With the reissue of The Beauties and Furies (1936) this month by the British feminist press Virago, virtually all of Christina Stead’s work is in print for the first time in the half century long career of this distinguished writer. That this is so is largely due to Virago Press itself, which has reprinted no fewer than eight of Stead’s books, five of them in their Modern Classics series. Apart from the early novel, the others are For Love Alone (1945), Letty Fox: Her Luck (1946), A Little Tea, A Little Chat (1948), The People with the Dogs (1952), Miss Herbert (1976, also known as The Suburban Wife), Cotters’ England (1966, also known as Dark Places of the Heart in the United States), and a selection from almost all her work, A Christina Stead Reader. Next year they plan to publish her collection of novellas, The Puzzleheaded Girl.

While not all of these novels live up to the highest quality of her best work, they help to set it in context and make clear what a substantial and formidable body of work hers is.

The Beauties and Furies, her third published book and probably the least known of any of Christina Stead’s novels, has been out of print virtually since its first publication until now. The few critical references to it tend to be casually dismissive and treat it as the conspicuous failure among her first five books. There is some truth to this. It is certainly a garrulous and overwritten novel, its characters possessed of that almost preternatural articulateness and volubility that distinguish so many of their creator’s protagonists. The novel also embodies much of the characteristic tension in the early work of Stead between extravagant flights of romantic fancy on the one hand and gritty, documentary-like observation of sordid demi-mondes on the other. But in its preoccupation with the workings of the female psyche and in its shrewd, hard-headed by largely dispassionate observation of the cafe world of Paris in which most of the characters circle aimlessly, it shares many of the same concerns as the other novels of its author.

At the opening of the novel, its thirty-year-old heroine is fleeing her doctor husband to join a young student in Paris who has declared himself passionately in love with her. Elvira is one of the first in a long line of Stead women: physically attractive, emotionally immature and vulnerable, susceptible to flattery, she has much in common with such women as Miss Herbert or even the apparently tough-minded Letty Fox, though she lacks the real inner strength of Teresa Hawkins in For Love Alone. On the surface romantically inclined, she is at heart the essentially conformist, bourgeois-minded woman that Letty and Miss Herbert are. She has her affair in Paris, dithers delightedly between faithful husband and romantic, Adonis-lover, becomes pregnant and hesitates again before deciding not to have the child. Finally, predictably, she returns to the financial and emotional security of England.

Elvira is a challenging character, especially in the early stages of the novel. There is at times a certain salty shrewdness about her observation of men. Of her husband Paul, for instance, she notes, ‘A bachelor weekend. These men love to get each other off into stag huddles in the weekends: they get crushes on each other – his patients are in the City, and the City is a sort of stag-party.’ In response to Oliver’s sentimental idyll of ‘a woman’s hand wandering over the ivories ... a woman, a soft, reluctant voice, music, flowers’, similarly, she says with some asperity, ‘A woman is a human being, not an aesthetic gratification.’ She tries honestly to confront the issues of female freedom and equality. ‘The real thought of the middle-class woman,’ she complains, ‘is the problem of economic freedom and sexual freedom: they can’t be attained at the same time. We are not free. The slave of the kitchen and bedroom.’ It is a familiar plaint among Stead heroines but one to which there is no easy answer. In the course of the discussion with Oliver of which this is an extract, Elvira draws an analogy, also frequently to be met with in the novels, between the roles of housewife and prostitute. As the novel proceeds, however, she becomes steadily tamer. As her husband says of her, ‘Her self-respect is everything to her, and she likes to be on the right side of the law and of the proprieties.’

Early in the novel, the lace manufacturer Georges Fuseaux makes a speech in which he declares that ‘the only fine designs the Rothschilds are interested in are the arabesques on banknotes’. In Christina Stead’s fiction, there is always a tension between what this dichotomy suggests – the fantastic and extravagant versus the utilitarian and materialistic - but it is usually banknotes, especially in the later novels, that win out. In this novel the elements of the extravagant and exotic are certainly there. The presence of that Jacobean figure Marpurgo, forever hanging on the edge of the action and attempting to influence it with his mad speeches and devious plotting, is one example of this. Coromandel is an equally exaggerated figure, though good rather than evil. Elvira’s wild dream is followed by the superbly sensual scene in which this ‘strange sensuous water-animal’ as she is described lovingly inspects her own naked body while, unknown to her, Oliver is watching. Even ‘The Story of the Hamadryad’ reads like a leftover from The Salzburg Tales. One of the most puzzling elements in the novel – and the one that most completely exemplifies the ‘arabesque’ side of Stead’s talents – is the visit of Marpurgo and Oliver to the Somnambulists’ Club. In this scene, perhaps influenced by Ulysses to which there are several references in the novel, Marpurgo plays a sort of malign Bloom to Oliver’s Stephen. It is one of the strangest and most fantastic in the novel and it culminates in Marpurgo’s giving voice to his demonic philosophy: ‘the world is insubstantial and inane, a big-swollen nihility, air compressed by the devil into a borrowed and delusive form’.

But there are elements in the novel which are very substantial indeed. In the background to the swirling, tumultuous intrigues and amorous deceits of the main characters are the implacable mercantile realities of Parisian life. As she was to do later of banking in House of All Nations, Christina Stead reveals a formidably detailed and exhaustive knowledge of the Fuseaux brothers’ lacemaking business, from the actual process of manufacture to the economic basis and organisation of the firm.

Money is never far from any of the characters’ lives and consideration. Elvira returns to her husband not least because of the security he can provide. Oliver is allegedly a radical and admirer of revolutions but his studies in Paris are financed by his uncle and he cuts his scholarly cloth cautiously so as not to jeopardise his future chances of academic employment. He is quick to grab at any opportunity of employment in the business world. Marpurgo spends lavishly on his expense account but his position with the Furnaux bothers is increasingly uncertain and he becomes panic-stricken when he is eventually fired. But the clearest example of total subordination of one’s interests and mode of life to economic considerations is that of the actress Blanche d’Anizy, a not entirely unsympathetic character who lives virtually as a prostitute in order to support herself and her child. For all its flights of fancy. the strongest impression The Beauties and Furies leaves us with is the disreputable, avaricious nature of the Parisian urban world in which the characters’ dreams and fantasies are pursued.

I will pass over For Love Alone as having already been discussed in some detail by others as well as myself to move immediately to the so-called New York trilogy that Christina Stead wrote while resident in the United States. Letty Fox: Her Luck and A Little Tea, A Little Chat are in some ways companion pieces. Both have at their centre a character who is almost compulsively promiscuous but although overt judgments of characters are as rare in these novels as in any of Stead’s the presentation of their behaviour in the two novels is quite different.

Letty Fox is sometimes sentimentalised by feminist critics. Meaghan Morris, for instance, in her intelligent introduction to the Angus & Robertson edition of the novel, claims that ‘Free love is free only for men, who have the power to withhold emotional commitment which Letty can never do once an affair is underway.’ This is what Letty herself argues; I don’t think it’s how Stead would have it. Apart from the fact that it ignores both Letty’s unscrupulousness in her pursuit of what she wants (she tricks a woman out of her apartment, pursues unscrupulously even men who are already committed, attempts to blackmail a lover into marriage, deceives her husband-to-be with two men before he has even time to consummate her marriage, and betrays her sister twice) and her remarkable resilience in bouncing back from these affairs in which she was unable to withhold her love, the novel certainly does not argue that emotional commitment is the exclusive prerogative of one sex.

What is truly impressive about Letty, though, is her emotional honesty, her refusal to put a hypocritical gloss on even the least attractive aspects of her conduct. If this is a limited, perhaps even negative virtue it is nevertheless a real one. ‘Men,’ says Letty, ‘don’t like to think that we are just as they are. But we are much as they are; and therefore, I have omitted the more wretched details of that close connection, that profound, wordless, struggle that must go on in the relation between the sexes.’ Her claim is justified, and the great quality of the novel, one that places it years ahead of its time, is the immediacy, the fullness and the authenticity with which it chronicles the realities of a woman’s attempt to overcome sexual and economic harassment and inequality. It is a conclusive indictment of the double standard in sexual morality. The novel neither idealises nor pours contempt on Letty. It merely records with unjudging sympathy the extremes of behaviour to which social imperatives force her: in a witty parody of the Jesuit boast Mr McLaren observes, ‘let me have a child during the first seven dollars and I can guarantee its success afterwards’.

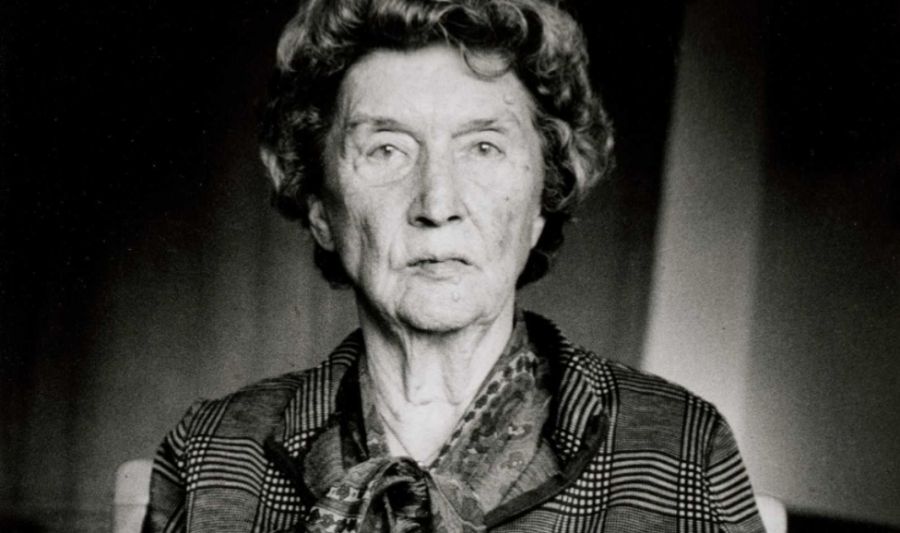

Christina Stead (photograph via Text Publishing/National Library of Australia)

Although some of her qualities spring uniquely out of the world of Stead’s novels – her extraordinary articulacy and garrulousness, for example, as well as her pretensions to writing – she is, justifiably seen as being to some extent a representative woman of her time. (In particular, she is a representative New Yorker: after asking herself why all her lovers abandon her, she gives the uniquely New Yorker answer – ‘because I had no apartment to which to take them’. Though she competes frantically against other women for any suitable men she associates herself also with ‘the tribe of women’. Like Elvira she points to the analogy between marriage and prostitution and twice turns angrily on the stuffiest of her lovers, denouncing prostitution as a social habit instituted by males. She tells Cornelis, ‘you don’t know the first thing about women, which is, that when you live with them, they begin to love you. This is because they are more earthy and also more honest than you are. When they give their body, they give their heart and soul, too. Isn’t that honest? It is men who whore!’

The portrait of Letty Fox, while less than flattering, is basically sympathetic. That of Robbie Grant in A Little Tea, A Little Chat on the other hand, is an appalling and appalled one, even though superficially his behaviour might seem to be similar to hers. Grant is, without doubt, the most odious character in all of Stead’s fiction, the one indisputably wicked man in all her work. I suspect that critics who rail against Samuel Pollit have not read this novel because, when placed against Robbie, Sam comes to appear almost angelic.

The world of this novel is the same dense, crowded, bustling metropolitan New York of Letty Fox, another of Stead’s brilliant portraits of cities, but what is hard-headed realism in Letty herself (told of Uncle Philip’s suicide she comments tersely ‘He died for love. But I don’t want to’ becomes unscrupulous and pusillanimous cynicism in Grant; and what is resilient energy in her case is a kind of febrile yet self-protective pursuit of hedonism in his.

Grant is rare among Stead’s central characters in being rich and never in want of money, yet he is, if anything; even more materialistic and obsessed with questions of profit than any of his predecessors among her fiction. The world of the novel is very much the aimless, amoral world of Letty Fox and Grant moves through it, spending the bulk of his time with women, sleeping with most of them but gaining little satisfaction from it. Stead, who is far more disposed to comment directly on him than she usually is, observes that ‘He had little pleasure out of his own real hobby, libertinage, and he gave none. Women fell away from him, but he did not know why; and he retained only the venal.’ He has a corny line as a seducer: ‘A woman like you could keep a man. I’m looking for an oasis in my desert, a rose on a blasted heath ... I’m looking for romance. My heart needs a home, a cradle, eh? I’ve used myself up, played too hard. Now I need a woman, a mother, a sister, a sweetheart, a friend.’ But the sheer indefatigable energy of his pursuit, backed up by the delusive promise of his riches, nets him a fair number of successes.

In the course of the novel, Grant not only seduces a large number of women (at one stage his son overhears him making telephone calls to seven women in succession, offering substantially the same patter) but drives one of them to suicide, engages in speculative profiteering despite his professed socialism, shows no love for his young son, steals a play which he had commissioned and refuses to pay for, sends anonymous letters to undermine two of the women with whom he had fallen out, refuses to pay his closest associate the money to which he is entitled, and drives several women to financial ruin by reneging on his promises of financial assistance.

Throughout all this, he is able to convince himself that none of it is his own responsibility. Robbie’s capacity for self-deception is on a par with that of Stead’s portraits of other great egotistical self-deceivers – Sam Pollit, Jonathan Crow, Henri Leon (in House of All Nations) and Nellie Cook in Cotters’ England. We see this trait especially in his repeated reconstructions of the suicide of Mrs Coppelius, for which he was responsible. The author tells us first that ‘Never once did he allow himself to think of the woman. It was a simple black-out in his mind’, but later, when he does begin to think about her, a remarkable process of sublimation takes place. In one version, Grant’s victim becomes a beautiful Italian woman Signora Maria Coppelius whom he meets only incidentally and who is driven to her death by a priest whose mistress she was! Numerous other versions that follow later are even more ingenious and further from the truth. Similarly, his method of coping with his own grievous faults and avoiding self-knowledge is to project them onto other people. Thus, a man whom he ruins by his false promises of financial collaboration becomes a case of ‘Megalo-mania’, and he advises his son to dismiss an employee on the grounds that he is a ‘libertine’!

Again, as with Letty Fox the background to this examination of sexual depravity is political and especially that of the war (both novels are set largely in wartime). At one point Stead tells us savagely, ‘Everyone scooped greedily in the great cream pot of war.’ Grant plays at being a ‘pinko’ partly because ‘leftist’ girls are assumed to be easier to get: despite her own professed socialism, Stead has presented us with a more scathing indictment of socialist and pseudo-socialist characters than most right-wing authors.

The depiction of both Grant and the New York he inhabits, then is a degrading one. In The People with the Dogs on the other hand, Stead seems to be attempting to redress the balance a little. This novel is in many ways the most attractive of the three New York ones, if only because its low-keyed mood and reflective, leisurely approach are something of a relief to come to after the hurtling pace of the previous two.

The novel opens. characteristically for Stead, with the sentence ‘In lower Manhattan, between 17th and 15th Streets, Second Avenue, running north and south, cuts through Stuyvesant Park; and at this point Second Avenue enters upon the old Lower East Side’. As so often, the author begins by locating us firmly in time or place or both: shortly afterwards we hear it is ‘just after the war’ as well.

Compare the openings of the following novels:

The express flew towards Paris over the flooded March swamps.

The Beauties and Furies

They were in the Hotel Lotti in the Rue de Castiglione, but not in Leon’s usual suite.

House of All Nations

All the June Saturday afternoon Sam Pollit’s children were on the lookout for him as thev skated round the dirt sidewalks and seamed old asphalt of R Street and Reservoir Road that bounded the deep-grassed acres of Tohoga House, their home.

The Man Who Loved Children

One hot night last spring, after waiting fruitlessly for a call from my then lover with whom I had quarrelled the same afternoon and finding one of my black moods on me, I flung out of my lonely room on the ninth floor (unlucky number) in a hotel in lower Fifth Avenue and rushed into the streets of the Village, feeling bad.

Letty Fox: Her Luck

Peter Hoag, a Wall Street man, aged fifty-six in March. 1941 led a simple Manhattan life and had regular habits.

A Little Tea, A Little Chat

It was a Saturday, a fine March morning.

Cotters’ England

Dr. Linda Mack had brought the five girls down to her Devon cottage in the car: it was June and the weather was fair.

Miss Herbert

As with the great Russian novelists. we are immediately plunged into the narrative as well as given a context in which to place the characters. Frequently this becomes a moral topography as well, as in the New York novels or the Parisian underworld of The Beauties and Furies. In their dense materiality, their concentration on the factual and the material, their insistence on reaching towards the inner life by exhaustive presentation of the outer, Christina Stead’s novels stand at the extreme opposite pole to those of Australia’s other great contemporary novelist. Patrick White’s division between the riders in the chariot and those outside, between the handful of the chosen and the rest of us, in its way a kind of aesthetic Calvinism, is in total contrast to the all-inclusiveness, the omnivorousness and the secularity of Stead’s vision.

The central character of The People with the Dogs is Edward Massine, yet another would-be writer (someday an article will be written on Christina Stead’s unwritten books) and the only one of Stead’s protagonists apart from Grant who is financially well off: we are given a detailed inventory of his financial assets by Miss Waldmeyer in the opening pages of the novel though, predictably this does not stop the novel from being to a fair extent concerned with the financial affairs of Edward as well as the other main characters. In contrast to the earlier two New York books, this one is marked by an almost Chekhovian sense of aimlessness, of people leading lives of quiet futility. Edward dithers not only at his writing (his talent is suggested by the fact that he came first at writing at school!) but also over whether or not to marry his girl who, eventually, leaves him in despair. Despite the quietly comic tone and affectionate treatment of the characters, a sense of melancholy foreboding is never far away. The deaths of Big Jenny and Philip Christy, Nell’s near starvation of herself to death, the background figure of Les Chubin who hanged himself for love set the tone of the novel hardly more than the comic proposal of Edward to Lydia at the end or the endless conversations that run across one another without meeting, as in a Chekhov play, rumours, pun apocryphal stories, complaints or intrigues.

Central to our sense of the superfluous, aimless existence of most of the characters is the motif of the dogs in the title. Many of the characters, most notably of course Oneida, lavish on them the love they are unable to feel or express for each other. Edward’s girl Margot accuses him with some justification of being more responsive to canines than to humans: ‘Yes, you can’t bear a dog howling, but you can bear a soul howling’, she tells him. Oneida, without doubt the most obsessive and fanatical member of the family in regard to dogs, indicates just how much they provide a core of meaning to her life: ‘She had a stout confidence and self-conscious movement,’ Stead tells us, ‘all the freedom of her ungirdled unembraced body, which was almost rich grace. She was full of movement, unrestrained, and it was perhaps the plenitude of this one love, her dogs, which had given this life to her small thick-set frame, which had no noticeable dwindling and spindling like other women’. Victor-Alexander comments of her shortly afterwards that she ‘substituted dogs for a moral and spiritual life, even a life of sensuality, talent: dogs were a deep-rooted and dangerous vice’. At one stage the family hear about a cure for old age that is highly expensive. ‘How angry Oneida was that dogs of the rich could have this treatment, perhaps, and her poor dogs not. “And then there are poor old men and women,” said Oneida.’ This. accurately reflects her order of priorities.

Like so many of Stead’s novels, perhaps more than any except The Man Who Loved Children, this is also pre-eminently a novel about family life, and about ,how family love can easily become a cossetting, destructive thing: ‘Am I turning my back on life or looking at life?’, Edward asks himself anxiously. However, in keeping with the sympathetic tone of the novel, The People with the Dogs ends on an almost unexpected note of reconciliation. Edward emerges from his lethargy long enough to marry and Oneida is given a new dog by her long-suffering husband Lou. The plea that Edward bravely makes for the way of life of the people with the dogs is implicitly given some weight by the novelist’s stance: ‘What harm do we do?’, he asks. ‘We’re creative sloth: what life ought to give but it doesn’t. The right to be lazy.’ Despite the many criticisms Edward himself has made of family life the novel closes with a strikingly posed tableau of all the family members: ‘In this moment, as in all others, their long habit and innocent unquestioning and strong, binding, family love, the rule of their family, made all things natural and sociable with them.’

By the time The People with the Dogs appeared, Christina Stead had written nine novels in less than twenty years. Since then she has published three more plus a collection of novellas over a period of approximately thirty years. Although she herself vehemently denies the suggestion, claiming that she has always written purely and exclusively for personal satisfaction, it is difficult not to suspect that critical and commercial indifference has had something to do with the marked decrease in her output. At any rate, the publication of her next novel, Cotters’ England, coincided with the revival of interest in her work that began in the mid-sixties with the attention paid to Randall Jarrell’s introduction to The Man Who Loved Children, the reprints of some of her novels in Australia by Sun Books and Angus & Robertson, and the two critical works on her by R.G. Geering. This interest has been boosted enormously in the 1970s by the rise of the feminist movement, which has also led to radical and belated recognition of other female Australian writers such as Barbara Baynton, Eve Langley, Miles Franklin, and M. Barnard Eldershaw (whom Virago plans to reprint next year).

The cosmopolitan nature of Christina Stead’s work is confirmed by the settings of the later novels – two in England and one in Switzerland, to add to her previous treatments of Sydney, Paris, London, Salzberg, Washington and New York. It is not so much that Christina Stead seems to put down creative roots wherever she goes as that she remains an attentive yet disinterested observer of every variety and species of human behaviour wherever it occurs. The later novels, especially, are above all works of observation; though largely devoid of the intensity of moral commitment that characterises The Man Who Loved Children and For Love Alone, they remain vivid and profoundly original works of art.

Christina Stead deals, comprehensively and wisely and unsentimentally, with whole areas of experience which had hardly begun to be opened up by other writers until the early 1970s, however much they have since become commonplace as subject matter. The variety and abundance of her characters and settings is as astonishing as the encyclopaedic nature of the jobs and activities she shows them performing. Collectively, her novels form as rich and crowded a world as that of almost any writer since Balzac.

Whether they are all ‘Modern Classics’ as most of these Virago reprints are described, is a debatable question. What is certainly true is that Stead carved out, in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, paths which other writers were to follow only years later. She is not only a pioneer but a pioneering giant. It is only now that, thanks to these handsome Virago volumes, that we can grasp the depth and voluminousness of her talent.