- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Journalism

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Patriot and a Blunder

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The blurb is right enough: Sir Keith Murdoch probably was Australia’s greatest newspaperman. Quite unusually for a press tycoon, he had been a very good journalist and a brilliant editor. In his time the Melbourne evening Herald and Sun News-Pictorial were, technically, remarkable innovatory newspapers.

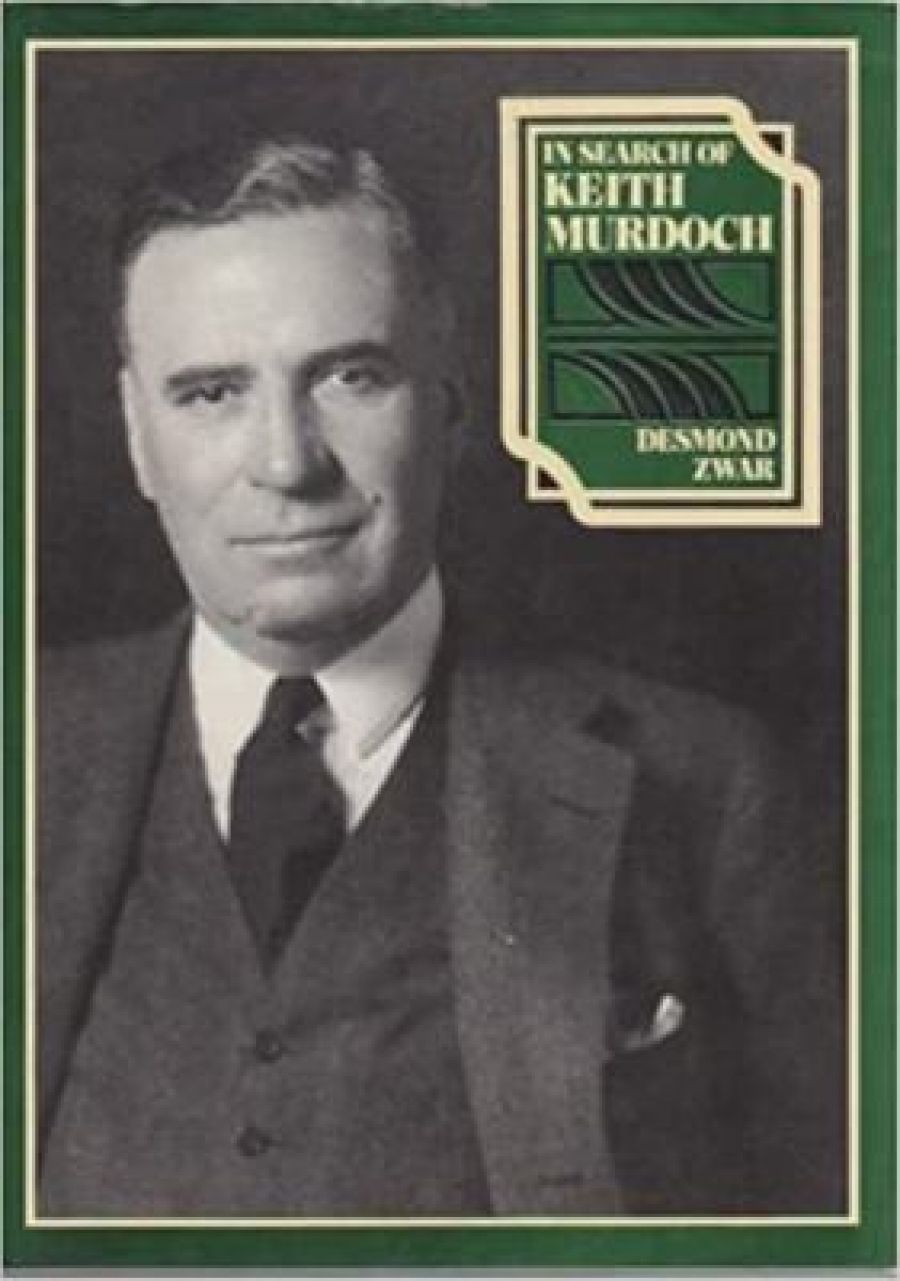

- Book 1 Title: In Search of Keith Murdoch

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $17.95, 130 pp

Desmond Zwar’s semi-official biography is a ‘quickie’ based on the unpublished commissioned work by the late C. E. Sayers. It is much better than nothing – it blocks in the life usefully, quotes revealing letters at length, and has some good photographs. But it is shallow, and not good questioning journalism, let alone a sensitive biography which grapples in depth with characters and motives. Zwar is not uncritical but interviews with the Murdoch family contribute to an overall impression of pious reverence.

About one third of the book is on Murdoch’s years overseas as a young man. After experience on the Age and an unsuccessful attempt to break into Fleet Street, by his mid-twenties he was reporting Federal Parliament for the Sydney Sun and was on close terms with the leaders of the Labor government. On the outbreak of the 1914–18 war C.E.W. Bean just defeated him in an election by journalists for the appointment of official War Correspondent. In 1915 Murdoch was appointed to manage the United Cable Service in The Times office in London. On the way, he visited Gallipoli briefly and in a letter to Prime Minister Andrew Fisher denounced the conduct of the campaign. It was shown to Lloyd George and other members of the anti-Gallipoli faction in the British government and had much to do with the recall of General Hamilton. Zwar usefully prints much of the letter (mistakenly asserting that it has not been published). But he does not fully face the real charge against Murdoch, which was not simply that he had broken his pledge to observe the censorship regulations, but rather that the letter teemed with exaggeration and error. It seemed to the senior A.I.F. men that he was either very gullible or a ruthless liar (or perhaps both).

Based in London for the rest of the war, Murdoch was Prime Minister Hughes’s ‘fixer’, reporting on political developments and organising the conscription campaign among the troops. With remarkable aplomb for a man of thirty, he entertained cabinet ministers and senior generals at dinner or confronted them on Hughes’s behalf, including the Commander-in-Chief Haig. Accredited as a war correspondent, he wrote some vivid despatches from France which, in general, were superior to Bean’s. And always he was plotting for what he brashly considered desirable Australian objectives. Zwar misses the most remarkable plot of all – the attempt by Murdoch and Bean in 1918 to have Monash replaced as corps commander by Brudenell White, which takes some beating as the most irresponsible act by pressmen in Australian history.

One of the book’s virtues is that it provides a handy outline of the growth of the Murdoch empire. While he was still in London, enjoying an extraordinary filial relationship with Lord Northcliffe, Murdoch was picked out in 1921 by Theodore Fink, chairman of directors of the Herald & Weekly Times Ltd, to take over the stodgy Melbourne Herald. In 1922 Murdoch faced an invasion from Sydney by Sir Hugh Denison who launched the Sun News-Pictorial and the Evening Sun. Murdoch had a complete victory: within two years the Herald bought Denison out cheaply. By the late 1920s Murdoch was managing director. He had already begun his takeovers as head of a syndicate based on the Herald board: in 1926 of the West Australian, then of the Adelaide morning papers the Advertiser and Register (and later the evening News for good measure), then in 1933 the two Brisbane morning dailies. Nothing like this concentration of newspaper power had ever been known in Australia. In the mid-1930s, after his first major heart-attack, Murdoch narrowly withstood an attempt by Fink to get rid of him. He retained power until his death in 1952 although, remarkably, in his last days he was planning to leave the Herald for the Argus.

Murdoch needs a thorough, unreserved, extended biography; without it, his real stature and place in history cannot be properly assessed. He was a great trainer of journalists, who usually respected him. He made a major contribution to the arts, especially as chairman of trustees of the National Gallery of Victoria, and in the space he gave in his papers to advanced critics. The origins of his ambition, which aimed at power and fame more than wealth and status, were probably largely in his unfortunate stammer which made much of his childhood miserable. How he used that power needs close investigation. Essentially his political views were unsophisticated and conventionally conservative. He was both a great patriot and often a stupid blunderer. As is the case with most press tycoons, his quite astounding trait was his conviction that he knew so much better than the rest of us.

Comments powered by CComment