- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Keith Willey died on 6 September 1984. He had just submitted the manuscript of what was to be his last book. A study of Australian humour in adversity titled You Might As Well Laugh Mate, it summed up the man, not least in his last days. Sardonic, self-effacing, unashamedly Australian.

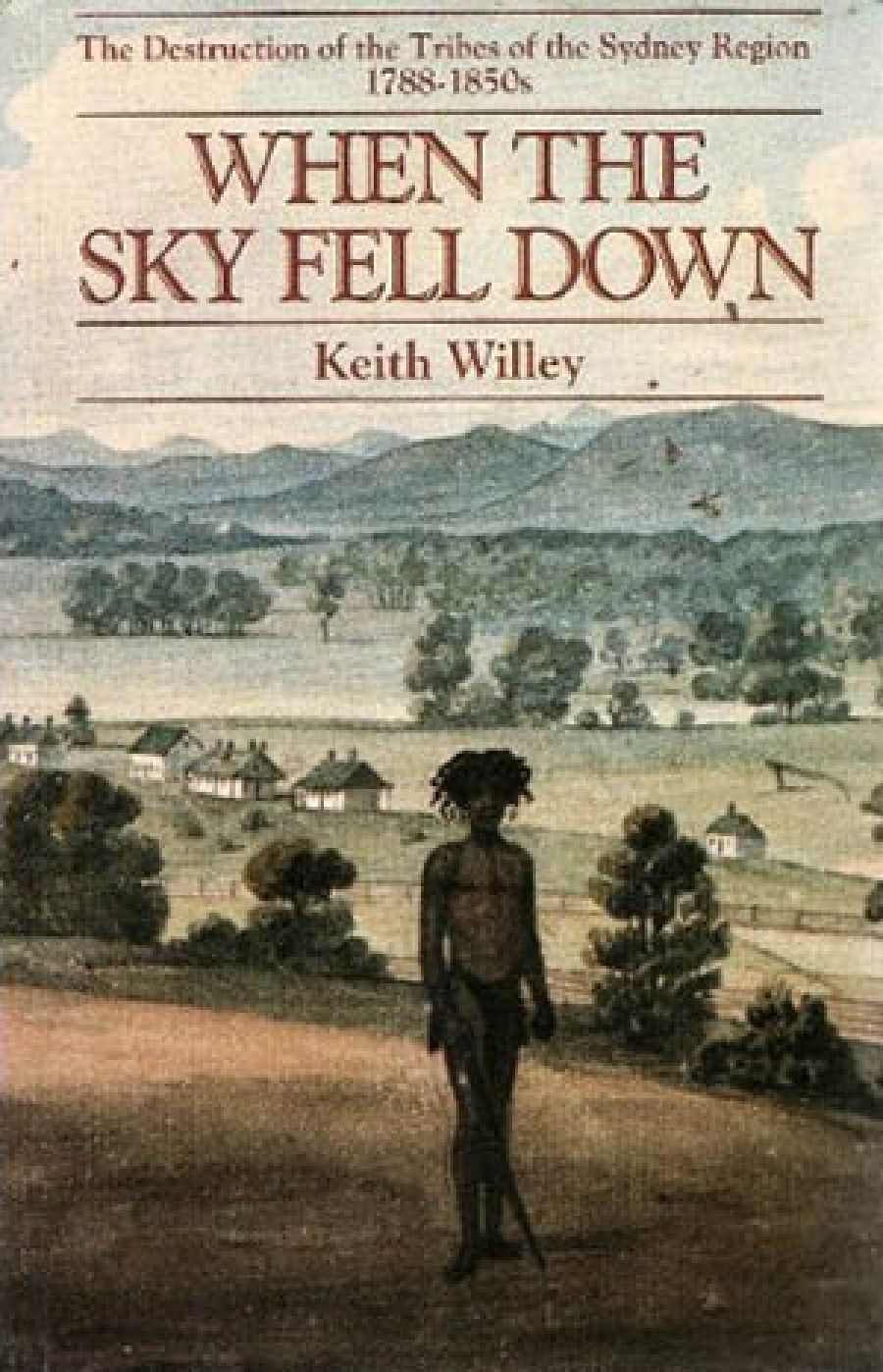

- Book 1 Title: When the Sky Fell Down

- Book 1 Subtitle: The destruction of the tribes of the Sydney region 1788–1850s

- Book 1 Biblio: Collins, $8.95 pb, 232 pp, index

Keith Willey was born at Boonah in south east Queensland in 1930. He always wanted to write and in 1948, after three stultifying years ‘in the bank’ and a number of publishers’ rejection slips, he entered the world of journalism which then seemed the only avenue for an aspiring writer.

As a journalist he travelled widely and adventurously. Serving his apprenticeship in Brisbane and Hobart, he moved to Adelaide, married (1953), became editor of the Centralian Advocate (1955) and worked briefly for the Melbourne Age (1956). His time in Alice Springs, however, has caused the outback to enter his blood and shape his philosophy. He spent a further seven years (1957-1963) in the Northern Territory, the last eight months as a professional crocodile shooter. As ‘Our Man in Port Moresby’ for the Australian and associated papers in 1964, he foot-slogged with a Pacific Islands Regiment along the Irian Jaya border and, joining a croc hunting party, made several ‘illegal’ forays into Indonesian territory. For the Sydney Sun he covered the hanging of Ronald Ryan (January 1967), the drowning of Harold Holt (December 1967), the border fighting in Israel and race riots in Singapore (1969), and the Vietnam War (1970). His reporting won him the Walkley National Award for Journalism on three occasions.

Yet reporting was not enough. Keith always had an eye for the larger picture, the larger story, but, with the journalist’s concern for his readership, always focussed on the personal and human. His years in the Northern Territory produced Eaters of the Lotus (1964), the personal adventure Crocodile Hunt (1965), and the biographical foray into oral history Boss Drover (1971). His brief to report the changing face of New Guinea saw Assignment in New Guinea (1965). The rescue of castaways on the Tongan Island of Ata was extended in Naked Island (1970). A stint on the Cairns Post resulted in Crown of Thorns (1972).

Above all, Keith was fascinated with the lives of ordinary Australians, especially but not exclusively in the outback. It is this link with the people with informs the stories in Tales of the Big Country and Ghosts of the Big Country the best of which is most certainly his sensitive eye-witness account of the last moments of a convicted murderer in Pentridge Gaol. It has fallen to few Australians (and since 9 January 1967 to none) to see the cold administration of death: it moved Keith deeply and made him love life all the more.

He believed strongly in the adage: word hard, play hard – his life was a regimen of writing, swimming, and social drinking. In addition to his full-time journalistic duties, he always worked simultaneously as a freelance writer on his own or commissioned works; he produced twenty-one books in as many years. In thirty-one years, of married life there was only one holiday in which he did not find time to write; even when suffering temporary blindness in 1965 he dictated a book to his supportive wife, Lee; except for the last year or two he never slept more than five hours a night. But he still found time for family and friends.

In his youth Keith was a potential champion swimmer. In later years ever river, lake or ocean beach was a challenge. To travel across country with him was to experience a Cook’s tour from waterhole to waterhole. It was his way of coming to terms with the Australian environment.

It was his ambition to have a drink in every hotel in Australia for he was fond of the public bar and its attendant life. It was part of his search for an Australian identity. He would spin tall yarns with the best and indulge his repertoire by bush songs, being unabashedly devoted to Slim Dusty. When Darwin barmaids were criticised by a visiting Victorian as ‘illtempered, female scorpions’, Keith leapt to their defence:

When Mum lets him off the muzzle

And he wants a quiet guzzle

The drinker downs his bite of grub

And staggers off toward the pub

To seek that mistress of her trade

The buxom, bouncing bar-room maid.

Keith left school in 1945 and thirty years later set about ‘repairing his education’, obtaining an honours degree in history from ANU and working towards his doctorate. He was drawn by Australian history and folklore. The Drovers was published in 1982 and his chapter in The Stockman (1984) is deservedly the most critically acclaimed of the contributed chapters.

In 1983, Keith accepted a lectureship in Journalist at the Darling Downs Institute of Advanced Education. His personality, his experience, and his ability to get jobs for graduands made him popular with students. Teaching was a new experience for Keith: he hoped to produce a practical textbook for journalism and the autobiography of a working Australian journalist was taking shape at the time of his death; both will be sadly missed.

Keith Willey was a man in love with Australia. His life was a celebration of being Australian. His writings were a search for ‘Australianness’ in the tradition of the legend, the bush ethos, and the sentimental bloke:

We’ll drink on till our number’s up.

Then write upon our coffin clear.

‘Here lies a man who loved his beer’.

Death’s round the corner. Sure. But so’s the pub.

Comments powered by CComment