- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Pragmatic and Idealistic

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Not the least of the many virtues of Michael Wilding’s Political Fictions is that it sets out its argument in a cogent way, stating its intellectual premises forthrightly and following them through with as little compromise as possible. This sort of ideological criticism (ideological, even though Wilding insists his judgments are primarily literary ones, and analyses the prose of the chosen novels closely) is rare in Australia. Here critics have mostly been content to proceed from a purely pragmatic basis – or, as the sympathetic would have it, have been content to be intelligent rather than ideological.

- Book 1 Title: Political Fictions

- Book 1 Biblio: Routledge & Kegan Paul, $34.50 hb, 226 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

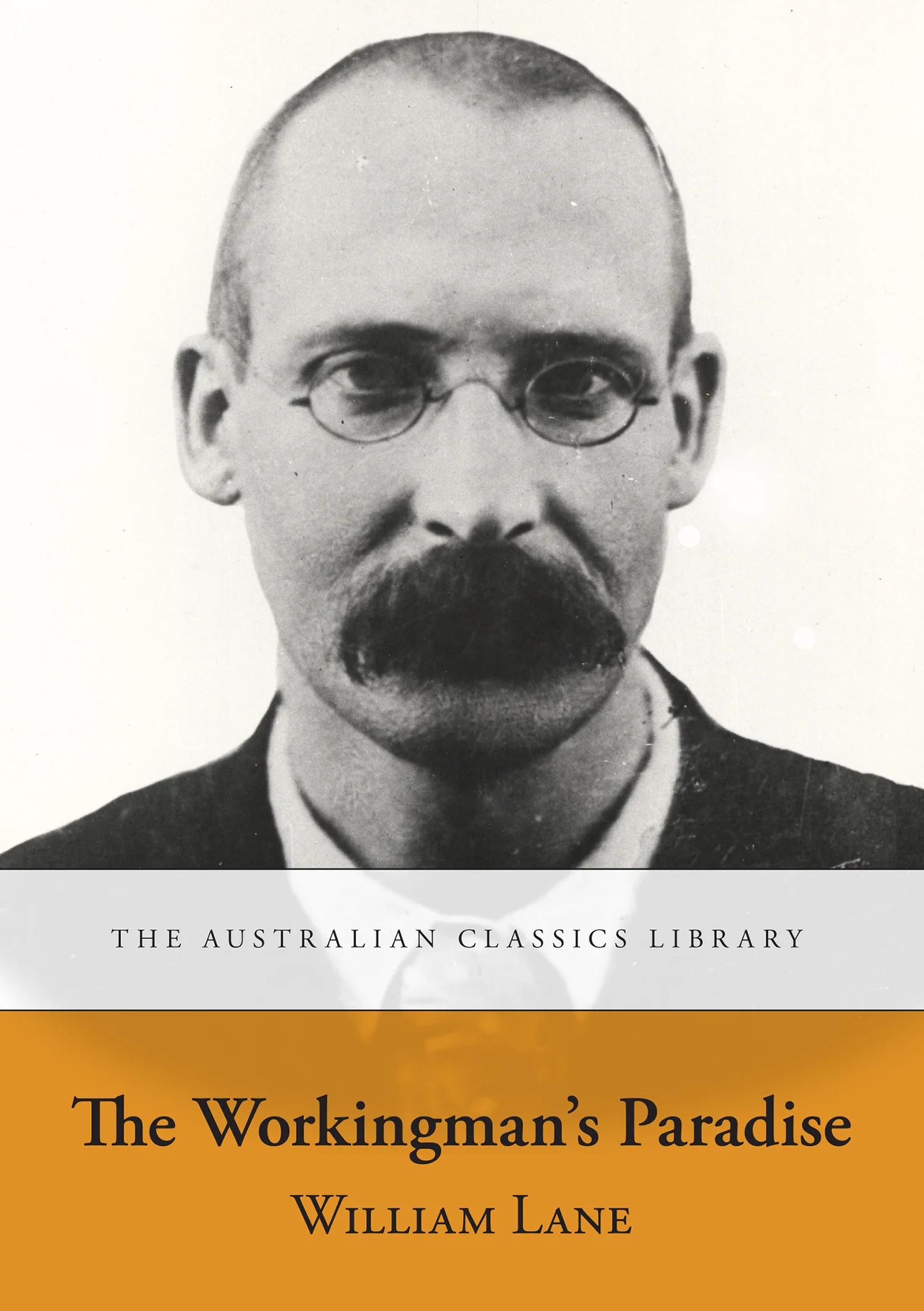

- Book 2 Title: The Workingman’s Paradise

- Book 2 Biblio: Sydney University Press, $10.00 pb, 225 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Wilding argues that ‘Fiction dealing with politics successfully is responsive to the forces of society; these forces manifest themselves in the cultural area, have their aesthetic expression. In political fictions we would expect to find not only the political conflicts of social choices, but also the aesthetic conflicts of fictional choices’. Lambasting the fictional tradition of ‘realism’, under which umbrella he crowds almost every major pre-twentieth century novelist from Fielding to Dickens to Dostoyevsky, he offers instead ‘alternatives to realism – through vernacular picaresque, dream vision, imaginary book, found manuscript, collage, utopian projection, dystopian fable, neo-neoclassicism, and through various mixed modes'. The books he chooses to write about are Huckleberry Finn, William Morris’s News from Nowhere, Jack London’s The Iron Heel, The Rainbow, Kangaroo, Darkness at Noon and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Wilding has something of interest to say on all these books. The most valuable chapters are those on Twain and Orwell. He rightly repoliticises Huck Finn, though without really acknowledging how much of an exception it is in Twain’s work, how consistently he denied the rebel in himself and submitted his darkest insights to the cossetting inspection of his wife. He notes more thoroughly than anyone else how heavily Orwell relied on Zamyatin’s We in writing Nineteen Eighty-Four, and how this helps to account for the sense of the novel’s staleness. The chapter on The Iron Heel sent me back to reading the novel but left my opinions unchanged. Itis simply impossible to get past the long chunks of exposition, the wooden dialogue, the stereotyped characters, the long stretches of mundane reportage and the narrowly mechanistic scientism. Wilding is correct in noting its imaginative and radical device of presenting' the novel as a manuscript, rediscovered and presented as a curiosity of seven centuries ago. But the clever idea of offering footnotes which purport to ‘explain’ the phenomena of our world quickly becomes glib, another excuse for the author to propound his opinions in the guise of certainties, with no opportunity for disagreement; for instance, a footnote explaining boxing says, ‘In that day it was the custom of men to compete for purses of money. They fought with their hands. When one was beaten into insensibility or killed, the survivor took the money’.

Wilding embarks on the formidable task of presenting Lawrence as a radical. He points to Lawrence’s stress ‘on the primacy of the individual’ but might have gone on to point out how few individuals this applies to in his fiction. By the time of Women in Love the characters seen as having any potentiality for individualism have narrowed to a tiny handful who dominate the foreground of the novel; in the background are the vast majority of others, not merely the miners but London intellectuals, for whom the author shows primarily contempt.

Wilding’s book is stimulating and provocative but to me at any rate unconvincing, not only in its argument but in the attempt to offer a radically different estimate of mediocre novels. The pressures on writers to write politically and on critics to read them politically in this generation are immense. But the value of a novel does not lie in the extent of its capacity to move us to political action, or in its espousal of radical change. Otherwise, when the occasion for action disappeared so the worth of the book would decline. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was never, not even in the mid nineteenth century, a masterpiece. A great novel may well be a successful act of propaganda but this is not the source of its greatness.

In fact, I suspect that, like it or not, most great art is profoundly conservative in nature, even in this century when this has begun to change. Perhaps a novelist intent on making order out of the chaos of experience necessarily values that order excessively. Perhaps too, at least until this century, even agnostic novelists would subscribe to Patrick White’s announced ambition to give unbelievers at least a glimpse of what they do not believe in, and this search for hidden spiritual meanings beneath the surfaces of life perhaps leads, even if not with intent, to some form of reconciliation with life on what Vladimir Nabokov calls ‘this pellet of muck’. There is hardly a wholly secular novelist in English bctween Henry Fielding and the Joyce of Ulysses. Even now it is rare to find a writer like Brecht who is simply impatient to sweep the distracting and irrelevant God business out of the way so that he can set about tackling what he sees as the real business of living.

But there is no reason to denigrate the tradition of the nineteenth century novel – of Dickens, Hardy and Eliot among others – on that account. Though he throws the terms ‘bourgeois’ and ‘realism’ around freely as pejorative tags even Wilding draws the line at attacking the great and profoundly pessimistic masterpiece of nineteenth century English realism. Middlemarch. The furthest he goes is to refer to its function of ‘the necessary belief in bourgeois individualism’ in assuring ‘those whose faith has evaporated’ that ‘the design of bourgeois life is innately aesthetically pleasing’. This hardly corresponds at all to what I would value as the novel’s extraordinary sanity and even wisdom, the complexity of its insights into the nature of class relationships and structures, and the deeply disturbing nature of its pessimism in regard to human aspiration.

The reissue of The Workingman’s Paradise, written by the noted radical William Lane under the pseudonym of John Miller in 1892 during the period of the founding of Australian unions and the Queensland shearers’ strike, is a logical continuation of Wilding’s work. This latest volume in the series Australian Literary Reprints is accompanied by a long, scholarly introduction (160 footnotes!) by Wilding which I found more absorbing than the novel itself.

As a piece of fiction, its value is pretty minimal. It consists almost entirely of expositor) conversation between Ned Hawkins and the young woman with whom he falls in love. Nellie Lawton, the novel’s most important and interesting character. Lane directs our attention un- flaggingly to the appalling social conditions of Sydney during the eighteen nineties – women being forced into prostitution or almost starving to death as seamstresses, men sleeping out in the open until they are jailed or booted on by the police, the active collusion between business and police in order to ensure the failure of the unions.

One of the most striking things about it was the similarity to The Iron Heel. In both novels a rather pallid and conventional love al fair occupies the foreground; in The Iron Heel it is between a revolutionary with the remarkably phallic name of Ernest Everhart! and a young woman of the upper classes who narrates the story. In both, there is one member of the ruling classes who stands out from the generally contemptuous presentation of them in both novels because he unacknowledges unapologetically that he is representative, not of right but of naked power for its own sake. Though marked by racism. however, Lane’s novel is superior in its less sentimental attitude towards its heroine and in its insistence on rejecting hatred as a motive for radical action.

Comments powered by CComment