- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Chatting about the Painting

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘To paint’, Ian Fairweather once observed, ‘one must be alone.’ True enough, you think, though hardly deserving of quotation. Down the years all kinds of artists have made the same observation, yet not many of them have been as consistently forthright when essaying the value and aesthetic nature of their lonely activity. Fairweather was an exception. ‘I paint for myself,’ he went on to add, ‘nor do I feel any compulsion to communicate, though naturally I am pleased when it seems I have done so.’

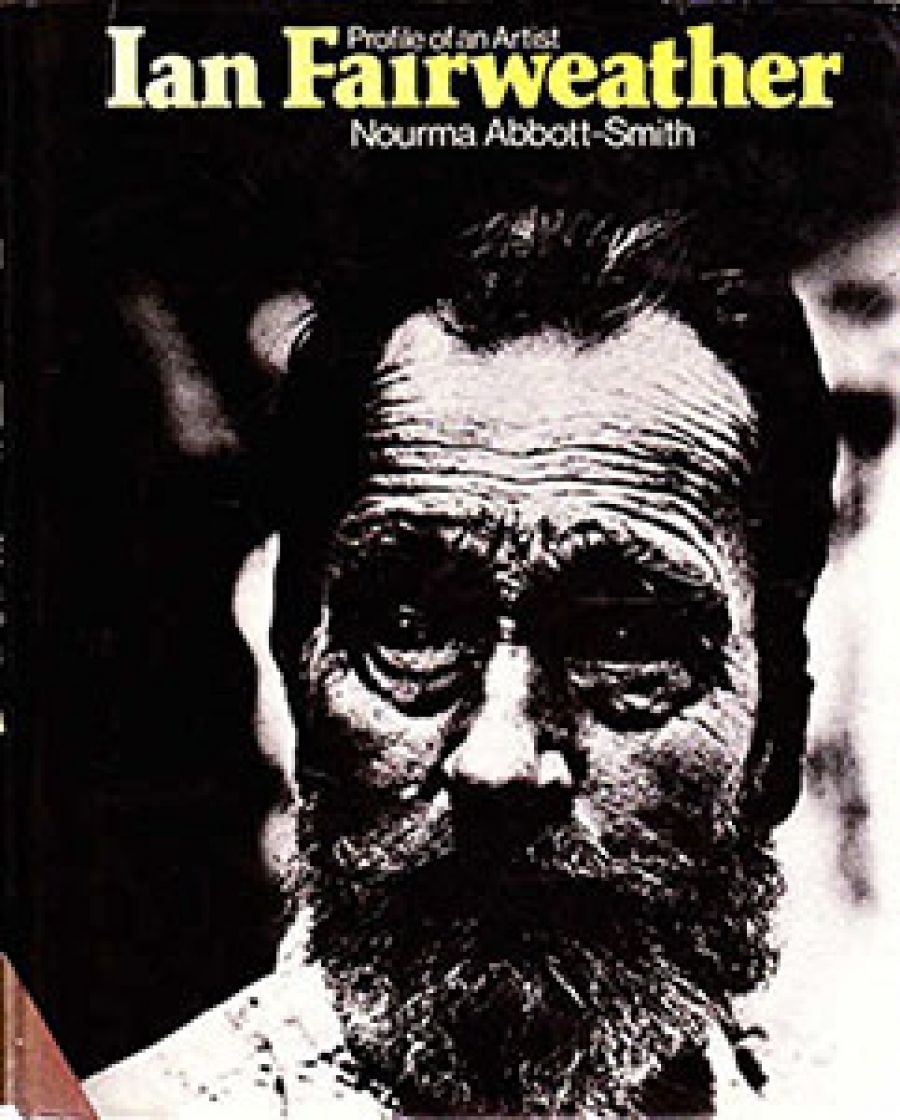

- Book 1 Title: Ian Fairweather

- Book 1 Subtitle: Profile of a painter

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $16.95, 186 pp

- Book 2 Title: Conversations with Australian Artists

- Book 2 Biblio: Quartet Books Australia, $14. 95 hb/$9.95 pb, 231 pp

What kind of man was capable of such disarming diffidence? Hunting through Nourma Abbott-Smith’s ‘profile’ a faint picture emerges: the ninth and last child in a military family, the lonely childhood on the Isle of Jersey, separated from parents and other siblings, then an interlude in Switzerland, climbing dangerous peaks and cramming for Aldershot. Then follows the Western Front, prisoner of war camp, fruitless attempts at escape, and a falling backwards into art, the Slade, Chelsea, visits to Norway, and so on. The brute, bare facts, served chilled and almost left uneaten.

Regrettably, all we end up with is what we knew – the stock-image of the Bribie Island eccentric, impressed deep into the grey matter of the brain by countless newspaper articles. Ah!, earth colours, bush hut, and trivia of that sort.

It may well be that Fairweather’s eccentricity allowed him to create the paintings he did, yet now it’s time that the artist be extracted from that cushioning myth. And to do that, you have to come to grips with that statement of Fairweather’s quoted at the beginning of this review – and, I might add, on the first page of the preface to Ms Abbott-Smith’s book.

And the real point of issue is not the biographical events which shaped this attitude (they can be pin-pointed by anyone with even a modicum of insight, though I am not too sure that Ms Abbott-Smith is aware of them) as the currently unfashionable nature of Fairweather’s opinions. The compulsion to communicate is these days a universal one; anyone who resists or denies it is called a misanthropic misfit and kicked hard for his or her troubles. Quite unintentionally, Nourma Abbott-Smith has delivered a beauty to the rear of Ian Fairweather, deceased. After reading this book, you almost wish he had vanished on that epic raft voyage to Indonesia. From her profile, he emerges as an irritating, objectionable, and exceedingly childish figure.

In the latter chapters the author’s account degenerates into a slavish collage of laudatory reviews from the newspapers. A decent bibliography could have moved such material off-stage and thus allowed the author to pursue the one interesting idea she raises – and that is Fairweather’s fundamental Victorianism. She offers no evidence for this other than the fact that he was born within the Victorian era, yet the suggestion is certainly an intriguing one. Fairweather’s formal masters may well have been Modigliani and other painters of the School of Paris, but in spirit he does seem a kind of twentieth-century Burne-Jones, hopelessly pursuing an unattainable vision of grace – and, thus, necessarily a recluse. But all this is mere speculation. If Ms Abbott-Smith had done her job properly and not lazily strung together so much raw material ... if, if, if.

You don’t have to open Geoffrey de Groen’s book of conversations (‘interviews’ better catches their character) with twenty, mostly young and in some cases very young, artists to know that times have certainly changed. Communication? Sure, we’re into that! ‘I think art should communicate to a wider audience,’ Jenny Watson affirms, before going on to observe that ‘the perception of real images assumes a mass audience’. And, you wonder, why? Just what is the difference between the image of a pressure-cooker and that of a simple triangle? Can’t all people see?

In recent years the interview has become an increasingly popular form of art journalism, yet I cannot help doubting its utility. Geoffrey de Groen, in his prefatory remarks to the book, is under the illusion that as the interview allows artists to have their say then it is a serious alternative to genuine criticism. It seems to me an astonishing assumption to make. Interviews may provide valuable critical material, yet only a brave man would trust the mouths of de Groen’s twenty horses. Or any twenty, for that matter.

Like most people, artists are also modest creatures, and in nearly all of these interviews (Jenny Watson, the youngest here, is a splendidly dismaying exception) you detect a vague admission of honourable failure. Up till now I’ve failed but one day I’ll get there! I would have thought that such a note would undercut the main reason for interviewing them in the first place, but never mind.

In nearly all the interviews de Groen first begins by asking his subject just when he or she first become aware of art, and then the focus moves to a discussion of art in general, to the artist’s particular working procedure, or to their feelings towards Australian society. All too rarely do the discussions take wing. We do, however, have numerous citations on the value of overseas travel and experience (you must go to London or New York, otherwise you’re only brute and unfinished!), a few anguished comments on the allegedly elitist status of art (Ken Whisson, un-interviewed, would have put him right on that score), and a few lamentations about the allegedly stultifying sameness of Australian society (providing us with further illustrations of our masochism). Australians must be the only people in the world who have to leave their country before they allow it any complexity or interest.

There are 28 pages of notes at the end but they are next to useless. Some artists have bibliographic entries, others do not. As well, there are certain niggling errors in the text. The Melbourne painter John Howley is called Howie, and who, I’d like to know, is Giacommetti – two ms, two ts? Not Alberto, surely!

Despite the fact that both books are departures from the picture book syndrome, neither of them can be considered contributions to our knowledge of Australian art.

Their intellectual idleness is offensive.

Comments powered by CComment