- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: New Voices for young Readers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australian children’s literature has its own established heavies, writers whose work is well enough known both here and abroad, frequently in translation, and whose names would be well up in the Public Lending Right cheque lists. Some are so much in demand these days, that the time taken in preparing and giving speeches at conferences of librarians and others leaves them little time for the actual business of writing. However, they continue to dominate; each new work from them is eagerly awaited, read, reviewed and avidly discussed, if not by children then certainly by the growing adult following.

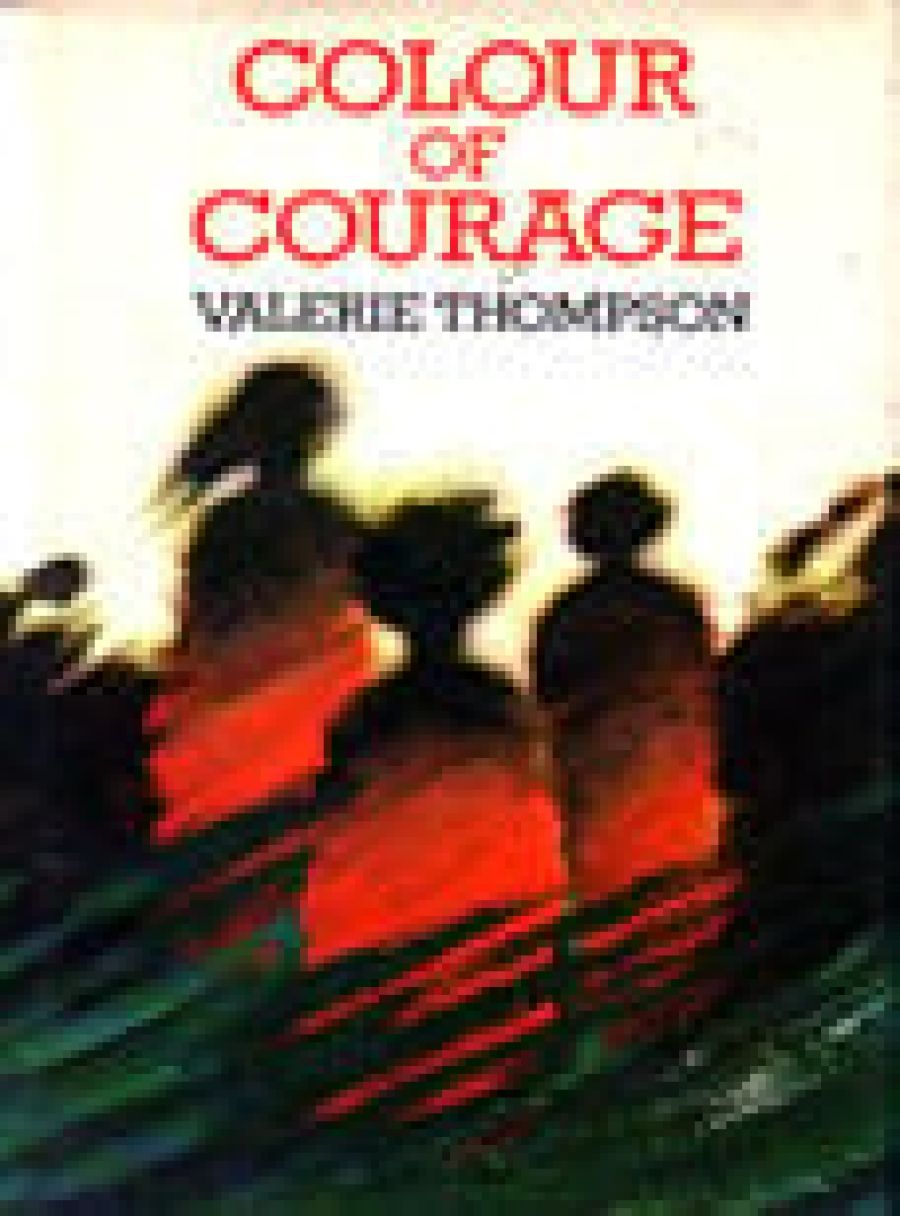

- Book 1 Title: Colour of Courage

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

These are, however, some younger, lesser-known writers whose work is good enough to get into print, being well enough written and of sufficient interest-level to be marketable. A couple of dozen books by such writers might be published in Australia in one year but few are reprinted and some of the writers are not heard of again. That was always so but one awaits in vain, it seems, for some bright new star.

Cat’s Don’t Bark (Hodder & Stoughton, $6.95, 123 pp) is a first novel by Joan Dalgleish. It is child-centred, short, easy to read, well-illustrated. It’s all about young Jeff who wants a dog for a pet but has to settle for a cat. He acquires a pampered, idiosyncratic, full-grown cat whose owner is going overseas. The aggressive and aggrieved cat gets the sulks, of course, and causes Jeff lots of trouble. The resentful cat finally comes to Jeff’s aid when the boy is threatened by the local bully – acceptance at last, and a happy ending.

The blurb calls it ‘a very true-to-life family and school story’. That’s true, but the same could be said of John and Betty (and Janet and John and all the rest of those reading-scheme inanities). Jeff has the archetypal family (a young sister and middle-class parents intact!) but he lacks a Scottie and inherits a Fluff. If it’s John and Betty told a couple decades later, it at least incorporates the sociology of the 1970s, with Mum as an actress for filmed commercials and TV series, and Jeff’s friend’s dad, who has run off. He returns at the end, for everything ends happily in this pleasant little story which has its moments but is, overall, a bit innocuous. Even so, the writing does have humour and vitality. Having arrived, Joan Dalgleish might well use her talent on something more substantial – not necessarily something more ponderous or difficult, but with stronger thematic interest.

With two modest historical novels in print (and a third on the way), Valerie Thompson has now produced Colour of Courage (Collins, $6.95, 152 pp), fifteen anecdotal accounts of courageous deeds in Australian history, such as Tom Pearce’s rescue of Eva Carmichael during the wreck of the Loch Ard. None of the heroes and heroines in this book was over eighteen years of age and not all the exploits were spectacular but, as the author says, ‘the cloak of courage comes in many colours other than the bright scarlet worn by the doer of eye-catching deeds’. The Americans produce lots of books of this type; indeed they’d have made fifteen different books out of this material. We seem more reluctant to look into our past with any sort of pride, at least on behalf of children. Colour of Courage is an excellent little book which tells its tales swiftly yet lovingly. Valerie Thompson is a writer of talent with a flair for bringing life to a history which might otherwise seem mundane.

Anne Farrell is a very young writer who has managed to stay in print. Shadow Summer (Hodder &Stoughton, $6.95, 216 pp) is her fourth book in about as many years. Living on a dairy farm in Tasmania, she chooses to write directly from her own experience of the life she knows best. Her books centre on the Mitchell family and their dairy farm called Guara. For the children, Devonport is a big town and Launceston a bustling metropolis.

Shadow Summer does not presuppose a knowledge of the earlier books although, for those readers who enjoyed them, the reunion will be reward enough. Such books could go on for years, a sort of ‘Little House in the Paddocks’ saga, especially since this life includes horses – and the appeal of horse stories for millions of insatiable pubescent girls is a well-known phenomenon.

Throughout Shadow Summer reference is made to the books of Arthur Ransome and it could be said that Anne Farrell’s style has links with that of the man who was chiefly responsible for the creation of the ‘realistic’ children’s novel – realistic in the sense of dealing with ordinary children doing and saying the ordinary things that ordinary children do. As I implied with Cats Don’t Bark, it might be questioned that children want to read about this sort of ordinariness. Ransome still has his fans but most find the ordinariness, and the inordinate detail, boring. Shadow Summer runs the risk of boring its readers with the trivia, instead of fascinating them, with its sober details about artificial insemination, milk fever, dung beetles, in-calf heifer prices and brucellosis. The author seems to record everything her characters say and do (à la Ransome) and much of it resembles Edna Everage’s incessant, pedestrian trivia. On the other hand there is enough fascination in Edna’s (or Sandy Stone’s) inconsequential preoccupations to make thousands of us fork out $15 a seat to hear it all. The same peculiar fascination will guarantee a contented readership among those children who can’t get enough of this sort of involvement.

However, having said all that about style, it must be said that in terms of content this novel is most intriguing. It is a rarity in Australian children’s literature on a number of counts. It can be read as a case study not of animal husbandry but of mental illness, schizophrenia, teenage depression or ‘nervous breakdown’, following a fall from a horse by the fourteen-year-old Lesley. Her consequent anti-social behaviour and general withdrawal leads to a sympathetic school teacher suggesting that Lesley stay at home and continue her studies through the Correspondence School in Hobart. Indeed, the book is dedicated to three of the author’s former teachers from this school.

Shadow Summer deals with the many manifestations of Lesley’s ‘breakdown’ such as her inability to tolerate noise (irritated by the voices of her teachers), even intolerance of the sound of other people eating! She interprets the overtures and behaviour of two youths as representing attempted rape. The author’s interpretation of this event is never quite clear.

Lesley’s recovery dates from an interview with a naturopath, who assures her, with advice which refutes all logical argument, ‘It’ll all be the same in a hundred years’.

Shadow Summer might go down in history as the book which, no matter how modestly, was the first to introduced matters once considered taboo. The mechanics of bovine mating, pornography and Playboy centrefolds, menstruation, mental illness and the suggestion of rape, not to mention the benefits of naturopathy, are all aired in this book. That’s a long way from pedestrian style and Edna Everage. Much of this book has so much of the ring of authority that it seems to owe more to autobiography than invention. It would never have done for Ethel Turner – or for Mary Grant Bruce, for that matter.

Finally, a note about a most unusual short story anthology, expressly designed for use in Australian schools; not only for literary ends but to help make the younger generations aware of the way in which people in the Third World actually think, and of what they think about. The editors of Stories from Three World (Heinemann, $4.95, 210 pp) say that although ‘Australian students are often told that they live in Asia’, they really know very little of what it feels like to be anything but Australian. The authors in this book come from Japan, Uruguay, Algeria, Malaysia, Kenya, China and such countries. There’s no trace of Somerset Maugham. In ‘He Took the Broom From Me’ Meakoro Opa allows Westerners to see themselves from the viewpoint of a New Guinean, for instance. The result is salutary, to say the least. My favourite is a story from Colombia by a writer named Hernando Tellez, who constructs a marvellous cat-and-mouse situation between a hated army captain and a rebel soldier-barber with a cut-throat razor. I can imagine our technical schools using it but I wonder if it will sell a single copy to one of Australia’s independent schools?

Comments powered by CComment