- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's and Young Adult Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Slaying the Dragons of Injustice

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I know nothing of David Martin’s childhood or family, but I think that he must come from a long line of slayers of dragons, and that somewhere during the formative years of his childhood he listened to many adult conversations on social justice and human dignity. At any rate, his adult life has been spent dealing with dragons, in one way or another.

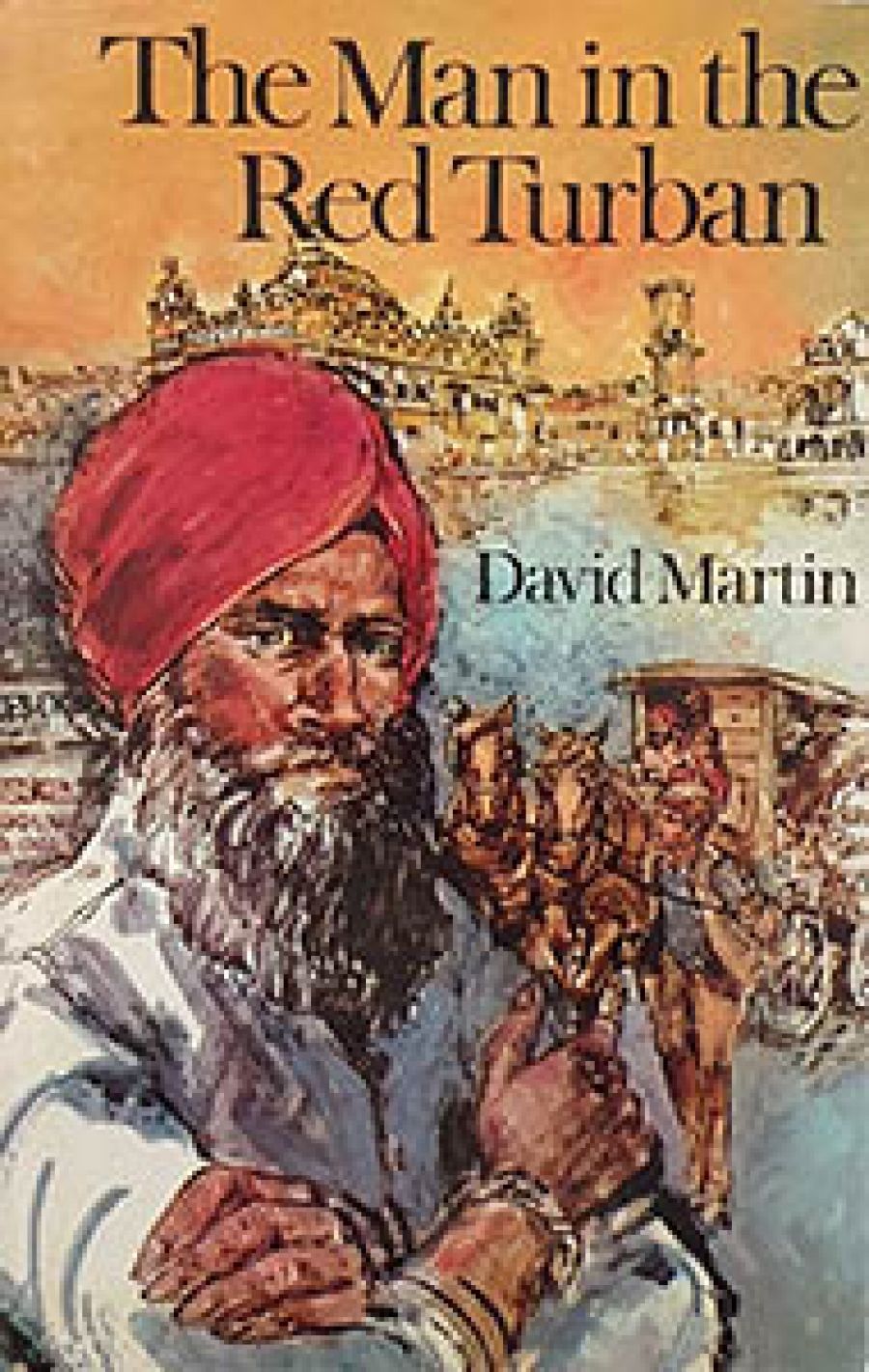

- Book 1 Title: The Man in the Red Turban

- Book 1 Biblio: Hutchinson, $6.95 pb, 168pp

In 1970, David Martin's writing took on a new focus. He began to write for young people, rather than adults. Children's literature is now an important and respected genre in both England and America, but in Australia it is still seen, more often than not, as the literary equivalent of Floral Art; a suitable occupation for middle-class ladies with time on their hands. British and American authors of the calibre of Ursula Le Guin, Joan Aitken, or Robert Nye need make no apology for writing for young people as well as for adults, but in Australia there is still a hard dividing line; with the exception of Colin Thiele, I can think of no other major Australian adult writer who has elected to concentrate upon writing for young people. With Hughie, published in 1971, Martin not only proved himself able to write in this selective field, but became the first Australian young people's author to choose as a theme the problems of minorities and the issues of prejudice. Hughie is still a landmark, one of the very few junior novels about contemporary urban Aboriginal life; it was followed by Frank and Francesca, with a migrant theme, and then two historical novels, The Chinese Boy of the gold fields and The Cabby's Daughter, a sad story of the role of women at the turn of the century.

And so to The Man In The Red Turban. With this novel I believe that Martin has at last found his authentic voice. His is previous books for young people, interesting though they are, seem to me incomplete, not quite realised; they abound in good ideas not quite carried through, in marvellous minor characters deftly drawn and then abandoned, in heroes who seem more symbol than reality. All this is changed, however, in the story of Ganda Singh. It is as though at last David Martin’s heart and head have come together, and the result is a superb story; a good read, a fast and often funny adventure, a thought-provoking novel with relevance for today.

The story is set in the 1930s, at the time of the Great Depression. Ganda Singh is an Indian, one of the travelling hawkers who were a familiar sight in the Victorian countryside of that time, bringing an assortment of household wares to the widely spaced farms and villages in the days before the automobile had revolutionised transport and communication. Ganda, and the reader, are immediately involved in the problems of young Griff Williams, a school leaver with no prospect of a job since a third of the adult workforce is already unemployed, the son of an out-of-work mechanic whose own father had been killed in the Welsh mines. Griff’s great passion is horses, and he is about to appear in court on a charge of having 'borrowed' a neighbor's, and had an accident (even as today's country youngsters get into the same trouble with someone else's cars). Griff’s father returns from itinerant work further along the Murray in time for the hearing, and the magistrate orders that he must whip the boy as punishment. This Will Williams finds he cannot do: 'not like this, not in cold blood ... like a sort of convict. It's against everything I believe in'. Will leaves for the fruit picking, and Griff s mother persuades Ganda to give the boy a ride as far as his aunt's homestead, realising he is humiliated and confused by his father's refusal to carry out the punishment. At Aunt Olly's, word arrives that Will is being hunted by the police, and both Griff and his plucky cousin Bron resolve to find and warn him, with Ganda's wise and amiable assistance.

From here the story itself resolves into a quest, enlivened by such incidents as Griff s efforts to help Ganda collect bad debts, an encounter with a seedy youth who dreams of riches while peddling coat-hangers, a very funny diversion involving the Reverend Joshua McQueen and his ‘work of conversion among the Asiatic heathens’. Flitting in and out just offstage is the other Sikh called Tulip, a mysterious presence who also provides the link to Ganda’s past. This is recalled in a series of flashbacks, during which we see the young Indian boy – the same age Griff is now – in his village in the Punjab, falling in love with the girl Ravindjerit; their marriage, the grinding poverty, the family debts that eventually bring the young Ganda to Australia in the hope of a quick return; and then the long years of separation and longing, alone in a strange land.

When Ganda and the two youngsters eventually track down Griff’s father, he is tucked away in an Aboriginal camp on the banks of the Murray, nursing a broken ankle. Will had been organising the fruit pickers to agitate for free transport in the empty freight cars, and was injured in a fracas with the railway police. Now he was in hiding, hunted by police determined to make an example of this trouble-maker, and teach the itinerant workers a lesson. His eventual capture – after a fast and funny battle – sells the stage for a surprise ending, in which both Griff and his father achieve something each has long desired, and Ganda at last is able to return to his homeland and his waiting wife.

The story flows as smoothly as the Murray River that it follows. David Martin paints a warm and loving picture of the Australian countryside, and of its people, shaped by the land and by the society they live in. There are many heroes, all striving to do their best within the confines of their own limitations. There are quirky rogues, too, but no villains, except socie1y itself. The quest is a search for social justice, a statement of human worth and courage and dignity. For the young reader, it will clothe in flesh and feeling the dry facts of the Depression, and offer a thoughtful parallel to the social climate they themselves will soon inherit. David Martin may have mellowed somewhat with age, but he still has a young man's crusading spirit.

In a preface to The Man in the The Red Turban, he quotes a Sikh guru:

I turn sheep into lions,

Outcasts into warriors;

I make the poor to be like kings.

David Martin does too, and I think young readers will respond.

Comments powered by CComment