- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mine is the Family Face

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A colleague questioned my choice of these two books for this page, wondering whether they are too localised for a national journal. This reminded me of a Victorian friend who once aired a theory that the poetry of Kenneth Slessor. That man of Sydney, is not highly regarded in Victoria while ‘Furnley Maurice’ (Frank Wilmot) is little appreciated north of the Murray. What rubbish. Admittedly a writer’s presence on his own soil can be important both for his work and, in some ways, for his audience. It was only when Patrick White and Christina Stead returned to Australia after long absences overseas that they gained proper honour here. But universality also cuts across boundaries and there are universal qualities, or at least for ‘new world’ countries, in each of these books.

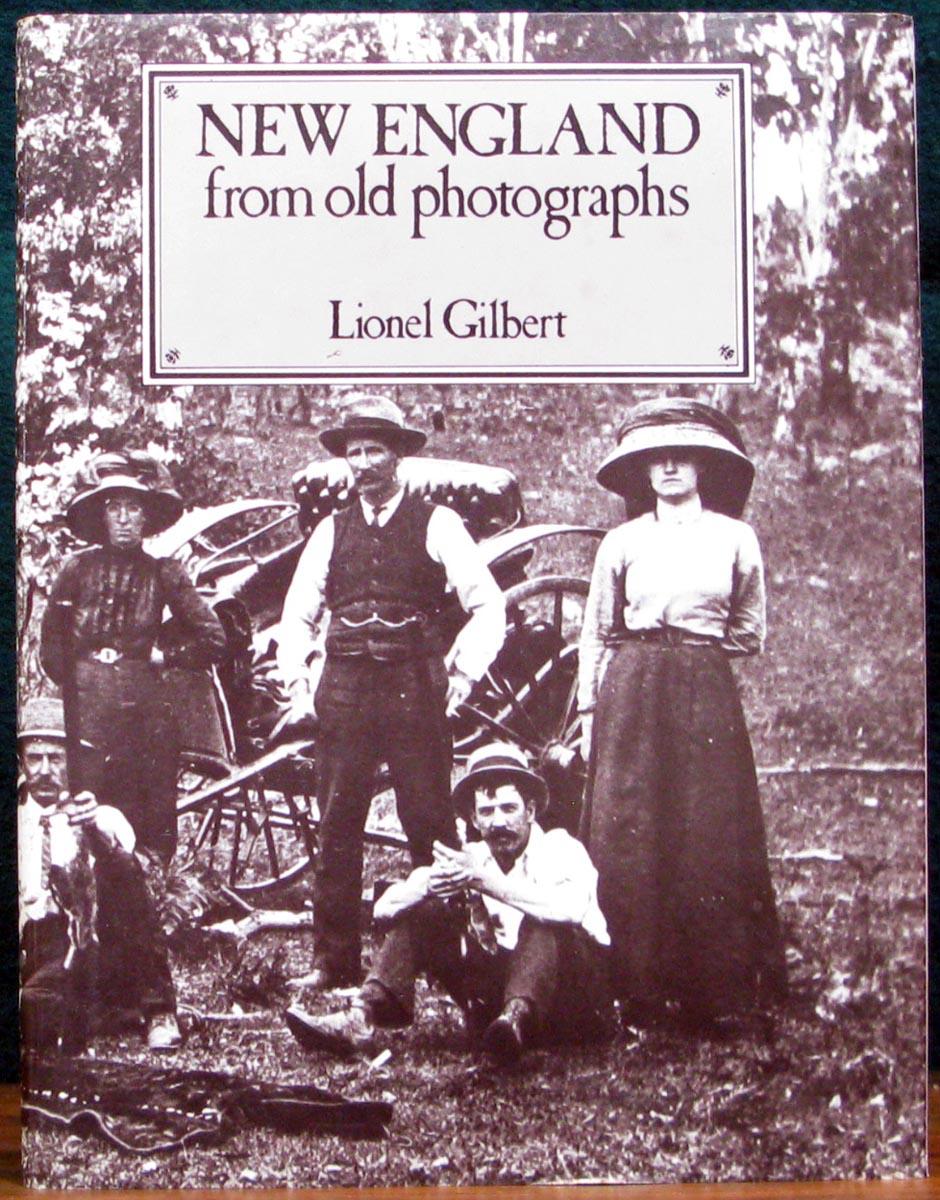

- Book 1 Title: New England from Old Photographs

- Book 1 Biblio: John Ferguson, $14.95 pb, 144 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

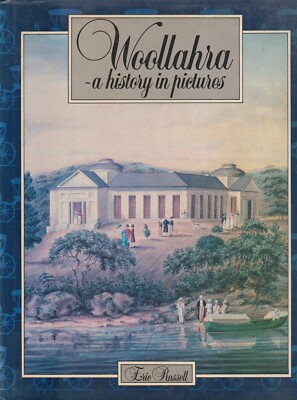

- Book 2 Title: Woollahra

- Book 2 Subtitle: A history in pictures

- Book 2 Biblio: John Ferguson, $12.95 pb, 158 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

When Judith Wright’s early poetry of her New England heritage appeared, (and that, be it remembered, was first published by Clem Christesen in Meanjin Papers in Queensland) its impact was immediate, exhilarating and Australia wide. The pictures and excellent captions in Lionel Gilbert’s book record some of the history, landscape and people of ‘that tableland, high delicate outline/of bony slopes wincing under the winter,/low- trees blue-leaved and olive, outcropping granite – clean, lean, hungry country ...’ Maybe among the faces of black and white New Englanders are the forebears of the Half-Caste Girl – ‘little Josie buried under the bright moon’.

Gilbert’s selection is not just old photographs. Every one of them is a reminder or discovery and no discovery is more surprising than the 1903 group portrait of the 2nd Armidale Ladies’ Fire Brigade whose captain Minnie Webb, at the centre of her team of nine neatly uniformed young women, was a nurse. One of today’s cliches is the scarcity and paucity of historical records of Australian women. Admittedly written material is often scant but volumes can be inferred from a book like this. Who made the military outfit for a little boy fund raiser, of some four or five years, during the first world war? Chapters of history speak from that picture alone. Behind the wedding cake photographed on page 135 and on the opposite page the tables elaborately dressed in a church hall for the St John’s Mothers’ Union anniversary dinner in 1910, are a dozen tales of art and pride and effort among the smoke of fuel ranges, the difficulties of no refrigeration, fly-wire screens or insect sprays of women always dressed in corsets, petticoats, long skirts, thick stockings, starched collars and aprons no matter how high the mercury.

In early photographs of aborigines and the settlers superseding them are faces of today. ‘Mine is the family face’, wrote Thomas Hardy, ‘Flesh perishes, I live on ... the eternal thing in man/that heeds no call to die’. Well, from a Church of England choir of 1900 stares the spit and image of an Italian girl I know. That recognition sets me pondering the seminal legacies of armies over-running Europe for centuries. What mischievous nonsense racist beliefs and assertions are.

The growth of suburbs and their services – transport, shopping centres, schools and hospitals – was surprisingly similar across the continent. Every region is unique, and yet paradoxically much the same. The Municipality of Woollahra covers a large area from Watson’s Bay at the South Head of Sydney Harbour to Paddington which abuts on Darlinghurst near the centre of the city today. Within Woollahra are clustered settlements of great variety and miles and miles of harbour beaches, bays and headlands. Parts of the municipality have always been fashionable, from the earliest mansions to the latest luxury units. Others, like Paddington, have come the Australian circle from fashionable to seedy – sometimes slum – and back again to high desirability.

This is the part of Sydney I learned through the wheels of my pram and the soles of my shoes. I was born directly opposite St Mark’s rectory in Darling Point Road. An aunt and two grandmothers lived nearby. By Breakneck Steps, an area of much interest in Russell’s book, (which is in fact Marathon Steps but no one then or now uses its correct name), or Jacob’s Ladder, another old stairway, we clambered to and from Double Bay to fish or swim. We trammed out to Watson's Bay to swim or fish and to ponder suicide and mutability and shipwreck at the wild, magnificent cliffs of The Gap. We endured the disgustingly filthy water (sharks would have been almost preferable) of Rushcutter’s Bay and Rose Bay baths – the former were taboo for women at certain hours when gents might wear trunks. Then someone suspected the connection between sewage and polio and compulsory school swimming moved to more salubrious locations.

We knew most of the mansions so magnificently photographed here from the outside, and many from the inside because family friends and relations were ubiquitous in the area. Indeed one of the worst features of a childhood in such proud suburbs – they always were, read the book – was the omnipresence of tattle-tale adults. Let a child from a treehouse drop wild-olive berries onto a hat brim below, or tease her younger sister in a back lane, or use a naughty word to a naughty dog, someone was sure to see or hear and report the offence.

Eric Russell has perforce been selective, leaving material for a sequel, or sequels, let us hope. He is rather light on the schools of Woollahra which, both private and state, are interesting. Some are built round nuclei of historic buildings, others like Double Bay primary, continue in an original building that has become historic. On the other hand Russell is marvellous about transport: ferries and their disasters and trams from the first cable cars to the final corridor types which inspired my father to ask: ‘Why are Double Bay trams like bananas?’ and answer: ‘Because they’re green and yellow and come in bunches’. And so they did after irate intending passengers fumed for up to ten minutes at the Darling Point stop, and sighed for the good old days, and watched beautiful mad Bea Miles hopping onto the horizontal bonnets and running boards of passing cars, or Mr Allen of Allen, Allen & Hemsley driving sedately past at about fifteen m.p.h. in his gleaming electric brougham.

Darling Point was a great place for snobs and toffs though not all the toffs were snobs or vice versa, and some citizens were both. Woollahra was also a great place for Leaders of the Law (one judge with a monocle) and for early writers and feminists. Some writers like Henry Lawson and Henry Kendall only came there after death to remain in famous cemeteries under ornate memorials that mock the poverty and despair of their lives.

Blanche Mitchell, the diarist, and her father. Sir Thomas, may have been the earliest writers. A few years later there was Sir John Hennicker Heaton whose Dictionary of Dates and Men of the Time must be one of the most infuriating books in the whole world because of its madly disordered non-arrangement. There is a strange photograph on page 104 of Dorothea Mackellar resembling a teenage hippie circa 1970 en route to the wide brown land bare-footed and carrying what may be a rucksack, her long hair streaming. Since it was 1917 and she about thirty-two, perhaps amateur theatricals explain the gear. On an opposite page G. Nesta Griffiths, chronicler of Point Piper, looks fetching in swathes of silk and clouds of chiffon. No photograph of Christina Stead who is indisputably the immortaliser of Watson’s Bay.

Rose Scott, social reformer and suffragist has a fine strong face. Lady Jessie Street was snapped in a happy moment. Ruby Rich Schalit, the feminist survivor of that era, now in her nineties, still lives in Woollabra.

Ah Paddo! Louis Stone’s Betty Wayside could find her way yet around its streets and recognise familiar buildings despite their predominantly frost-white restoration. She and I and Eric Russell, and Sali Herman who painted Paddington memorably, were more familiar with dark brown, cream and green paint. These are precisely the colours now slapped on recently restored buildings all over Sydney. Next time round my bet is that Paddington will revert.

An interesting section of the book shows early posters for land sales. Unfortunately they are reproduced too small for adequate exploration even with a strong magnifying glass. More and larger next book, please.

Woollahra was gazetted a municipality after many of its leading citizens petitioned for local government in 1859, and proclaimed in 1860 at about the time Blanche Mitchell’s straying family cow was found grazing there. Thirty years later as one can see in this book the more desirable land from the Heads to Rushcutter’s Bay was built on, often quite densely. Maybe by then the waterfall at Darling Point had already vanished. Frank Fowler described it in Southern Lights and Shadows (1859) and since Fowler is not quoted by Russell I give him the final word. He took a sixpenny omnibus out to Darling Point and admired St Mark’s church (an Edmund Blackett building) ‘A perfect toy of a church, and sits as plumpy on its stone mound, as a castle, done in white sugar, on a twelfth-cake’.

Then there were the ‘Dripping Rocks’ where you could stand under ‘overhanging ledges, and see the bright water falling just in front of you – sparkling in the sun, like a curtain of crystals’ while from a distance it was a ‘brilliant cascade’ that ‘flashed out its thousand little snaky jets of rainbow’. Nearby he admired the many specimens and varieties of fern, and gathered five or six of them. Buried somewhere beneath the American consulate’s enormous 1930s pile, I suspect.

But no one can solve the Keesing family puzzle. Every so often, in our garden, the spade would turn up a George III penny. Who dropped them? Some old ghosts rightly keep their secrets.

Comments powered by CComment