- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The University of Oppression

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

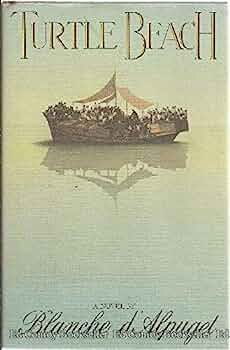

Dust jacket blurbs are usually misleading, but at least one point made by the back cover of Blanche d’Alpuget’s new novel, Turtle Beach, is authentic. It refers to the ‘Graham Greene sense of inevitability’ of the events of the work. As an admirer of Greene, especially in his Third World novels, I can confidently recommend Turtle Beach as a worthy successor to such socially important novels as The Quiet American and The Comedians. D’Alpuget has the same keen sense of the inadequacies, irrelevance and wrongheadedness of Western involvement in the East, the same wryly ironic depiction of the frailty of human nature regardless of class, colour, creed or sex.

- Book 1 Title: Turtle Beach

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $ 3.95 pb, 287 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Judith Wilkes, ex-convent girl, successful journalist, mother of two sons and the wife of the politically ambitious Richard, has first come to Malaysia to cover the race riots of 1969. After ten years of bored and frustrated Canberra life, she returns to Malaysia to report on the landings of the Vietnamese boat people, the human flotsam of that disastrous war, whom no one wants and who are ruthlessly exploited by diplomats, officials, police, the local villagers, sea-captains, and ultimately, of course, Judith herself. In Malaysia she stays with her old school colleague, Sacha Hamilton, and then with Sir Adrian and Minou Hobday. Through Ralph Hamilton and especially Minoushe, she gains access to the deplorable camps of the Vietnamese, the tawdry society of Anglophiles, be they Indian, Chinese or Australian in K.L, and the incomprehensible rituals of Hindu.

Ultimately the novel is about oppression. There is the personal subjugation of women by men, of women by their own internalised masochism, of Hindus and Chinese by Malays, of the East by the West. Judith’s sexual response is used as a sort of index of her subservience, firstly to Richard, later to Kanan. None of the relationships in the novel is permitted happiness; few even have the pretence of love. D’ Alpuget’s ironic yet compassionate eye sees all too clearly that sexual, emotional, religious and cultural exploitation share common roots and that each is totally destructive of personal integrity and psychic wellbeing.

Minou does escape, but at the price of her own life. She attains through suicide the dignity denied her as refugee, sexual toy, breaker of social taboos. Judith’s future is not so clear for although she grows in personal integrity and strength – er shunning of Kanan makes this , clear – the concluding pages of the novel suggest that with return to the blandishments of Australia and fame she will cast off any such awareness. I suspect that Blanche d’Alpuget is too astute an observer of humanity, and women in particular, to suggest that entrenched ways of thinking and seeing can be abandoned, even amid the horrors and enlightenments of such a cultural melting pot as Malaysia. Judith may make the decision to gain custody of her children, or her home, and there’s the rub; she does not attain the ‘atonement’ with herself, her sexuality or her lifestyle which is early advised by the kindly old Catholic priest.

As an aside it is refreshing to have an author deal with Catholicism without the convenient ‘out’ of blaming the church for sexual hangups. Judith does try it, but is honest enough to realise that her sexual distaste for Richard is due to a host of reasons far more complicated than the teachings of church and nuns. Yet she is not honest enough to admit the truth of the priest’s plea for reconciliation of the self but takes the customary and much personally safer course of ridicule and disparagement.

Turtle Beach is a fascinating novel. It is well written and nowhere strains for ‘significance’; by not doing so it achieves a great deal. Its examination of the interrelationship between the personal and the political, the universality of oppression, the malaise of bigotry and intolerance which blights us all makes it a highly relevant and important social commentary. d’Alpuget’s evocation of peoples and locale, be it of Canberra diplomats or refugee camps or Hindu festivals, is immediate and vivid. Rather than comparing her with Graham Greene perhaps we should look back to some of our unsung Australian social realist writers like Dark, Cusack and Tennant. Like them Blanche d’Alpuget sees that the oppression of women by men and by themselves is but one facet of a general human dilemma.

Comments powered by CComment