- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Reviews

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Food, Wind, Dreams and Books

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

One late afternoon in early summer I went to the launching of Helen Arbib’s Looking at Cooking (Helen Arbib Publications, $3.50, 80 pp) in a beautifully restored and reanimated old house in the Rocks area of Sydney. On the way to Lower Fort Street I’d indulged in one of my favourite meanderings past sentimental landmarks. Among these is a section of Windmill Street, and the Hero of Waterloo Hotel.

- Book 1 Title: Some Early Australian Bookmen

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian National University Press, $21, 65 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The building where we talked about the new book was only three or four doors along from where Ray Mathew once lived so, as I nibbled Helen Arbib’s nice appetisers and drank cold riesling, I thought of Ray and some other nostalgic matters during intermittent hushes.

The intermittent hushes, so welcome in noisy gatherings, stopped conversation every time a train roared across the Bridge opposite. In nearby Kent Street heavy trucks thundering by put an end to a dream we once had of going to live in the Rocks. One of my musings was about the rarity of food in Australian writing. There are pies in Jonah and The Swan, there is damper and tea and mutton in various volumes and plenty of beer; Richard Mahony has sandwiches, trifles, and patty cakes but off the top of my head I can’t recall a single instance of real relish for food: nothing to compare with Dickens even in Patrick White, who is a superb cook. Not once do I remember a description that made me hungry as I read: no recipe so loving in detail I could follow it for myself.

Perhaps the proliferation of enticing Australian cookery books in shops, and of food articles in newspapers, responds to an arcane local craving for what our fiction lacks as to gastronomy. Horrible word, gastronomy. I held the new book and pondered the subtle charm of Helen Arbib’s series of successful ventures. In shops they look appealing. Their narrow shapes catch the eye as do their restrained covers. Their narrow shapes catch the eye as do their restrained covers. They are not garish. Their illustrations do not cause long-established housekeepers to despair because none of their bowls and basins are in primary colours, or to feel inferior because their soufflés never attain such impregnable towers. Inside an Arbib book are feasible imaginative recipes interspersed, in Looking at Cooking, with all sorts of surprising historical snippets and an interesting central essay about the food and dining habits of our forebears.

If trains on the bridge, cranes on the wharves, and trucks on the roads make the Rocks nowadays so noisy what was the decibel level in its raffish heyday? Apart, that is, from the human noise of an area catering for the thirsts and hungers of sailors and others and the racket from inward and outward cargo handling when iron-wheeled drays clattered on cobbles? One rattling, clanking, squeaking source must have been the three windmills on Millers Point. Altogether Sydney had nineteen windmills, whose sails are a feature of many early drawings of Sydney, Darlinghurst, and Paddington.

It really seems extraordinary that since Norman Selfe’s systematic research into Sydney’s windmills was published in 1902-3 in the Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society no one, until Len Fox, has written at all fully about these machines which ground our forefathers’ flour. Fox’s Old Sydney Windmills (Len Fox, $10.50, 80 pp) is a medium length well-illustrated account of these mills with a brief comment on water mills, mills in country areas, and in other states. For the Sydney mills he gives histories, describes what is known of their fates (at least one was used for building stone for still extant cottages) and explains some of the engineering problems and principles involved in their construction and operation. The people who built and worked the mills are not forgotten although information about most of them is scanty. The oddest Sydney mill, and very improbable it was in every way, was on top of Barnett Levey’s Royal Hotel and Theatre. It may, as has been said, have been the first Australian skyscraper but it was a safety hazard to a degree that makes one, for once, feel some sympathy for Governor Darling who opposed it. It was a commercial failure and, at least on its first site, had a short life. As to safety the 1805 Sydney Gazelle (though not quoted here) carried a report of a child shockingly injured by a windmill vane, and a warning to parents who live near these machines. There are also early Gazette accounts of damage caused by vanes blown adrift in storms.

Len Fox explored on foot as well as in libraries, and where diagrammatic explanations are helpful supplies his own. In its pioneer and privately printed form it is cheap to buy and pleasant to handle though some of its illustrations are rather small and smudgy. Royalties are being donated to the National Trust. The windmills book ends with a poem, ‘Sailing Ships, Windmills’ which is also the first in his small collection of poems, Gumleaves and Dreaming (Len Fox, $6.95, 30 pp). Two verses read:

Where now the sails that made music?

Where the towers with their grace?

Where is Jack the Miller?

Who can remember his face?

Nineteen mills on the ridges –

Now not a stone in place.Mary Gilmore remembered

Sailing ships at the Quay,

The ghost of a mill at Craigend

They took a small child to see;

An aging poet remembered –

Now where is she?

I want, though, to make a further point about the Windmill book. Len Fox tells me that though it has not been on sale for long already several people have contacted him with additional and valuable information. Too many people, including some ‘experts’, forget that until material is in the public arena no one can respond to it, and books reach readers in ways that articles in learned journals seldom do. This is an important aspect of publishing overlooked not only by lay people but by one or two lofty academic publishers who seem to think all scholarship should rest in their domain, although the recent standard of editing of some University Press books is little to their credit.

I would hope that when Fox assembles the new material he is acquiring, some commercial publisher will issue an expanded edition of the book designed to match the excellence of its contents. A new edition might also delve more into some statistics of the industry – quantities milled, trading customs and so on.

Meanwhile we can be thankful that nowadays Australian publishing displays a variety of forms and philosophies and is conducted by many people from the long-established to the ‘alternative’. Fortunately healthy adventure tends to break out in both camps, though I think we might regret, with some qualms for the future, that this industry, so important for our own identity, is so frequently divided within its own ranks and so little able to arrive at even the temporary semblance of a common cause on occasions when unity might lend strength. It is good to have individual philosophies, and to preserve proper commercial independence and, indeed, proper commercial secrets; but it is not good when tribes are at the mercy of their common enemy, the Philistine, because of internal divisiveness. It is also not a good thing when certain publishers continue to exploit their lifeblood, that is authors, in thoroughly. cynical ways.

It must often have been much simpler for the founding fathers of Australian publishing when the production of local books was associated with bookselling, and when talented authors were valued greatly for their writings, even though one or two of them were notoriously difficult to deal with. By coincidence, two of the towering figures of early publishing in this country were Scottish migrants, both called George Robertson. They were not related. George the elder, although he had great success in Sydney, eventually in partnership with Mullen became chiefly associated with Melbourne; the younger Robertson, in partnership with his friend Angus founded the famous Sydney firm.

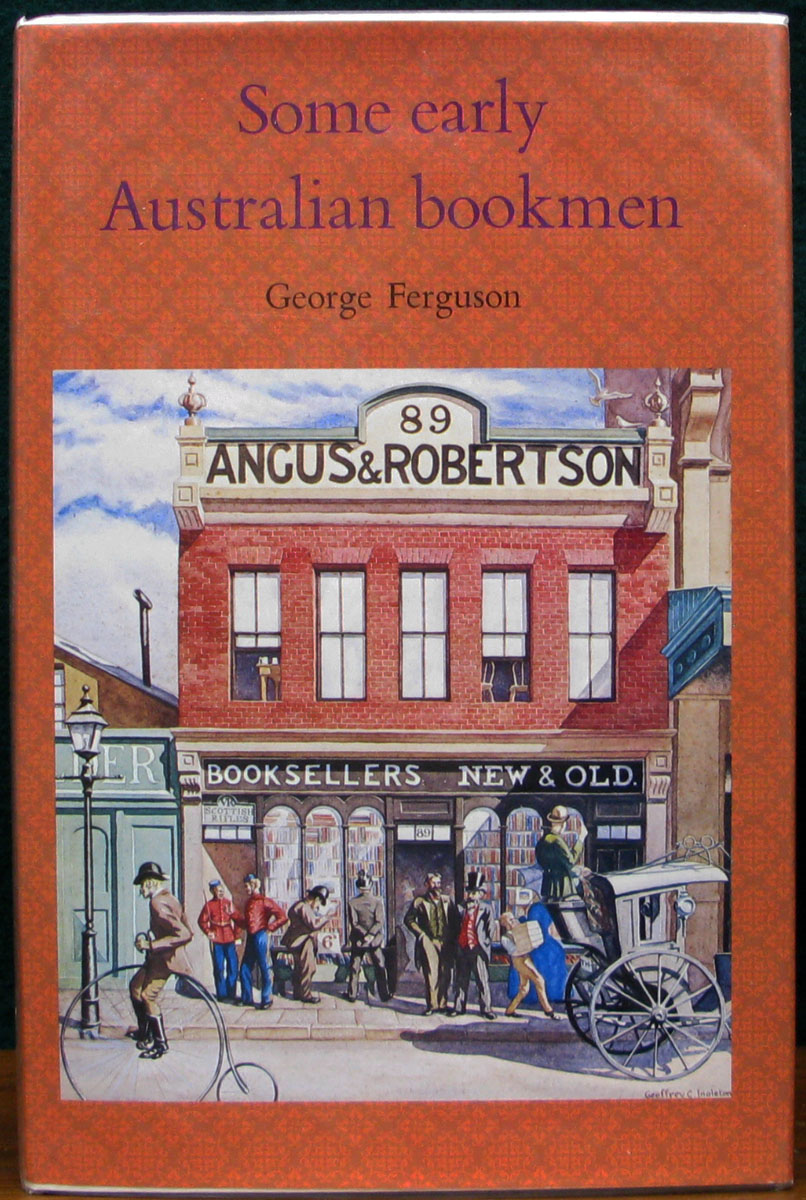

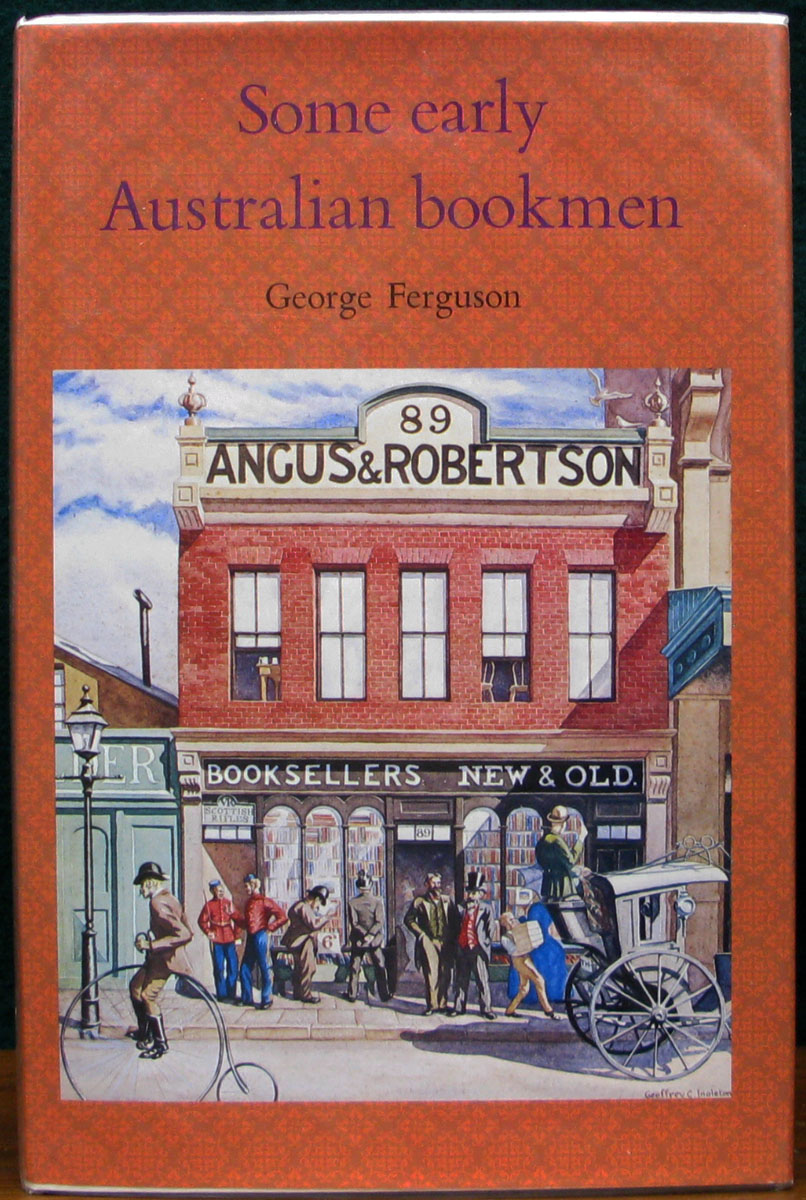

Some Early Australian Bookmen (ANU Press, $21.00, 65 pp) has been written by George Ferguson, himself a notable bookman, grandson of Robertson of Sydney, and son of Sir John Ferguson who compiled the Bibliography of Australia. The new book in a limited edition of 1000 is beautiful, and most fittingly commemorates the addition to the Australian National University Library of its millionth book. As the title suggests the account is not exhaustive, but after discussing some very early booksellers and occasional publications, concentrates on a few only of the several important figures of the second half of the nineteenth century, and the businesses they founded, particularly Robertson & Mullen and Angus & Robertson.

Not long ago, exasperated by some derogatory talk about small publishers, I said: ‘Even Angus & Robertson were small once.’ I hadn’t realised how small. David Angus began the venture with fifty-pound sterling of saved capital, and his first advertising leaflets were handwritten by a friend to save printing costs.

Soon after the firm was established Robertson began to buy and sell ‘books, pamphlets, manuscript maps, and prints relating to Australia, New Zealand, and the South Seas’. He influenced David Scott Mitchell who turned his hitherto general interest to this field. Fred Wymark, whom Angus had taken on as a boy, became a keen expert about Australiana. ‘Perhaps the most lasting and important of all Robertson’s activities as a bookseller lay in his imaginative understanding of the importance of the early literature of his adopted country at a time when few people paid any attention to it,’ Ferguson says. Robertson spoke strongly in support of the establishment of the Mitchell Library, and acted deliberately in choosing outstanding books by Paterson, Lawson, and other writers of the nineties to establish a publishing program.

An important Angus & Robertson archive is, appropriately, now held by the Mitchell Library; a description does not come within the scope of Ferguson’s book but it, too, probably began with Robertson, who, from the firm’s beginnings in publishing, kept authors’ correspondence. Later, but still early in its history, the firm collected complete files of reviews, manuscripts, and a great deal of artwork.

George Ferguson himself was later responsible for building and maintaining these archives and, after World War II, with Grace Harvey he sorted and put in order all the early material.

From time to time the Mitchell has acquired much of this material and, in 1978, made a very important acquisition with some special funding from the government of New South Wales. The collection consists of authors’ correspondence, manuscript material and company records and, although there is some restriction on certain documents, much of the archive is generally available to accredited readers.

A fine photograph of George Robertson came to light too late for inclusion in his grandson’s book. I looked at it in the publishing office of Robertson’s great-grandson, John Ferguson. The family likeness persists so strongly I thought of Thomas Hardy’s ‘Mine is the family face / Flesh perishes, I live on’. I doubt anyone will ever properly estimate what Australian scholarship, literature, and culture generally owes to this family.

Comments powered by CComment