- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Visions in the desert

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

How, not being an anthropologist, do you set about reviewing tales and fragments of experience from Aboriginals of the Kimberleys? You might begin by stating your difficulties.

People like me can usually establish some kind of empathetic link with the arts and traditions of many cultures. If we cannot feel our way into them, at least we can derive intellectual pleasure from contemplating them: as a rule there is some point of contact, although to us, of the western heritage, nothing can ever be as real as what belongs to the family of Hellenism. I can ‘make something’ of Hindu sculpture, Inca masks, Negro jazz; perhaps even of shamanic spells.

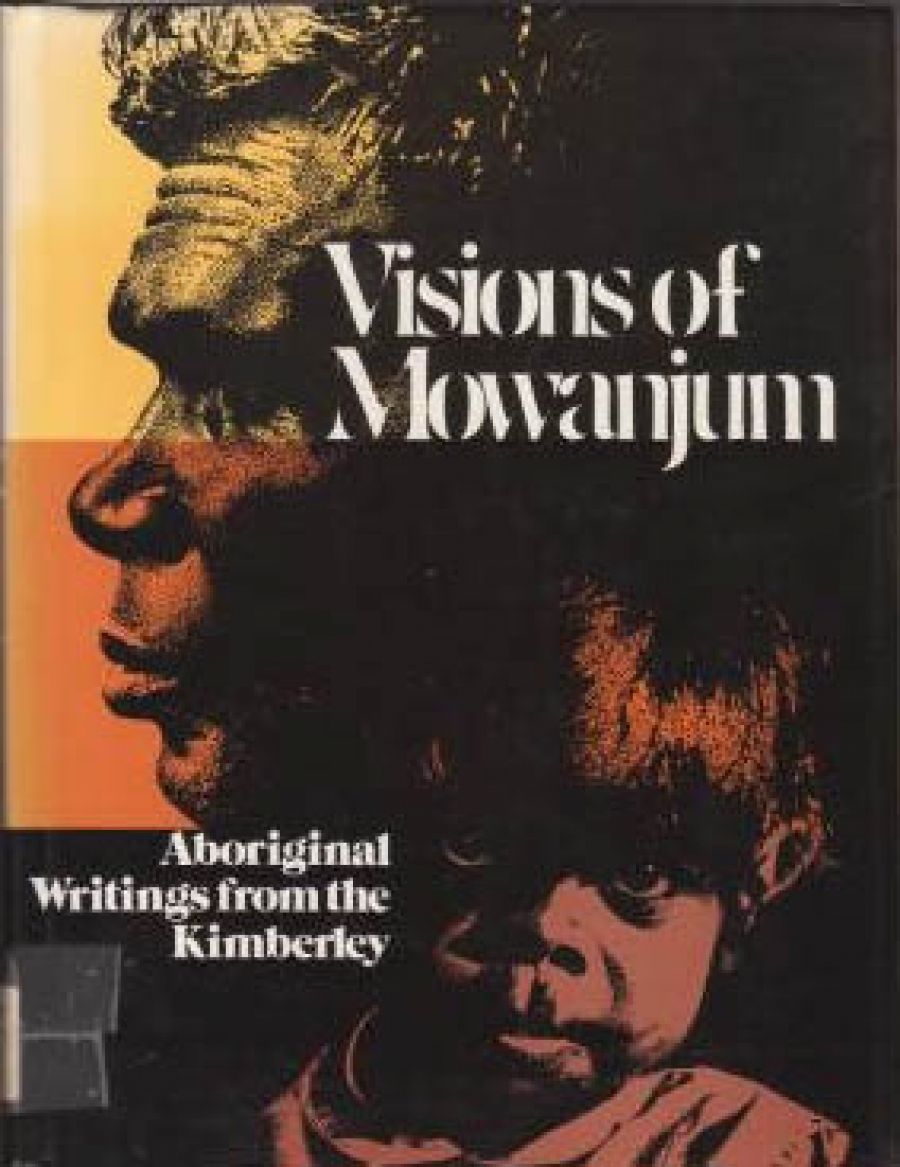

- Book 1 Title: Visions of Mowanjum

- Book 1 Subtitle: Aboriginal Writings from the Kimberley

- Book 1 Biblio: Rigby, $9.95 pb, 100 pp

Aboriginal culture is as valuable and interesting as any other but it’s hard to develop emotional links with it. And other links as well. Can one call primitive what is so highly stylised? I am not certain, but it demands too much interpretation. Until an expert points them out, can you see the goanna tracks in a bark painting? Can you really see them afterwards? See them with a recognizing eye? And is there not, defying all we are taught, a remarkable sameness about those works of art, those stories?

Of course there is, and has to be. There is no other human group that occupies so large a territory which has remained historically static for 30,000 years. The concept of change, which rules every aspect of white Australian life, was without parallel among Aboriginals until we built our cities here. Just think how different your own life is from your grandfather’s, and then try to imagine a society in which, millennia before the wheel was invented, your remotest ancestor thought, believed, acted and produced more or less exactly as did your daddy.

It is hard to think of any country where the gulf between the majority and the minority civilisation is as deep as in Australia. It is deepest of all in the field of religion. A Spirit Being is something halfway between a man and a cloud … Far easier to ‘understand’ the Great Spirit of the Sioux or of the Navajo Indians.

I have no special standpoint on the question of Aboriginal culture. I don’t know whether enough of it still survives for it to be able to flower again in the future. It is something which, I suspect, will be decided not by ‘values’ but by material circumstances – a question of numbers as much as of attitudes. If enough Aboriginals want it to live on, it probably will, and if any co-operation on our part is required it must be offered.

What little information I have seems to suggest that those Aboriginals who retain a relatively strong spiritual link with their past are happiest today in what could be called voluntary apartheid. There is all the difference in the world between enforced apartheid and the other kind: I don’t blame anyone who doesn’t want to get too close to us, or who wants firmly to control the degree of closeness which should exist.

Mawanjum (to quote this book’s excellent blurb) is a small Aboriginal community near Derby. Its people come from three tribes: the Worora, the Ngarinjin and the Wusambul, all related but each with its own specific tribal territories and sacred places. In 1951 the three tribes made history when they decided to live as one people at Wotjulum, their first united settlement. Mowanjum, to which they moved in 1956 when Wotjultim proved inadequate, was intended to be their final home. The name means ‘settled at last’.

There is far more to the coming together of these sub-tribes than this, of course. At Mowanjum there were problems with water, with employment, and so on, and in 1972 the Whitlam government helped the community to acquire a cattle station. Since 1912 Presbyterian missionaries have acted as friends and helpers, but the first baptism did not come until seventeen years later.

Mowanjum now faces all the problems every other Aboriginal community in close proximity to a white town encounters, and the resulting internal tensions are the same. The introduction discusses them frankly, if not very fully. Only the copyright acknowledgment tells me that it was written by someone called Maisie McKenzie, a quasianonymity which I don’t find helpful. But as Ms McKenzie deserves well, and my sole criticism of her interspersed biographic sketches is that they are too self-consciously laudatory. Surely, we no longer have to be reminded that Aboriginal story tellers and community leaders are warm-hearted, have dignity and pride and a sense of humour? Such positivism can be a trifle off putting.

Five people of Mowanjum, four women (one now dead) and one man, tell stories from their tribal past and from their own lives. We are not told whether they were tape-recorded and edited, or whether, as I think likely, some were written down. We learn of a young girl in a Mission dormitory who does not want to have to live with an old man, according to tradition. Why dogs must not be teased and owls must not be hurt, how a little girl strayed into the forbidden plain and how a willy-willy carried her up to the moon, how the two nightjars made the laws of marriage – and many other pleasant, charming and instructive things besides. All this is mingled with the new and the contemporary: a mother’s fear of what may happen to a son who is fond of drink, memories (albeit structured to make a tale) of Fremantle jail, and present longing for the lost days.

Many of these pieces have a certain fairy tale quality, simpler and more artless than antique myths. To me the most instructive speak of states of feeling: moods of anxiety when a friend or kinsman disappears, and how apprehension is felt in various parts of the body. I also very much like the story of two suns, mother sun and daughter sun. The oneness of nature – plants, animals: people – is always expressed; I doubt it comes out so strongly in any other tradition.

It is far from insultingly meant when I say that children and young people will especially enjoy Visions of Mowanjum. After all, so much in it dates back, in one way or another, to the dreaming, the time when humankind itself was young. Maybe this is the best such books can give us: a sense – but how difficult to realise within oneself! that our great, enterprising, progressive and geriatric world may touch, however fleetingly, the youth of our species.

Visions of Mowanjum is handsomely but not lavishly got up. The illustrations are good. The publisher and the Aboriginal Arts Board deserve praise.

Comments powered by CComment