing. As well, because documents of this kind have not been over-used in the conventional collections on Australian history, the general reader is bound to find something that is either new or stimulating.

- Book 1 Title: Colonial Eve

- Book 1 Subtitle: Sources on Women in Australia 1788-1914

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, 299pp., bibliography and index, $6. 95pb. ISBN O 19 550545 x hb. ISBN O 19 550546 8 pb.

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

It is also possible that those who feel timid or diffident about the whole question of women in history may find this an easier book than most to begin with. It is simple in its approach and quite unthreatening in its arrangement. There are two main sections – ‘The Convict Era 1788-1850’ and ‘The Victorian Era 1850-1914’. In the first section convict women are juxtaposed with free women and the main subjects covered are the various forms of convict and immigrant administration and questions of relative worth and morality. In the second section, ‘The Victorian Era’ as it is rather misleadingly headed, the contrast between women at home and with their families, and women in public and their gradual movement towards emancipation and participation in the work force is used as an organising concept. Some attention has been given to each of the, by now, standard questions about women in Australian history, the behaviour and quality of the convict women, the history of female immigration, the servant problem, the sweated trades, the birth rate, suffrage, emancipation, entry into the professions. The array of evidence is wider and the interpretation bolder than might have been thought proper before the 1970s resurgence of feminism, but disappointing in the light of feminist challenges to Australian history as a whole.

The emphasis in this collection is still the official document. The ‘recognised corpus: of primary sources’ which Ms Teale wishes to identify and establish is derived essentially from government reports and inquiries, bulked out in time-honoured fashion by some newspaper, journal, and literary texts. The use of cartoons and advertisements is a further refinement of technique, but it also emphasises a crucial weakness, viz., that most official and public preoccupation with women is concerned with their failures and supposed inadequacies. Cartoonists are not in the business of sympathy; nor are they women. It would hardly be acceptable to try to produce a volume of documents on men in Australian history using only inquiries into criminal and other irregular forms of behaviour, with the occasional report of a lodge meeting, illustrated by cartoons and advertisements for sex aids and hair restorer.

Such a perspective may seem far-fetched, but it highlights the fundamental problem of the task to which women’s studies courses have addressed themselves – and for which, incidentally, they will find this book helpful mainly as an example of what not to do.

The problem is this. Far from being a fad or a frivolity or an optional extra, women’s history demands and offers a completely revised approach to our study of the past. It is not merely a mailer of going through the old outline and pulling the women in where they have obviously been left out. It is not a mailer either of going through the old collections of sources and carefully indexing all the references to women. Even the standard concepts of dates and periods will not do – a dilemma already encountered without a proper solution in this book. For as every student knows, transportation to New South Wales ended in 1840, and in 1852 to Van Dieman’s Land; the Victorian era began in 1837 and ended in 1901. But such dates are not very significant for most women’s activities. Either one is dealing in generations or in the imperceptible transmission of ideas over much longer periods of time. It is therefore probably quite accurate as a description of the content of ideas, manners, and morals to label women ‘Victorian’ between 1850 and 1914, but it is also anathema to the precise historical mind. It is in this search for concepts and frameworks which will encompass both the differential time-spans and the differential rates of change in women’s worlds, as well as the known, established periods, dates, and eras of the public world, that women’s history runs into accusations of sloppiness and inaccuracy.

Likewise, there are problems about the use and interpretation of evidence which call into question a great deal of the standard doctrine about bias or balance. Ms Teale hopes that she has presented us with a ‘balanced view of women’, but what does balance mean here? It is clear that she has not hesitated to use, without comment or question, men’s accounts and men’s comments on women’s behaviour and activity.

Very often, there are only men’s accounts. In some cases she has given a piece from a man and a piece from a woman, but is this what is meant by a ‘balanced view’?

These basic problems, of period, terminology, and methodology, all of which are under intense discussion, and not only among feminist historians, are still far from satisfactory resolution. Questions of interpretation, are, however, more straightforward and more accessible, and it is on these grounds that this book is likely to irritate the very talented young persons who usually constitute the classes in women’s studies. A strong line of interpretation or an inescapably coherent one is both visible and open to attack – as has been seen often enough in the critical reception given to previous feminist interpretations of Australian history. A messy or not fully coherent interpretation may go unchallenged because to attack it seems petty or because it is just not worth the trouble. In this case the problem is sometimes inconsistency sometimes lack of clarity.

Once it may have been possible to prepare a book of documents about women in Australian history which was pleasant, inoffensive, intelligent, but thoroughly ladylike. Feminists may be shrill and far from ladylike, but they also have something to say which commands attention. Women’s history is no longer an optional extra. Women have taken initiatives in historical interpretation. In this, as in so many other areas they are no longer dependent or subservient in their relations with the male establishment. They must now seek to be honest, consistent, thorough, to work out their own patterns of integrity which are as valid and as convincing as any others which have served to advance humankind. And they must strive to present their ideas in such a manner 1hat they cannot be ignored or brushed aside.

In its uncertain, unclear, deferential attitude and assumptions, this book falls short of the aspirations of most women’s studies courses, and it may be that even the general reader will be amused for a brief moment, but find it lacking in real integrity and therefore an easy book to lay aside.

Comments powered by CComment