- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Old New Wave

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The end of the decade seems an appropriate time for a re-assessment of the revival of Australian cinema, since the beginning of the seventies can be taken as the time when it struggled towards life. Somewhere between the two Burstall films, Two Thousand Weeks (1968) and Alvin Purple (1973), there took place the various stirrings of conscience, consciousness, initiative, and enterprise that led to something over one hundred and fifty films in the next ten years. David Stratton’s book lists one-hundred-and-twenty-eight films, although different listings have discovered more, and he is also at pains to pay appropriate tribute to the pioneering efforts of Burstall.

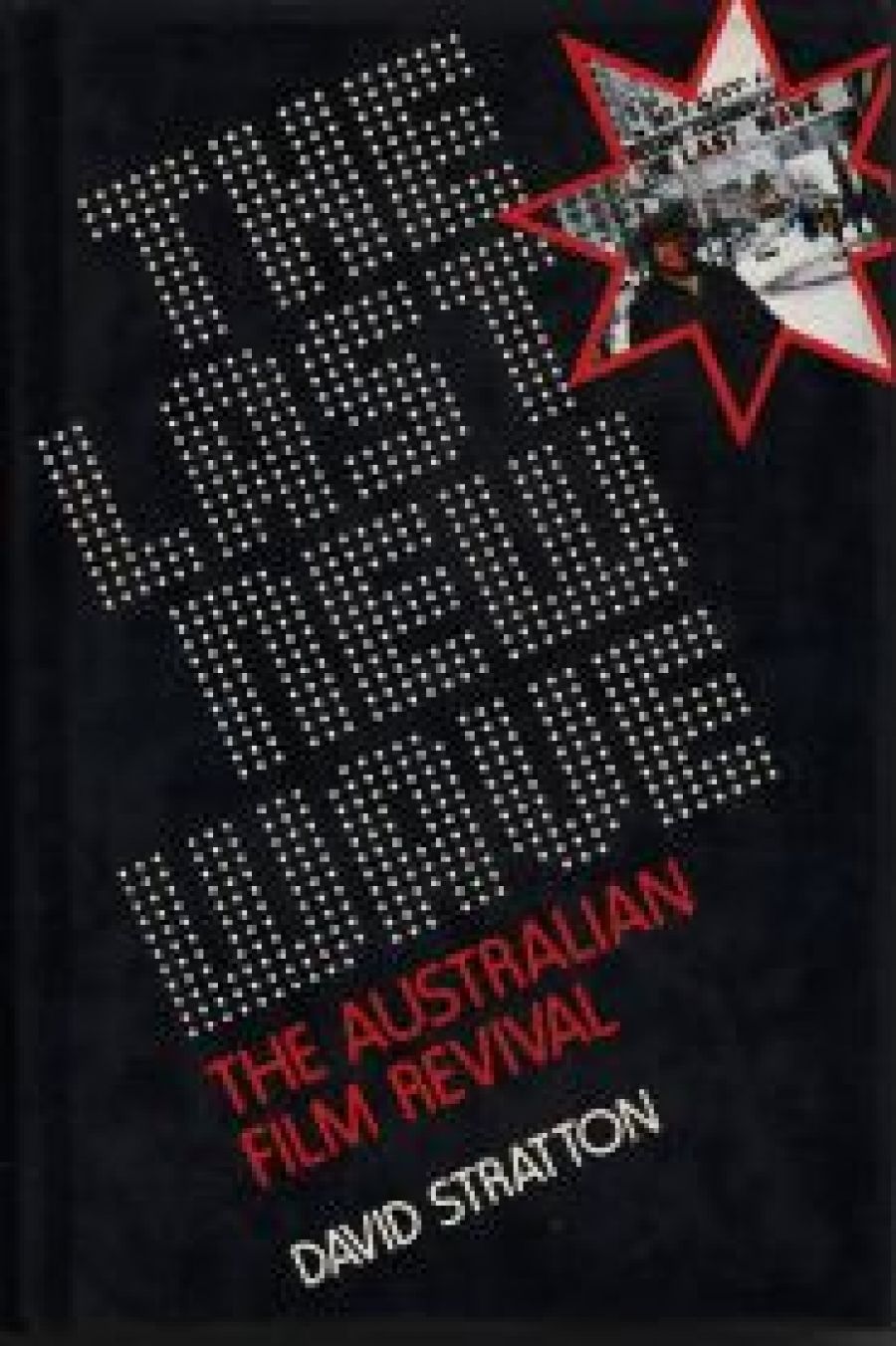

- Book 1 Title: The Last New Wave: The Australian film revival

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus & Robertson, $19.95, 337 pp

Beyond that, he is more concerned, as he says, ‘to explain how and why the films were made than to discuss the films themselves in aesthetic terms’ and he does this largely by relying on the comments of film-makers themselves. Thus the book at first looks like an auteurist study, with chapters on the major directors. Ten directors have chapters to themselves, another ten have parts of chapters and there is a chapter on producers, though nothing, except incidentally, on writers. As an organising principle the auteurist approach is understandable; in the assumptions it contains it is worrying, especially since much of what Stratton has to reveal about the circumstances of particular films reveals just that mixture of chance, randomness, co-operation (and its opposite) and corporateness, which are the kinds of things which have brought auteurism under question as a critical method.

There are other problems with the method Stratton has chosen. It was of course impossible, and he must surely have known it would be impossible, to simply give an account without making aesthetic judgements, and in fact Stratton’s comments are liberally sprinkled with terms which present his own opinions. Terms like ‘beautifully made’, ‘sleazy’, dismal in the extreme, ‘witless’ occur in the first chapter, and The Nickel Queen, for example, is ‘... technically … poor, with harsh lighting, slack editing and pedestrian direction to complement the charmless actors’ while The FJ. Holden is ‘… one of the most vital, energetic, honest and uncompromising of Australian films’. Stratton can even assert critical opinion as though it is historically uncontestable. In fact, he says of My Brilliant Career ‘the scenes between Sybylla and Harry which Ms. Hall found dull and disastrous are beautifully handled’.

Stratton’s admirable enthusiasm, and his freely expressed critical judgements (many of them attempting to rescue worthy films undeservedly neglected by the public and mistreated by critics), may get him into difficulties in terms of his original self-imposed brief, but it allows him to follow one theme consistently in his account of the decade, namely the vexed issue of the role of reviewers. He is properly harsh in his treatment of some of the reviewing tribe. P. P. McGuinness, for years believed by the National Times to be a film critic, quite deservedly gets the harshest treatment, while Geraldine Pascall is quoted extensively to appropriately damning effect. Stratton worries about the role and the effect of the newspaper critic and his work. He points to favourable overseas reviews of Australian films and asks, in anguish, ‘What satisfaction do our reviewers get from destroying a filmmaker and his work, while paying lip service to the notion that an Australian film industry needs support?”

It is a fair question, given that some of the overseas reviews quoted (The Picture Show Man, for example) point to qualities such as mood or humour which local reviewers do not appear to respond to. And it is no help for practioners like Michael Pate to say, ‘Critics seem to me to be just envious; why don’t they go out and make the films themselves? (especially after a remark like, ‘They wrote absolute total crap – not even good English’). What is needed is not critics making films, but critics, competent, qualified and sympathetic, who will write good criticism.

Stratton himself provides an example here, for his own critical judgements vary. Where, as with The FJ. Holden, his comments are detailed and specific, referring with understanding to the elements of the film, they are enlightening. But despite his original disclaimer, he tosses off other judgements supported by nothing more substantial than his own subjectivity. Thus actor Max Gillies is treated with consistent harshness ‘… one of the worst performances seen in an Australian film since the thirties … ‘of Gillies in Dimboola, and ‘… the character of Dr. Woolf, abominably played by Max Gillies … ‘of Pure S. Even praise is damningly faint: ‘… it’s true that the role suited Gillies’ eye-rolling, “play to the gallery’” style, and that in consequence it is his best screen performance’ of The True Story of Eskimo Nell. Has not subjective dislike of what is perceived as one kind of acting style led here to a destructive treatment of a fine actor?

The more central theme of the book, nevertheless, is the how and why of production, and much of what emerges here turns out to be one of the best things done on the gap between what we see on the screen and the excitements, agonies and frustrations of production and, even more, post-production. It may -be that not all of these concerned will agree with the accounts presented of, for instance, Sunday Too Far Away, Newsfront, My

Brilliant Career and Blue Fin, but the ‘interview with filmmakers’ technique, for all its inadequacies, provides valuable potted case studies of production problems.

One wonders, too, how far the memories of film makers are reliable when they are talking about their own achievements. And given the place this work will occupy in the developing history of Australian cinema, it would be reassuring to know that it is fact rather than interpretation and opinion we are getting.

Still for anyone interested in Australian film, the Australian culture, this is a compulsively readable book. The author’s enthusiasm for his subject informs every chapter and it also, on one crucial question, puts him on the side of the angels. He is strongly for the authentically and honestly Australian work, and properly scornful of ‘bland

internationalism as a cheap film-making formula’. It is a crucial question because, in the continuing crises Australian cinema will inevitably face, it will be on the resolution of that question that the future of any Australian film production worth the name will depend.

Comments powered by CComment