- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Radical sensationalism without economics

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A gap of eight years is a big slice in a writer’s life: at the end, a changed man speaks in a different context. Al McCoy’s Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia (1972) and his Drug Traffic: Narcotics and Organized Crime in Australia (1980) have the same publisher and the same villain, but they are very different books.

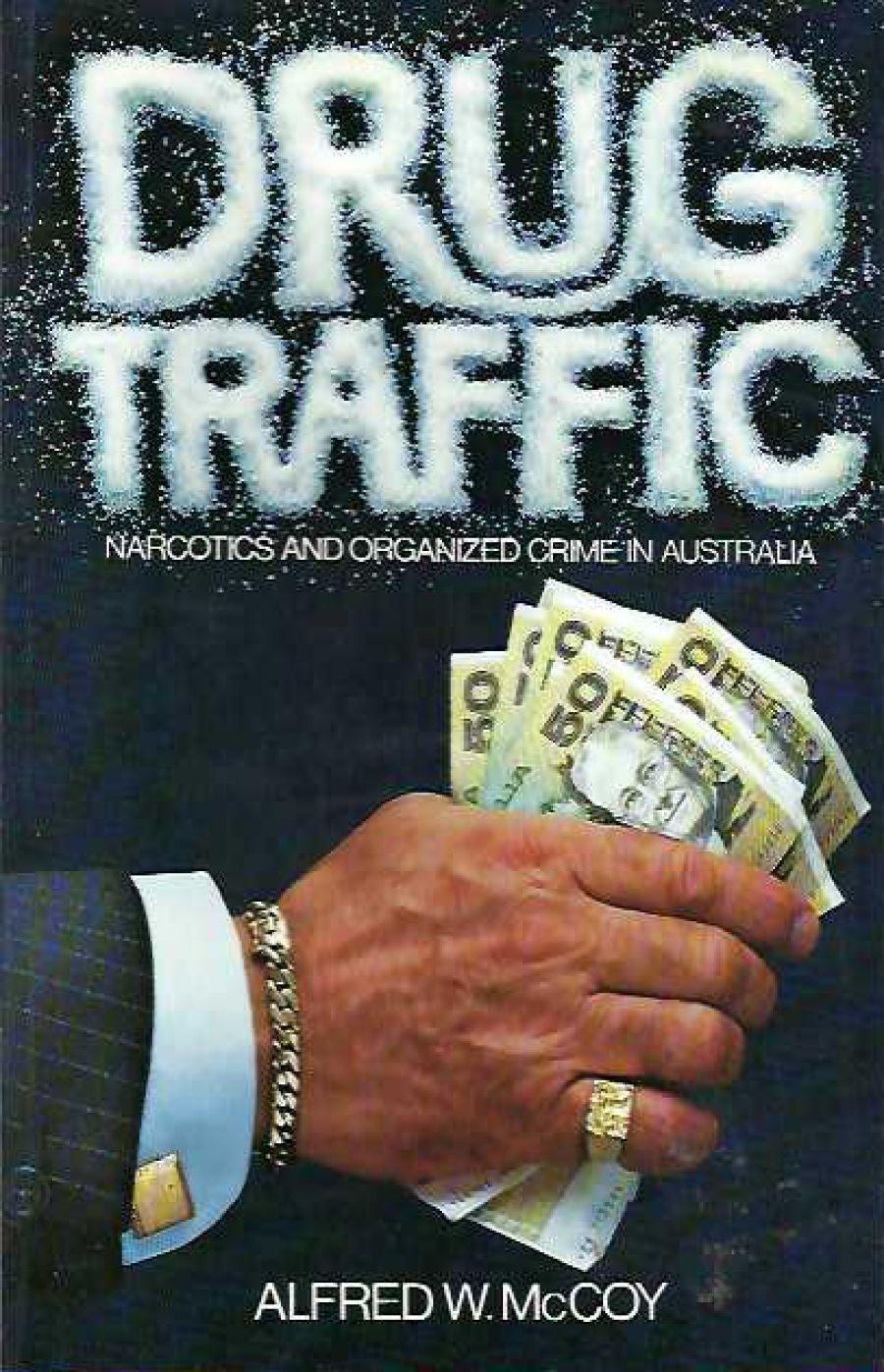

- Book 1 Title: Drug Traffic, narcotics and organized crime in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Harper and Row, $9.85, 455 pp

The product, Drug Traffic, runs to some 175,000 words. Nearly a quarter is given over to the history of drugs all sorts, including coffee and tea, though not Coca-Cola, and we are virtually halfway through before reaching the end of World War II. By then, McCoy’s ‘Australia’ is rapidly shrinking from Victoria and New South Wales to Sydney, where he now lives, and Griffith: Brisbane is confined to one page only.

The book doesn’t lack freshness altogether. McCoy has written a short chapter on the politics of the Golden Triangle. the source of our heroin, which brings us up to date: located unpublicised court transcripts, relating to the trafficking of the younger Moylans, the heirs to Sydney’s ‘33 Club’, who went into drugs after being driven out of gambling; and put together two profiles, of a predatory pusher and a sensitive addict. He shows commendably little mercy for Mr Justice Woodward’s 1979 Report, which coincidentally plagiarised a paragraph from McCoy’s earlier book.

But the bulk of Drug Traffic relies on newspaper items and official reports. It asks to be judged on the accuracy, selection and critical evaluation of these sources, the plausibility of its inferences and the adequacy of its overall interpretation.

One Sydney-sider’s confidence was shaken at the first reading. What was I to make of the statement that Sydney’s casinos in the 1960s were ‘the equal of Europe’s finest’ (p.194)? The most conspicuous, at Rozelle, was on top of a shoe shop, none had parking facilities, most had the narrowest of doors, and only one, at Potts Point, had external signs of affluence! Who would think of describing a marginal fall guy like Bela Csidei as ‘the prominent Sydney businessman’? Who, having read Daphne Colbourne’s series of articles, My 10,000 Abortions, would believe that organised crime leaders waited until 1967–68 to move in on the abortion racket? Having read Colbourne’s testimony on the senior police officer she refers to as ‘The Collector’ (he’s now dead), who would depict him as a goodie in another context? And with the Nugan Hand bank collapsing while this book was being processed, who would allow the description ‘the fastest growing finance house in Australia’ to stay in the galleys?

McCoy doesn’t only get the nuances wrong; he frequently mixes a heavy dash of black pigment into the colours for effect. For instance, using an estimate of the weekly ‘gross profit’ of the Double Bay Bridge Club (an illegal casino) of between $30,000 and $60,000, and ‘operating expenses’ of $16,000 a week, McCoy arrives at annual ‘profits’ of $2.3 million. That’s using the top figure, as if it were the only one.

What is the thesis which such details are made to support?

According to McCoy, Australia is in the midst of a heroin plague, the result not only of a reliable source of supply but also of a potential group of customers prepared to demand it by more than a century’s consumption of other drugs. The public has long tolerated some sort of organised crime, there is a modicum of established police corruption, and an informal alliance between drug syndicates and influential politicians and administrators has now been forged. These are the preconditions; but why heroin? It ‘enjoys the highest profit margin and quickest cash turnover of any economic enterprise known to man’.

An innovative form of economic analysis, for sure. In the several forms of economic thinking, mainstream, radical, Marxist, prices and profits are never determined by the physiological qualities of the commodity, even if transport costs, based on the physical form as one factor, Drug Traffic, showing a hand clasping a bundle of fifty dollar notes, suggests that the gook might tell us such elementary things: it doesn’t.

Some readers might regard this book as an invitation to the trade; others, as a plea for desperate measures. McCoy gives no explicit recipe for stopping the traffic but he paints an admiring picture of President Marcos giving a personal order, shortly after the proclamation of martial law in the Philippines, to shoot a heroin manufacturer who had been condemned to life imprisonment under due process.

I have little doubt that heroin trafficking appears highly profitable to those who rush into it. It probably yields far too much to its organisers after they meet their overheads. I have a hunch that in addition to any money which Sydney’s traditional ‘crime syndicates’ may have might constitute a bottom limit to the equilibrium price in a given market. And those unique profits are all the more puzzling because only a tiny fraction of the potential supply reaches Australia.

McCoy has discovered some equally novel accountancy concepts, which blur the distinctions hitherto made between mark-up and profit: ‘Rising from a cost of about $2,200 for a kilogram in Bangkok to $230,000 when adulterated and packaged in the streets of Sydney, heroin enjoys a 100-fold margin of profit which leaves more than ample cash reserves for the acquisition of allies among the police and government.’ A less innovative accountant would distinguish between mark-ups and profits and include pay-offs, couriers, fees, plane fares, legal costs, dumpings, seizures and the fees of hitmen before profit. And that dull professional, far from personifying heroin, would want to know through which hands the stuff and the money passes, and who keeps the largest bundle of banknotes. The picture on the cover of raised, there’s plenty of the smart money flowing into the trade. A part of the remedy is to increase the overheads; for instance, by imposing monetary fines concurrent with jail sentences, at a rate of five times the street value of the heroin seized. Such fines would bankrupt the smaller fry, and the bankruptcy proceedings, apart from making the underlings sing, might open up new areas of investigation. Before going into the merits of this suggestion, we would need much better estimates of the real profits in the trade, and of who takes them. Street peddlers and couriers apart, the pursuit of profit is its aim and essence. It is the root which needs to be attacked. Radicalism without economics is a sham. It is likely to end up, like other purported radicalisms in search of purity, with leaders cashing their blank cheques and turning out the firing squads at dawn.

Comments powered by CComment