- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: His Stage was the World

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Playwright Christopher Fry long ago wrote that ‘The bridge by which we cross from tragedy to comedy and back again is precarious ... if characters were not prepared for tragedy there would be no comedy ... their hearts must be as determined as the phoenix ... what burns must also light and renew’.

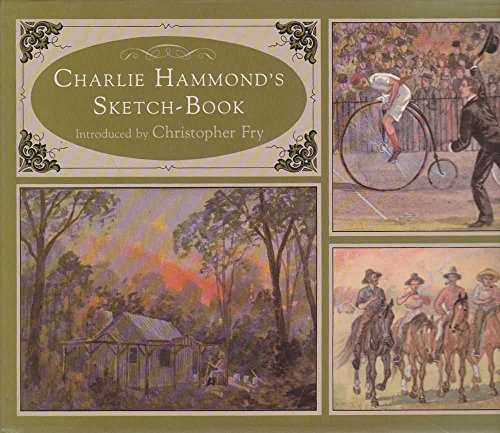

- Book 1 Title: Charlie Hammond’s Sketchbook

- Book 1 Biblio: OUP, $15.95 pb, 78 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Fry hardly remembered his uncle Charlie, who passed in and out of the lives of his relatives with a certain aura of mystery. His stage was the world, although his own role was not much more than of a bit player. He was a natural, to begin with, and he managed to cross from comedy to tragedy and back again during the sixty years he sketched the events of his life, much of it spent in Australia. It was a life combining failure and success, gregariousness and contemplation, and there were enough moments of drama to make one believe he could have been a character in one of his nephew’s plays.

Together with Charlie’s artistic cooperation and ‘honest captions, Fry has provided an unpretentious text, tightly packed with just enough significant details to answer all the questions one needs to know about the family background and Charlie in particular. The result is a rich little tapestry in which many strands have been drawn together. Here strut neither vapid members of high colonial society nor wily politicians; no bushrangers, rebels or explorers; no deathless heroes or bible-banging reformists. The experiences of any of the characters might have been those of perhaps half the population in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Charlie himself evolves as a latterday S.T. Gill, a regular mate, with a touch of Lawson and Furphy thrown in for good measure.

How splendid it is to see the sketches reproduced in such a manner that the tattered edges, mostly buff or flesh in tone, are seen against soft green borders, from olive to sage. The publisher has mercifully left them untrimmed and presumably in their original sizes, which must have created technical difficulties as well as occasional chronological problems. However, one wishes that the album had been a little larger to provide easier reading of Charlie’s amusing and informative comments. This reviewer found them quite difficult to read by night light. Although not credited with the design, it would appear that Fry himself had a hand in it, for his sense of the theatrical and his own flair for interrelating events to give the appearance of an organic whole, are evident. He has managed to arouse a sense of excitement, of wonder, in the reader. One readily becomes involved with both the simple pleasures and the more adventurous exploits of the incorrigible Uncle Charlie.

Born 1870 in London, Charlie Hammond had had a comfortable and secure early life as the eighth child in a ‘moderately prosperous’ middle-class household somewhat influenced by his mother’s Quaker background. She was a Fry and the ninth child was Christopher’s mother, later married to a Harris. Charlie had shown some artistic talent from childhood. His earliest sketches portray a life of gentility and tranquility, of croquet, cricket, skating, and cycling; of receiving prizes at school, dabbling in photography, feeding the family pets and generally enjoying festivities at Christmas time.

But these times were not to last forever. Charlie’s father. Rowland Hammond, suddenly packed himself up and left the family for Australia. Other members set out for Canada and New Zealand. At the age of fifteen Charlie also left home, which by this time was at St. Mary's Fields, Leicester, where his mother had gone to live with her sister. Charlie first went to New Zealand to visit two married sisters, took various office jobs there, then became a cabin-boy on a ship which took him to Melbourne. By this time he was in demand as a caricaturist.

In Melbourne he met up with his brother Bert who was working as an interior decorator. Charlie soon afterwards joined an American ship, the Great Admiral, by which he returned to England via Hong Kong. Some of the more dramatic sketches in the album depict a thunderstorm at sea, the shanghaiing of a crew, fights with drugged sailors, and a mutiny at sea.

Back in England he returned to the ease and pleasantries of country life at St. Mary’s Fields. During this otherwise blissful year, in which he became apprenticed to a farmer, his mother died. Soon afterwards a call from Bertie to rejoin him in Melbourne re-awakened the wanderlust and he worked his way as a steward on the Riverina, arriving back in Melbourne in October 1889. Another brother, Hal, came from Canada to settle with them in a bungalow in Malvern, which they named Bachelors’ Hall.

Charlie and Bert began to earn a little from photography as well as painting. They produced the first negatives of jumping races taken in Melbourne and there are sketches of the Melbourne Cup of 1889, in which Carbine ran a place, races at Caulfield, trips to Fern Tree Gully, Healesville and comic strips of camp life. But misfortune was soon to strike, firstly with the theft of their cameras and other valuables, but more seriously with the collapse of the land boom in 1892 and the depression which followed.

Charlie went farming in the Western Port area and recorded his experiences there, getting ‘a lot of fun out of life in spite of hard times’. He revisited relatives in New Zealand but there was no lasting work for him there and he returned to Sydney where he helped decorate the interior of ‘the Sydney Cathedral’, which appears to have been St. Mary’s. He undertook some studies at the Sydney School of Arts, after which he returned to Bert in Melbourne in April 1896. While the bells of the G.P.O. rang out the notes of God Bless the Prince of Wales and Home Sweet Home he wished that ‘God would bless the poor struggling artist and give him a home – be it ever so humble – and a little prosperity. The Prince of Wales can take care of himself.

Ultimately good fortune smiled on him, at the time of tragedy, when he witnessed and sketched the biggest fire Melbourne had ever seen, at Craig Williamson’s. It was a scoop. He sold his sketches to the Weekly Times, had a splurge with the proceeds at Baroni Studios, and never looked back. Commissions poured in. Tragedy, however, was to strike a few years later; his beloved brother Bert suicided, after months of illness and worry, on the sands of Sandringham.

Charlie was present to sketch the first shot fired in World War One when the German steamer Pfalz attempted to escape through Port Phillip heads. On account of ill-health, he retired to Belgrave where, in time, he built a fine house and ultimately, at the age of forty six, observed his Venus in the shape of Gussie Cecil, sister of the local schoolteacher. The final sketches show their meeting, courtship and marriage, leaving us with the comfortable presumption that they lived happily ever after.

One wonders whether Christopher Fry might have been thinking of Uncle Charlie when his ageing Duke began to court Perpetua:

Daylight is short, and becoming always shorter

But there's the space for an arrow or two between

Now and sunset.

Comments powered by CComment