- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Poise and Evocation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Gary Catalano’s book, which I admire greatly, is a readjustment. His standpoint, so far as I can tell, is an ideal he has of what might be the suitable creative situation for artists, and he reviews the 1960s with this in mind.

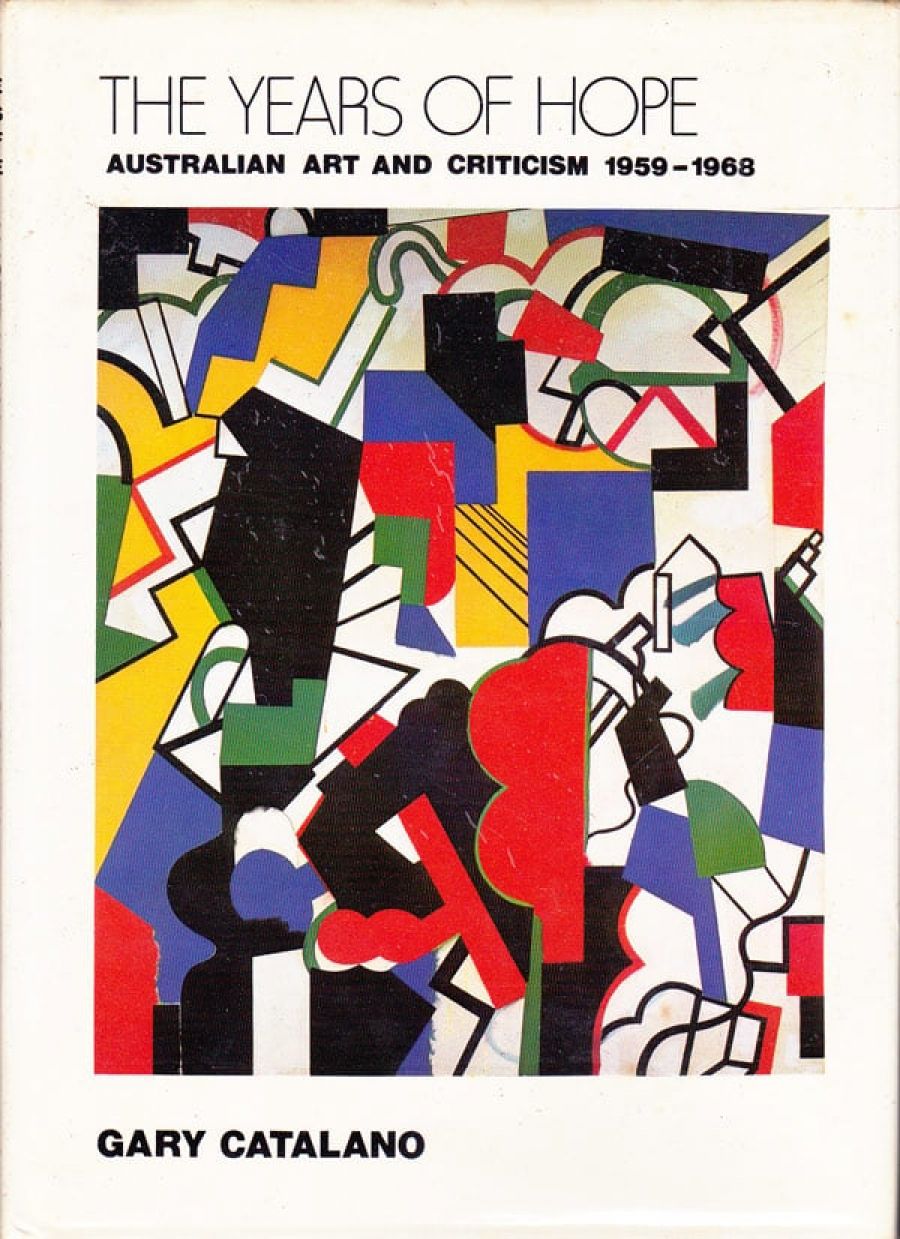

- Book 1 Title: The Years of Hope

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian Art and Criticism 1959–1968

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, $19.95, 215 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Catalano’s ideal artist has the capacity and confidence to work from himself, his locality and milieu. The author is at his best when demonstrating this capacity in the ‘imitation realists’, Robert Rooney, Dale Hickey, Jon Molvig, David Strachan, and others. The book starts as if its theme is nationalism:

The Antipodean exhibition [1959]. whatever its immediate purpose, formed a high watermark in Australia’s sense of confidence in the potential of its society, yet beyond that trail of salt and broken shells The Field [1968] was an emphatic rejection, if not of such confidence, then at least the idea that art should be its vehicle and its voice.

But if nationalism is the theme, it is underground most of the time, and in any case is important to Catalano only in so far as it promotes artistic independence.

We could try another tack, and say that the writer corrects the past from the viewpoint of the late 1970s. A decade ago, it could appear that Australians had at last left the backwater and plunged into the international mainstream. Too late as usual! By 1970, the mainstream was dissipating fast; what had seemed to be an evolutionary principle of creativity then emerged as a vulnerable concept. Even before 1970, Robin Wallace-Crabbe had observed that hard-edge was ‘not, of course, international’, but an ‘involvement spread from. a few centres to countries generally under their influence, politically, economically’.

But trying to squeeze a central argument from Catalano’s book is inappropriate to his themes and lateral style of construction.

Poise is the book’s dominant characteristic. One is struck by the cool way it unsettles authoritative opinion. In a continuous shadow-boxing with other writers Catalano manages to show that certain developments in 1960s art were mistakenly perceived by older contemporaries – even demonstrating that what commentators said was happening was in fact the reverse.

The critics, he argues, didn’t know much at all about the overseas movements that were, or conversely were not, exciting young artists in Sydney and Melbourne. Tachism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop – some critics who used the labels didn’t know what they really entailed. (The writer occasionally slips up, as when he misreads James Gleeson and misinterprets John Brack.)

In particular, he writes around Bernard Smith, whose Australian Painting is a silent voice in the background of most of the book. At times the dialogue with Smith is open (the Antipodeans – and look at the index!) but often, unfortunately, it is implicit.

The difference between them is instructive. Smith’s outline is clear. He calls the 1940s ‘Rebirth’. The 1950s he represents by the tension between ‘Figurative and Non-Figurative art, continuing this into the 1960s, to which he devotes no less than four chapters. He distinguishes a shift ‘Towards a Metropolitan Situation’, and elucidates three main stylistic tendencies, ‘Expressive and Symbolic’, ‘Pop art and traditional genres’ and from 1965 "Colour Painting’. All very straightforward and carefully proportioned.

By contrast Catalano is provocative – the most significant event in Australian art during the 1950s was the ‘discovery’ of primitive art, particularly that of the Australian Aboriginals’ (chapter on ‘The Primitive Impulse’); he is whimsical – ‘Perhaps we can see the child painting of the Antipodeans … as an expression of Australia’s ability to make a fresh start as a society, free from both the complex responsibilities and the vain sophistication of Europe’ (chapter on ‘Childhood Themes’); and indirect – as is suggested by the chapter titles "Other Styles, Other Images’, The Absence of Pop’, ‘A Dog’s Breakfast’, ‘The Second-Class Citizens’.

His exposition is allusive. I still don’t know whether the supposed ‘absence of Pop’ is an illusion. Were Mike Brown, Ross Crothall, Ken Reinhard, Robert Rooney, Dick Watkins, and Michael Allen Shaw exponents of a local type of commentary we could label Pop for want of a better word? I am not remotely interested in the problem and perhaps neither is Catalano, but it ‘Pops’ up in different guises throughout the book, and indicates something at the heart of Catalano’s aesthetic that he never quite comes forward with: the critical point at which an artist’s interested observation of other art shades. off into creative dependence. The book’s nationalism, its observations of local traditions in Sydney and Melbourne, its quibbling over terms, and discussion of what the critics said, are explained by the test of cultural independence.

Otherwise, Catalano’s lengthy argument with critics over their use of Tachism, Abstract Expressionism, etc. is a red herring: there can be no exclusive definitions of these art movements. What contemporaries thought they meant is far more valuable for understanding local culture than the supposedly correct version – which Catalano brandishes, but withholds from us anyway!

Catalano is a poet, an aesthete, whose concrete observations play havoc with well-connected argument. Everything is murky when one looks for clear exposition but perfectly lucid if one considers the integration of many separate perceptions. Ultimately, the reader is transposed, inheriting quite another feeling for the 1960s, and the process by which this happens is all the more thorough for being by indirection. Catalano addresses us not with a voice only, but primarily through impressions.

His sensibility is his best argument, and he makes brilliantly evocative use of it. One will go back to the book often for passages such as these:

Kemp’s (work) is by no means simply concerned with formal problems, for much of his work is animated by an almost mystic faith in science – something he shared with the Sydney abstractionist, Ralph Balson. And like Balson, Kemp dramatises not the spirit of scientific enquiry but the shifting, relative and even fearful world it issues in.The run of spots which Olsen superimposed on his painted lines became, in the hands of the imitation realists, real beads running along the contours of form; his leering faces were transferred to the tops of tin cans and nailed to the picture surface. It only went to show that they shared in his appreciation of Australian vulgarity!One is often struck by the remarkable similarity between the declared intentions of the Antipodeans and those of Sydney’s abstractionists. When, for instance, John Perceval talked of attempting to paint ‘the vitality, the pulse of life in nature and the world around us’, he was also speaking on John Olsen’s behalf: when Tom Gleghorn mentioned his desire ‘to express things in paint that can’t be put into words’, he was echoing oft expressed sentiments of Blackman’s.

Comments powered by CComment