- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Making Australia

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Although Howard Florey spent most of his life abroad, he was a great Australian and according to his biographer probably the most effective medical scientist since Joseph Lister.

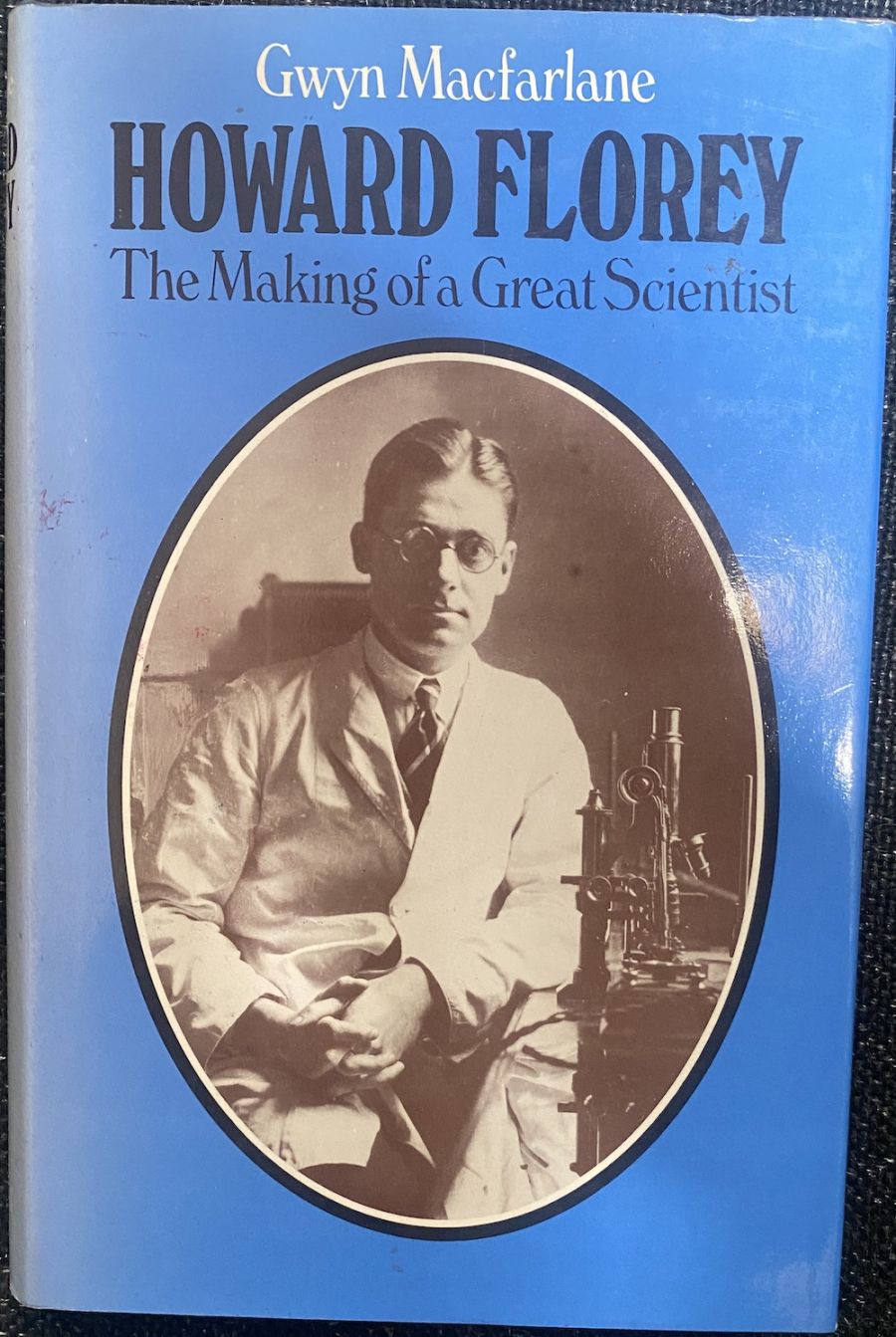

- Book 1 Title: Howard Florey

- Book 1 Subtitle: The making of a great scientist

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, $26.00 pb, 396 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Florey’s best known achievement was his role in the development of penicillin. In that role his outstanding personal and professional qualities combined to earn for him a Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine in 1945. Foremost of those qualities, according to his closest contemporaries was that of being ‘a great finisher’. The history of science is strewn with unfinished promising experiments. Florey could and invariably did get down to a job quickly and stay with it until completion. Throughout his life, he was scrupulously honest in his scientific approach. He employed first-rate techniques in a prodigious manner and established sound factual bases which subsequent investigators could not afford to ignore.

It is not entirely surprising that his energy and enthusiasm for work were accompanied by an intolerance of people with whom he shared little or no interest. He was not one to engage in small talk. Productive conversation he sought, with philosophy being his least popular subject. His biographer, on the other hand, who knew him well for over two decades considered him ‘affable, considerate, and in his peculiarly astringent way, amusing’.

Florey’s biographer traces the development of penicillin in an exciting and lucid manner which dispels much of the mythology still attaching to the development of that ‘near-perfect chemotherapeutic agent’. The groundwork was laid by Fleming, who discovered penicillin in 1929, but produced it in a form suitable for limited use as a local application, notably for eye infections. For over a decade it remained neglected, awaiting the energy and direction necessary to promote penicillin antibiotic therapy. During that fallow period, Florey as head of the William Dunn School of Pathology at Oxford built up a team of scientific workers capable of such development.

Professor MacFarlane doesn’t neglect Florey’s ‘warts’. There is evidence of his snobbishness and touches of intolerance as, for example, in his disparagement of Jews and Italians whom he apparently encountered en masse during his first visit to New York in 1925.

Several issues touched on are relevant to the contemporary Australian scene. The importance of supporting basic scientific research is one. So is the important interface between science and industry – the near-heartbreaking experience of commercial reluctance to promote penicillin development holds several lessons. Another is the need, as Florey saw it, to disregard the traditional yet artificial boundaries separating scientific disciplines.

Howard Florey remained an Australian while benefiting from much that Britain had to offer. His career flourished at a time when it was thought that the gifted Australian scientist had to go abroad to fulfil his potential. The reader may well ponder whether Australia today has advanced much beyond that point and whether conditions here are sufficiently conducive to the development of other Floreys.

Comments powered by CComment