- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Native Motifs

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

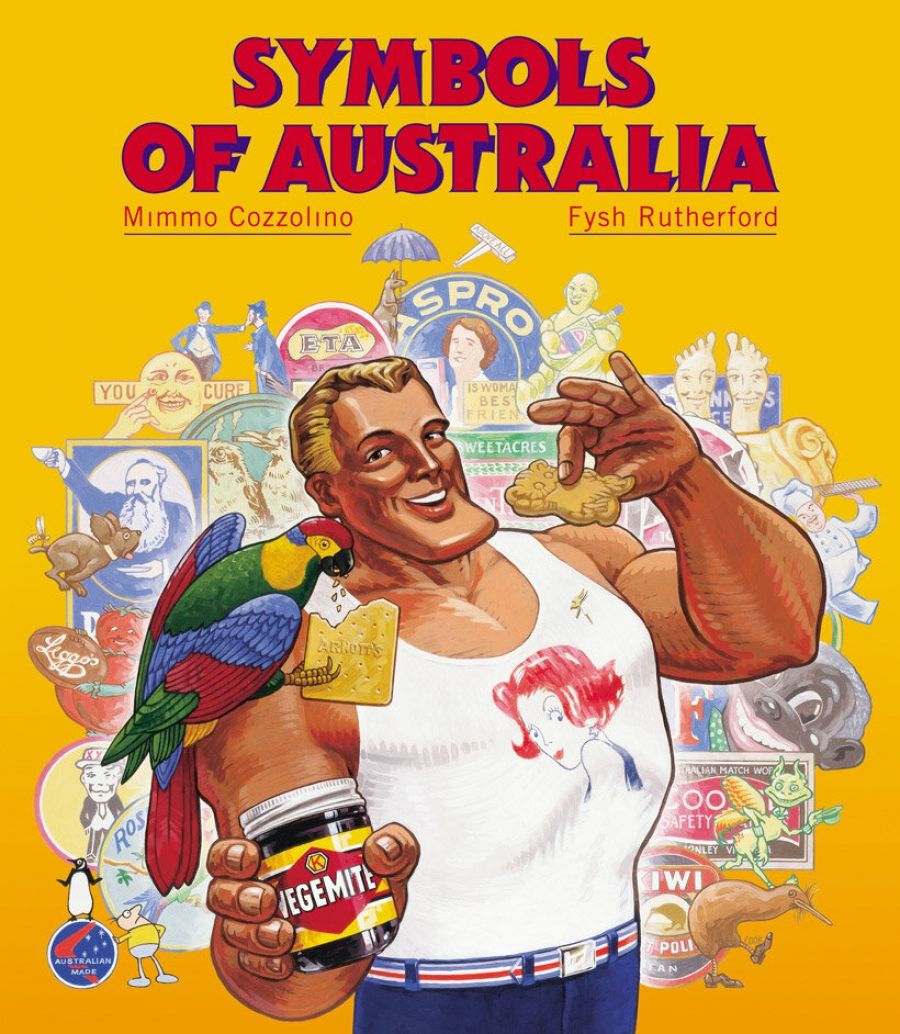

Following the enterprising publication of Michael Leunig’s drawings and of Arthur Horner’s ‘Colonel Pewter’ and ‘Uriel’ cartoons Penguin’s latest offering in illustrated publishing in a wonderful book of evocations – a selection of many hundred Australia ‘trademark’ symbols created to identify local products ranging across the one hundred years from 1860.

Symbols of Australia is essentially a picture book. It has no conventional text apart from the introductions and preliminary notes, but there are captions which attempt to date the examples and sometimes explain their history significance.

- Book 1 Title: Symbols of Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, 192pp, $9.95pb

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

With the passing of time and the invention of the steam-powered engine and the subsequent manufactured consumer products of the Industrial Revolution, the need for identification on packaging resulted in the printed ‘trademark’ as we know it today.

The first ‘mark’ or symbol to be recognised in Australia by the arrival of the First Fleet. This was the ‘broad arrow’ commonly associated with identifying the clothing of convicts, but with wider uses to mark any of His Majesty’s Government property. The symbol survives today on Australian Army equipment.

Although most of the designers of Australian trade marks are anonymous, it is known that Blamire Young, the lyric painter of Australian landscapes, with Percy Leason the supreme pen and ink draughtsman famous for his Bulletin drawings, and Norman Lindsay when a student in Melbourne – all worked designing and drawing with big printing houses producing labels or posters or trademarks – whatever came along.

The period when Lindsay, Leason, and Young were studying their art was a time in our history when an Australian national identity was emerging, when ties with ‘Mother England’ were for the first time, being challenged. And when the dashing reputation of Australian soldiers during World War I, particularly after Gallipoli – an event itself giving rise to a trademark – it was generally regarded at the time Australia had come of age, had in fact achieved nationhood.

It is not surprising then to see native motifs, rather than the exotic, used with pride in the decorative arts. Waratah, wattle and gumnuts were among the subjects for moulded plaster in homes as were the magpie, kookaburra, cockatoo and the swagman for leadlight stained-glass windows. Put to a wider use, indigenous flora, fauna and unique Australiana which included Aborigines, the Southern Cross, famous landmarks and institutions became in their day familiar emblems as trademarks on products in every Australian household; indeed, some have survived in a re-styled version to the present time.

Australians trademarks had their beginnings during the Victorian era when strict naturalism in all the graphic arts was the rule – echoed too in corporate and municipal Heraldry which broke with tradition to introduce naturalistic palm trees, whales, sailing ships and other awkward objects into badges, seals and coats of arms – the whole pictured in natural colors and shapes, later defined by the Heraldic term ‘proper’. The totally discarded tradition of depicting stylized objects, set by the Medieval designers, was replaced in favour of images for trademarks in three-dimensional naturalism in as far as the skill of the artist would permit. These seemingly complicated and often grotesque representations were at odds with the beautifully designed and cleverly stylised trademark motifs prepared for metal stencils to brand containers like sacks and bags.

The naivety of the early Australian trademark with anthropomorphic tomatoes and lemons, smiling feet, and cigarette-smoking kookaburras display a winning charm and often a humour, all so different from today’s clinical sophisticated ‘logos’ and ‘corporate’ symbols.

Celebrated here then are examples of Australian trademarks which, although from an era more innocent and less complicated than our own, are nevertheless significant as an important expression of a period where Australia was, with pride, emerging as a nation, and in that process characteristics were formulated reflecting among other traits a home-made slang, a strident racism, hairy-chested chauvinism and an unbelievable naivety, all of them echoed in these graphic symbols.

Mimmo Cozzolino is to be congratulated for his originality, dogged researched and significant contribution to the too few studies of Australian popular culture. In his introduction Geoffrey Blainey, too, adds much to our knowledge of the subject – which is more than can be said for the painful puns and clips from the autobiography of Philip Adams. The space reserved for his co-introduction would have been more importantly occupied with a couple of notable symbol omissions – ‘Willie Weeties’ (King of Breakfast Foods) from the 1930s and that famous peddler of linseeds products – Meggitt’s ‘Little Boy from Manly’.

Comments powered by CComment