- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Footloose and Fancy

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

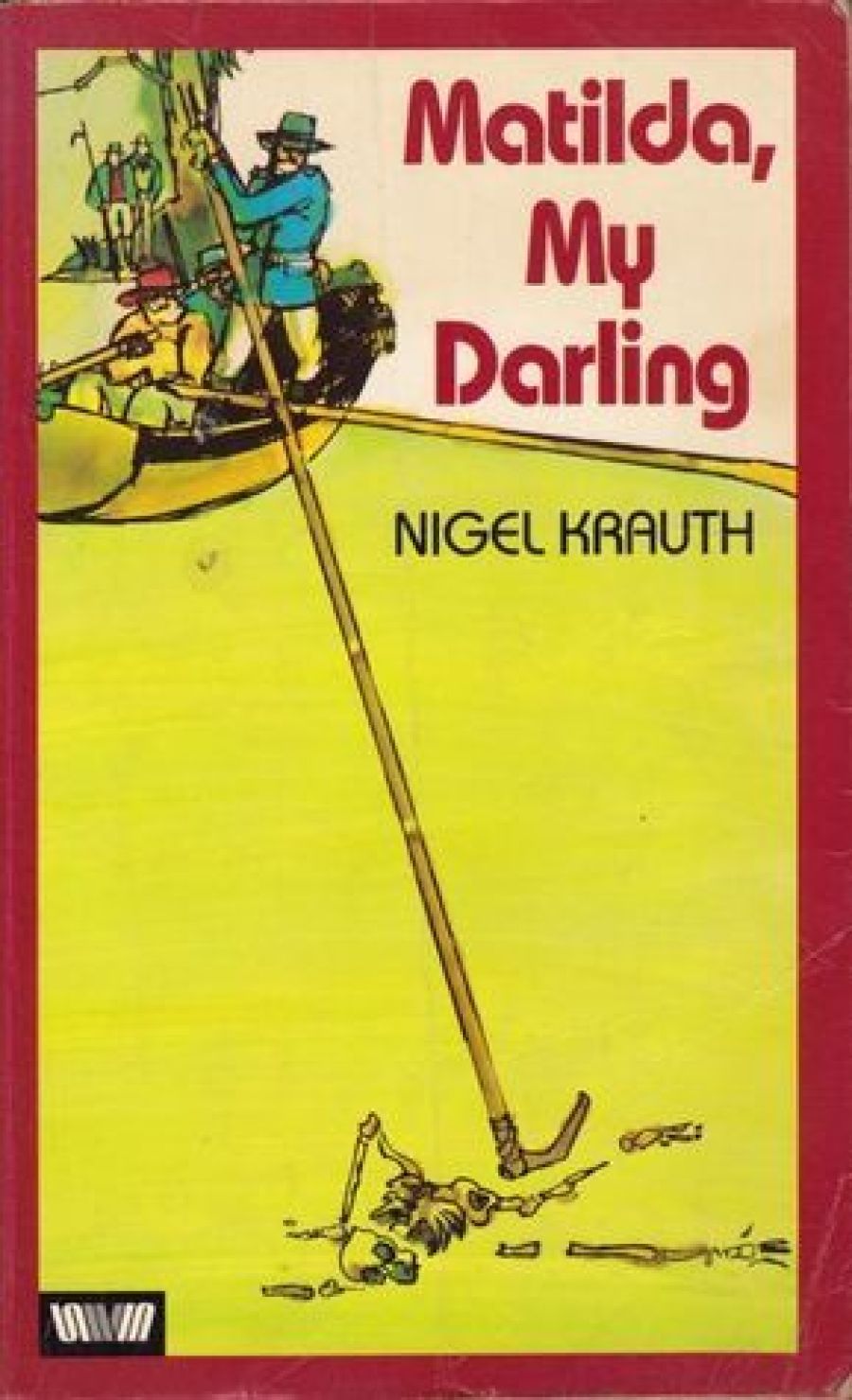

Nigel Krauth’s first novel is an intriguing blend of fact and fiction – or rather, a reworking of a little known set of factual events. As the novel explains, in 1895 the famous Australian poet ‘Banjo’ Paterson travelled to Queensland to visit his fiancée. Two events of importance occurred during that short period: Paterson’s engagement was broken off, and while there he wrote what was to become his and the nation’s most famous song, ‘Waltzing Matilda’. Paterson always refused to speak of the period in later life so that what exactly happened between himself and Sarah Riley remains unknown and Nigel Krauth feels free to speculate. There are ethical problems, I feel, in the fictional reconstruction of an historical personage and Krauth’s portrait of Paterson, while by no means wholly unsympathetic, is that of a man in many ways vain and narcissistic; certainly, it enraged the poet’s descendants to the point where they refused Krauth permission to quote the words of ‘Waltzing Matilda’ in his novel. Copyright does not run out until 1991 when, presumably, if the novel is still in print Krauth will fill in the blank spaces he has left.

- Book 1 Title: Matilda, My Darling

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $12.95 pb, 222 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Nevertheless, it is fair to say that the novel is hardly at all about Paterson the man as it is about a crucial period in Australian life, when a number of conflicts were fought out and, in the author’s eyes at least, the wrong side won, with consequences for Australian life which lave lasted to the present. Matilda, My Darling is a very ambitious novel, even if it doesn’t manage to fulfill all the enormous tasks it has set itself.

In Krauth’s ingenious reconstruction of events, a man drowns in a billabong and the unionists in Queensland – then engaged in a bitter war with the landowners – suspect foul play and hire a private detective to travel to central Queensland and investigate. The detective Hammond Niall travels under the guise of a policemen, Inspector Clohesy, with a further cover should he be found out as Laver, a man from the Colonial office. By accident he meets up with ‘Bartie’ Paterson, already Australia’s most famous poet, who is travelling to the same area to reclaim his estranged fiancée.

What happens over the next few weeks forms the substance of the novel, an account purported to be told by Sarah, the grand-niece of the former fiancée, as she works from newspapers of the time, from her grand-aunt's diaries and from her imagination. Krauth wants, I think, to show us how the events of 1895 shaped our own society in many ways. ‘Niall was willing to start out on an investigation only because he believed he knew where it would lead. To the tiny bud of a canker. The germ of a national epidemic.’ Something like this last claim is what the novel seems to be making insistently and in some ways puzzlingly. What is the nature of the criticism?

Predominantly, it is a question of class, and the competing rights of workers and pastoralists. As a background to the central drama of the novel there is a situation close to civil war between unions and bosses over the shearers’ strikes. Although the novel is relatively even-handed in its portrayal of this conflict, there is little doubt that Nigel Krauth sees the defeat of the unionists as a betrayal of Australia’s legacy. The unionists can be brutal – their leader Bright is viewed unfavourably and they steal a pastoralist’s beloved horse and cat it – but their basic cause is just. The land owners, on the other hand, are filled with a complacent conviction that the land and the right to rule are theirs by divine decree, the unionists arc scum, Nature is something to be exploited and women are fondly regarded members of a lesser species. The wise Sarah puts it very well when she comments of the unionists, ‘I believe I can understand a man’s sense of dispossession when he sees himself sweating on his country's land, while having no say in how it is governed. He feels like an animal, so he acts like one’.

All of these themes are closely interwoven in the novel. To take only one of them, the men’s treatment of women in the novel has clear parallels in modern times. The central failure is that of Paterson in his relationship with Sarah who finally rejects him for the life of a recluse but prevalent in the assumptions of all the pastoralists is a quite fallacious assumption that the women are incompetent to perform the tasks they themselves undertake.

Krauth also has a nice line in deadpan comedy which comes out in the squatters’ relationship with their environment. One of the best scenes in the novel is an impassively described hunt in the best English style – except that the quarry, a dingo, escapes from the dust-engulfed hunters. Or there is this description of another absurdly derivative ritual: ‘There were songs and recitations, violins and a Frenchhorn, a mellifluous barber-shop trio and, for light relief, a magical act by an old veteran of the area who had to be assisted when a penny he deposited under a hat on a table reappeared stuck between his shoulder-blades where he could not reach it’.

Matilda. My Darling is an intelligent and for the most part well- written novel, even if it doesn’t always convince one that the events it described led directly to the faults of contemporary Australia. Sometimes, the writing has a tendency to show off, as in the rapid and gratuitous cutting among Niall’s various identities, the scenes in dialogue form, and the bouts of rhetorical repetition. I also enjoyed the following sentence – ‘the magnet of her beauty prickled the iron in his soul’ – in which the metaphors are not so much mixed as pureed.

Comments powered by CComment