- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Influence spotting is one of the major preoccupations of traditional art history. Important and necessary though the practice may be, I sometimes suspect that it is employed to keep art history the preserve of the specialist and to deny access to the general reader. How refreshing, then, to be confronted with a scholarly Australian art history book that explores the artists’ subject matter and its local context rather than the derivation of the artists’ styles.

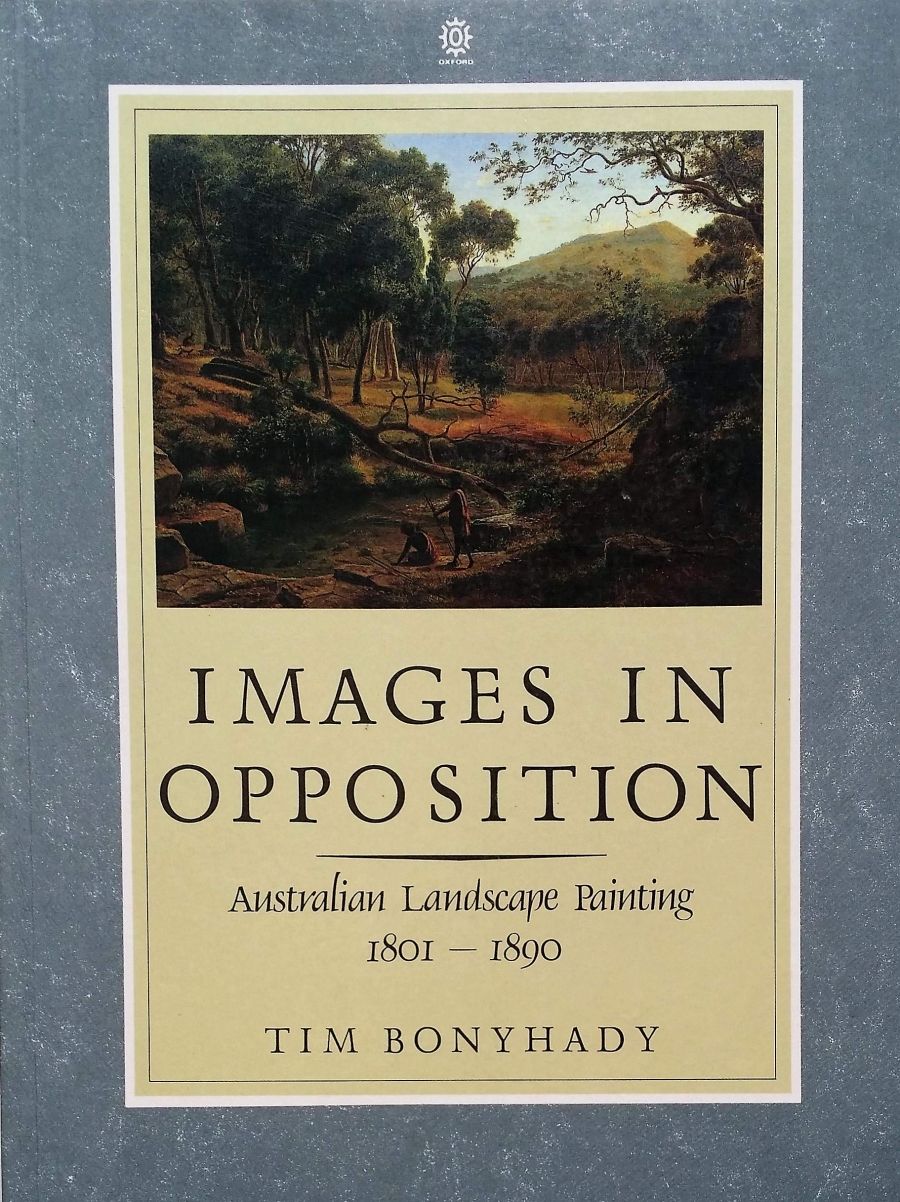

- Book 1 Title: Images In Opposition

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian landscape painting 1801–1890

- Book 1 Biblio: OUP, 192 pp, $45.00 pb

After assigning pictures to various subject categories, Bonyhady concludes that the development of landscape painting was remarkably little affected by changes in land use in the colonies. He demonstrates that it is rather foolhardy to read paintings as accurate visual ‘documents’ of existing land use or social conditions. This is not to say that a social and political interpretation of the images cannot be reached, and Bonyhady shows the way by painstakingly reconstructing the original context of numerous paintings. sometimes with surprising results. For example, a John Glover picture, portraying the Aborigines in an arcadian world before European settlement, was originally intended to be engraved as a frontispiece of a book George Robinson was writing about the conciliation of the Aborigines. In fact, Robinson was largely responsible for leading them into captivity!

That painters frequently clung to stylistic and subject conventions in the face of changes in land use or social circumstances does reveal, even by default, something of their aspirations and, possibly, those of their patrons and audiences. Few, if any landscapes were judged by critics in terms of their political content and it was not so much a matter of who actually owned the land portrayed as of who was seen to occupy it according to the subject convention. As Bonyhady notes, no major European artist chose to visit Australia during the nineteenth century, but one should not conclude from this that our colonial artists necessarily belonged to the second rank. Their very presence here often indicated a personal sense of adventure. If wilderness scenes were part of the stock-in-trade iconography of nineteenth century romanticism, then artists such as von Guerard and Chevalier endured considerable hardship and danger in order to experience and record them first had.

There is much original research material in this book (ably supported by copious end notes) to arouse and sustain the interest of the specialist in the field, but the book’s real importance lies in the major propositions it raises regarding the nature of colonial landscape painting. It would be a pity if the fact that several of the pictures discussed might also fall into another category from the one Bonyhady assigns them, were to distract nit-picking critics from the larger issues. A much more fruitful enterprise would be to examine factors which link and underlie Bonyhady’s different subject categories. Here one could suggest the colonial artists’ sense of the age and primeval grandeur of the Australian continent – a concept which might be equally located in images of Aboriginal arcadia, in wilderness scenes, in von Guerard’s and Chevalier’s quasi-scientific concentration on geological forms, in Marcus Clark’s famous passage on the ‘weird melancholy’ of the bush, and even, perhaps, in Buvelot’s love of our ancient-looking gum trees, with their gnarled, grotesque branches. Similarly, more weight could fall on the consolidation of art institutions and transport in Australia from the 1870s onwards. This helped establish a bourgeois art audience who found Buvelot’s images of the ‘familiar countryside’ more amenable than the romantic, grandiose subjects of von Guerard.

This stimulating, scholarly book gives hope for the future of Australian art history.

Comments powered by CComment