- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: True Crime

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Great Mint Swindle was one of the most outrageous frauds in the history of Australian crime. On 22 June 1982, the closely guarded Perth Mint handed over, without a murmur, $650,000 worth of gold bars, which were never to be seen again. Not a shot was fired, not a person threatened. It was all done with three fake building society cheques, which the Mint accepted without question. The mastermind behind the ingenious swindle never showed his face.

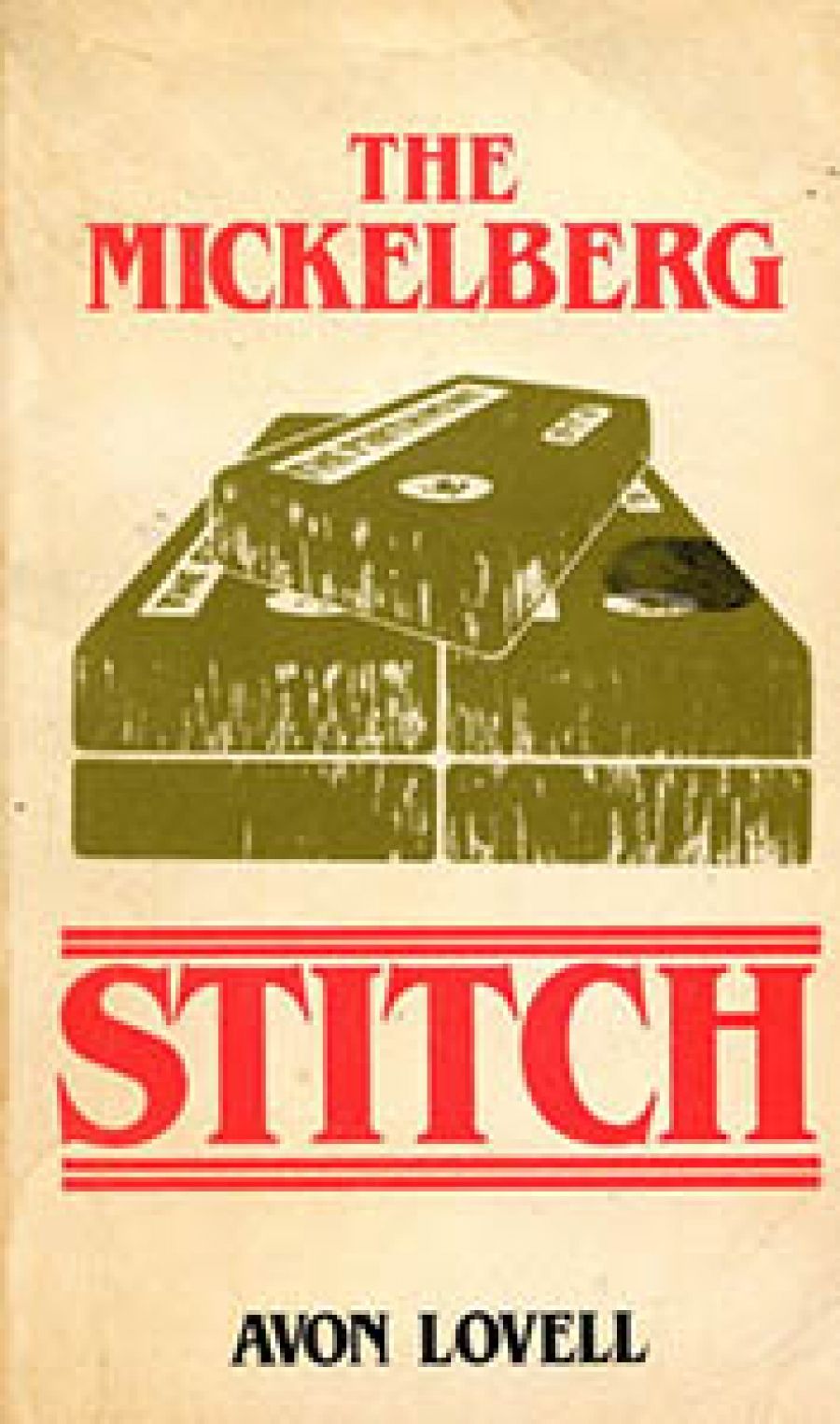

- Book 1 Title: The Mickelberg Stitch

- Book 1 Biblio: Creative research, 285 pp, $8.95

By telephone he ordered the gold from the Mint, arranged for security guards to collect it, rented an office and hired a secretary to give the guards the cheques and receive the gold, hired a courier to pick up the bullion – ostensibly boxes of machinery – and deliver it to Jandakot Airport. From Jandakot the gold disappeared without a trace, despite an intensive police search which has ranged underwater, underground, and overseas.

On 4 March 1983, the three Mickelberg brothers – Ray, Brian, and Peter – were convicted of swindling the Mint. Brian was later acquitted on appeal but Ray (39), an ex-SAS Vietnam hero, and Peter (25), his fresh-faced young brother, face gaol terms of 20 and 14 years.

In The Mickelberg Stitch, author Avon Lovell takes a fresh look at the Great Mint Swindle and at the evidence that convicted the Mickelbergs. It is a frightening book, one which would make a rattling good novel if it were not based on fact.

Is it possible that the Mickelberg brothers are in gaol for crimes they did not commit? Lovell clearly believes them when they say they were set up by the police, that they had alibis for the day the Mint was swindled, that they are victims of a monstrous injustice. The impact of his argument is weakened by his obvious partisanship, but even so this is a book which cannot be ignored.

His most telling chapter deals with the crucial fingerprint on one of the three fake cheques which were used to obtain the gold. Fingerprint experts testified in Perth’s District Court that the print was Ray Mickelberg’s. It was the most damning piece of evidence at the trial. If Ray’s print was on one of the cheques, how could anyone believe his story that he had nothing to do with the crime? Judge Heenan told the jury: ‘You may safely accept that a fingerprint is, in effect, an unforgeable signature.’

Now Lovell, a freelance journalist who spent fifteen months investigating the case, has come up with four internationally respected fingerprint buffs who say that the judge was wrong. From London there is Scotland Yard veteran Reginald John King; from Scotland Malcolm Watson Thomson; from the US ex-FBI man George C. Bonebrake and ex-Army investigator Robert Dale Olsen. All four agree that not only is it possible to forge fingerprints, but that the print on the Mint cheque was probably forged from a silicone rubber mould of Ray Mickelberg’s right index finger.

The mould would have been easy to come by. One of Ray Mickelberg’s hobbies was casting hands, in brass, plastic, rubber, even clear perspex. There were twenty or more hands in the sitting room of his Perth home when the police paid their first visit, and several were confiscated for inspection.

Hilton Kobus, a forensic scientist who gave evidence at the trial, told author Lovell: ‘I just find the whole thing too shattering to comprehend. You have to believe the people producing the fingerprint evidence, but if they are shown to be dishonest, the whole system just dissolves. Terrible. It is in the interests of science to follow the whole thing through to its logical conclusion.’

What would have been left of the crown case against Ray Mickelberg if there had been no incriminating fingerprint on the cheque? Circumstantial though it was, it added up to a solid body of evidence which would have taken an extraordinary chain of coincidences to create if Ray Mickelberg had indeed nothing to do with the Mint swindle.

The police were led to the Mickelbergs in the first place because two of the three forged cheques presented to the Mint had on them the number of a Ray Mickelberg account in the name of ‘Peter Gulley’.

‘Gulley’s’ address, 144 Barker Road, Subiaco, turned out to be a vacant block, but by checking old SEC accounts the police found that it had formerly been occupied by ‘P. Mickelberg’, the boys’ mother Peggy, who used to run a boarding house at that address.

At his trial Ray admitted that ‘Peter Gulley’ was one of a number of aliases he had used for different accounts. It was for tax reasons, he said. He tried to explain away the Gulley account number on the two fake cheques by saying that he had lost his passbook on May 27, nearly a month before the Mint swindle. Anyone could have found the passbook and used that number, he said. This was a theory which was soundly demolished by the crown prosecutor, Mr Ronald Davies. He pointed out that it had been weeks before May 27 that the blank cheque forms used in the swindle had been stolen in two separate burglaries. It would have been an amazing coincidence if the person who found Mickelberg’s Perth Building Society passbook had been the very same person who had stolen the PBS cheque forms.

‘Hopeless, you may think,’ he told the jury. ‘It relies on the proposition that you people came down in the last shower of rain.’

Comments powered by CComment