- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

C.J. Koch in this powerful and evocative novel, The Double Man, has applied a psychoanalytic model of human personality to fairytales and the fantastical world of myth: the pursuit of illusion as reality. Its ingenious double life is that of a modern-day fairy tale coupled with the face of 1960s man, paralysed with the despair of his era: its inability to cope with the breakdown of shared values and beliefs. Richard Miller is both the prince of the archetypal fairytale and the prototype of modern man trying to create a private reality out of ancestral beliefs. The Double Man recalls W.B. Yeats’s dread of the ‘rough beast…its hour come round at last’, and the warnings of Goethe who foresaw a time of such chaos: when odd spiritual leaders would emerge and man would turn full circle to find popular truth in ancient myths and legends.

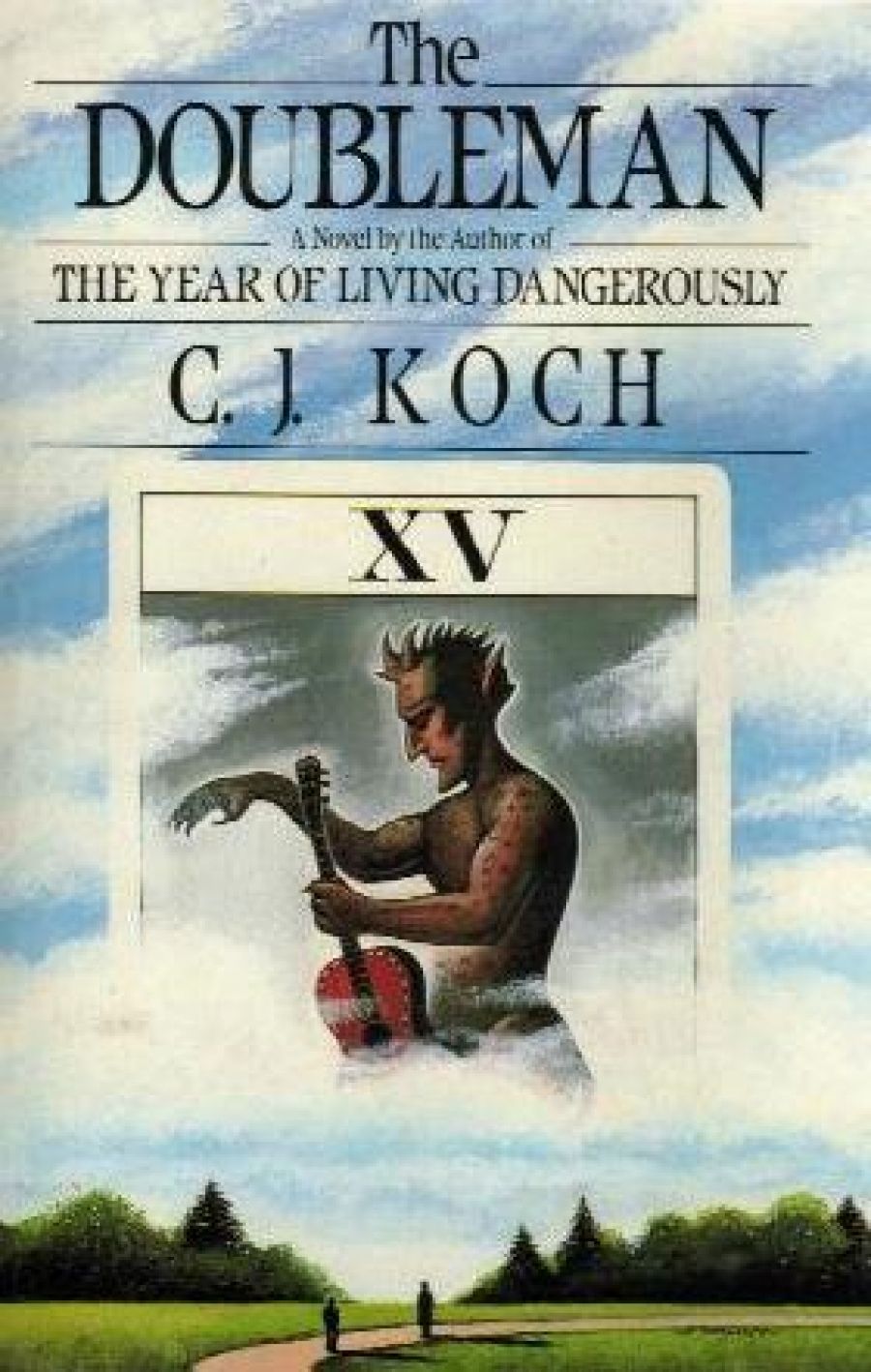

- Book 1 Title: The Doubleman

- Book 1 Biblio: Chatto & Windus, 326 p, 48.95 0 7011 2945 X

Years later the three meet again in Sydney. Miller has become a successful broadcasting producer and Brady and Burr have established themselves as an unconventional folk-singing group. Music becomes the key which locks the three together: Miller, because through it he can finally give his ‘fantasies flesh’: Brady, because he is its natural instrument: and Darcy, because it serves him as an instrument of power. When Miller’s Estonian wife Katrin joins the group, the Rymers emerge finding their inspiration in the ballads of faery and the supernatural. They become an extraordinary success story, created by Darcy and Miller and made real by Katrin and Brady. But the spell of Broderick has been replaced by the shadow of Darcy, his disciple, and the magic that has created them finally leads them to disaster. Brady escapes: Miller finds his reality, ‘shriveled, savorless and dead’, and Darcy is left in a frenzy of thwarted ambition.

Fairytales, occultism, myths, Catholic cosmology, and medieval romanticism become the rich territories within which Koch’s crippled man must work through his conscious, pre-conscious and unconscious dilemma. As does Bettleheim in his cult study, The Uses of Enchantment, Koch chooses the scope and coherence of the fairytale, in particular, as a landscape in which his child can ruminate upon his inner pressures. Bettleheim argued that children not given access to fairytales would have major difficulties in working out their lives, without their sub-conscious messages sorting out their unconscious worrying. But Bettleheim’s child is ‘healthy’ and matures unconsciously while yet a child; Koch’s child refuses to let go and moves into manhood enslaved by the dream of illusion.

‘‘All enthrallment is an arrested past: the prolonged, perverse childhood from which some souls never escape.’ Bettleheim’s children are victims of a psychological experience; Koch’s man is an active agent in its formation.

Richard, the child, sees himself as being both saved from total paralysis, and saved by it. Only those who have truly been broken and who have recovered, he argues, can enter into the life of dream. And so the prince of fairytale is born: the chosen one who can scorn the ‘crude ordinary world’ about him. As archetypal prince, he then begins the painful path to self-realization -by ordeal -encased in the magic number seven. From the age of twelve to eighteen he endures the ‘penal servitude’ of a Christian Brothers’ education, seven years of penance.

The initiation rite into the second stage demands abandoning his crutches and undertaking the physical agony of a grueling bike ride to his uncle’s farm, ‘a soaked animal in harness’; to arrive at new spaces, ‘wild and free’, and the birth of a new bondage in the shape of Deidre Dillon. He is now able to enter into the conspiratorial realm of the Otherworld; tutored by Broderick. Seven years later, at twenty-five, he is ‘freed’ symbolically by the Island itself.

Now, throwing away his walking-stick he leaves Tasmania forever. The next seven years are spent in Melbourne until he learns the secret of this ordeal: that he must create illusion, not be one of its tools. The final trial is the most vicious. Miller arrives in the ‘city of dust and dreams’, Sydney, where once again he undergoes a painful and frightening initiation. ‘I wasn’t quite normal … the true and deceitful were merging, present and past blurred into each other.’’ Present and past do come together in the ‘wistful dream of continental Europe’, Katrin, his future wife. By the close of the seven years we see Miller pierce the skin of his illusion to find his first blurred image of reality.

As a conclusion to a true fairytale, the ending is unsatisfactory, for Miller has had his truth forced upon him-rather than having won it. Darcy may be left in a fury and frustrated rage, (like the bad queen who must dance forever in red hot shoes), but Miller is left stupefied and exhausted rather than rich with insight.

The conclusion makes more sense when placed in its time. The sixties with its shattered dreams, unsatisfactory philosophies, war, suffering and denial of an all loving God afforded no easy solution. If reality can never be known in any absolute way, ‘All the world’s an illusion’, then it is appropriate that a man of this age should find his approximations of reality under the gauze of drugs. Music becomes the metaphor of the times – the jangled combination of heavy guitar work and ancient ballads. Music is the characters’ ‘Ticket to Ride’ their chance to escape – for they are all trapped –crippled – in some form or another. Deidre Dillon can only love the ‘crippled and callow’’: Katrin cannot move beyond her memories of her lost Europe: Darcy rejects all human feeling in the pursuit of power and Brady allows himself to be carried along in the surge of it all because he is too weak to resist.

The Double Man is a complex and exciting novel of ideas. The structure of the novel is clearly ambitious but seems to lose some of its coherence as it works its way to the conclusion. The language that informs the land itself and the enchantment of faery is magnificent. It is a pity, to my mind, that Koch is not as convincing when he writes about music because this constitute a major metaphor for the enthralment.

Comments powered by CComment