- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This book is a collection of papers from the first Aboriginal Writer’s Conference, held at Murdoch University in February 1983. Despite the long (unexplained) lapse between the conference and the appearance of this book, the papers raise a number of urgent and complex problems, for writers and commentators.

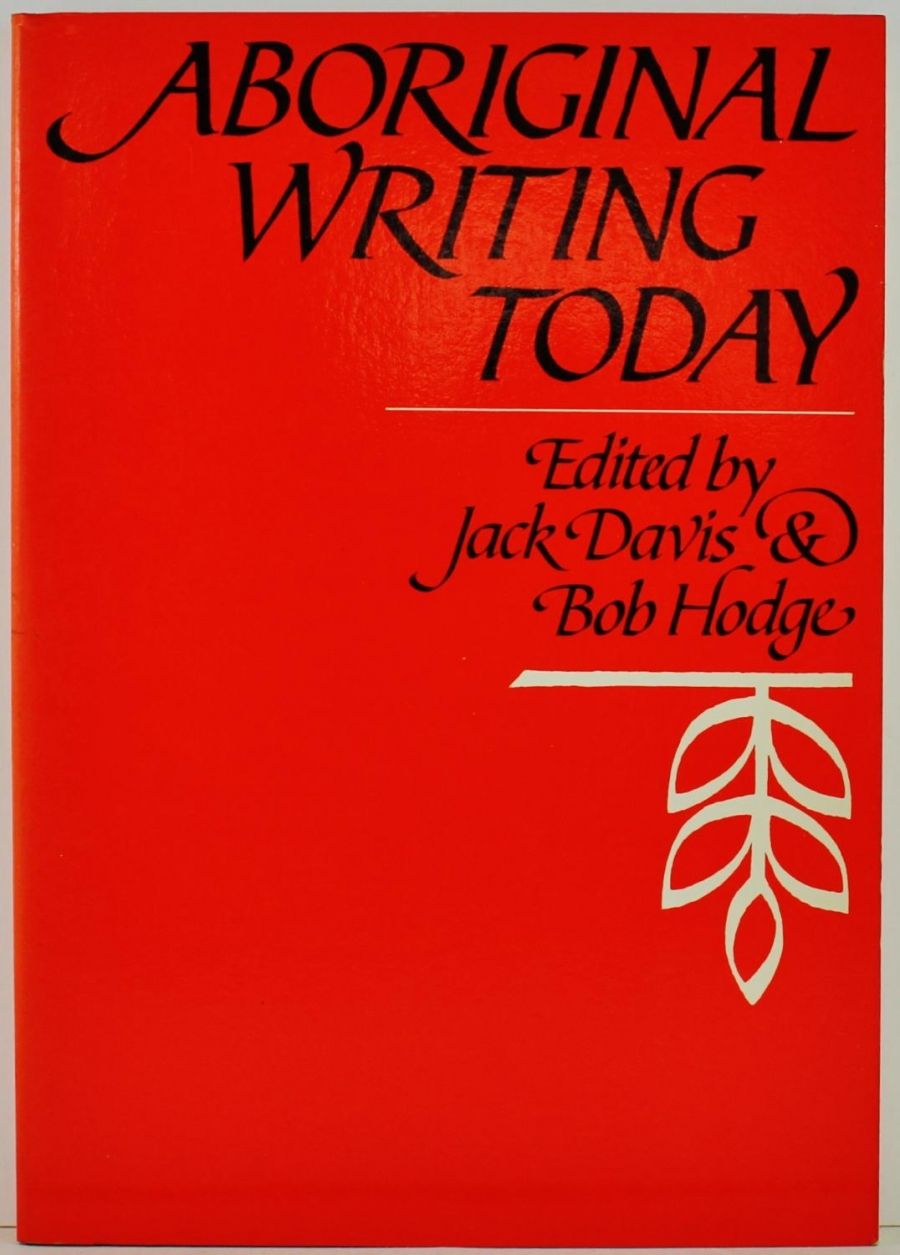

- Book 1 Title: Aboriginal Writing Today

- Book 1 Biblio: A.I.A.S. Canberra, 112 pp, $9.95 pb

Despite the sometimes extravagant charges which accompany this theme, this is a real issue, one which demands an answer from the broader Australian literary community – even though several speakers express the wish to remove Aboriginal writing entirely from the community. Gerry Bostok deals extensively with this in his paper on black theatre:

we never worry ourselves about what critics say ( or I certainly don’t) because we’re ploughing new ground . . . what they have to say about me, or my actors that I’m with, or black theatre in general, doesn’t interest me one iota. It may interest people in white society, and in white theatre backgrounds, but it certainly doesn’t interest me …

The same thought surfaces in a discussion question to Cliff Watego:

you’ve got to be careful about white academic thinking because you’re destroying what a lot of people have put together to be enjoyed, rather than pulled apart ... we must bring our people back out of the white institutions, and back to their communities.

Not all the speakers agree with this proposition. Colin Johnson (Wild Cat Falling, Dr Wooreddy …) concludes a very interesting paper with a response to a statement on Aboriginal control of publication:

we’re taking the literature in a vacuum here ... you have to sell it in a capitalist country, you sell the product of your labour. Now Aborigines are to a certain extent fortunate that they can get published through grants and things like that, and the majority of people in Australia who are writers cannot . . .

With regard to the critics, Johnson argues: ‘if (Bob Bropho, Fringedwellers) didn’t like criticism of his book he shouldn’t have published it. It’s public property now. Once the, book leaves the author it is there to be criticised by anyone who wants to, which is what happens to my books.’

With one or two exceptions, then, the speakers at this conference expressed profound dissatisfaction with the reception of black literature by white critics.

The problem lies, of course, in the application of European critical technique to literature which has as one of its sources the traditional black literature, with its use of simple, reiterated phrases as the fundamental mode. This style, discussed in Catherine Berndt’s paper on traditional Aboriginal styles and themes, is illustrated by three stories told in the traditional manner by Daisy Utemorrah, Mona Tur and Daphne Nimanydja. While there may be serious doubts about the application of conventional critical technique to Aboriginal literature, to do otherwise might lead to charges of patronising black writers – ‘this is by an Aboriginal and hence we have to make allowances’. It is my feeling that the latter approach is far worse than the former. It’s something of a no-win situation for the critic, even the critic with the very best intentions. The reception of Roland Robinson’s criticism of Kath Walker’s poetry is a good example:

(Robinson wrote), that her poetry is ‘painfully elementary’ and that ‘she needs to unlearn literary influences’. This kind of criticism challenges Kath Walker’s right to choose the forms that are appropriate to her purposes and fails to see how powerful and effective her poetry is. There seems to be a punitive idea of what an Aboriginal voice must sound like, which is to be imposed on Kath Walker as though she would not know what is proper for Aboriginal poetry unless a white critic told her.

This is not entirely fair to Robinson, who is arguably the best white advocate for Aboriginal myth and poetry which Australia has produced; nor does it take into account Robinson’s notorious impatience of any poetry which allows ‘being poetic’ to get in the way of the poem. However, if that is the perception of black authors, then clearly there is a yawning gulf between blacks and whites in Australian literature.

So it’s worth reading, this book. Some of the essays, especially those which are unabashed political manifestos, are disconcertingly generalised and intemperate – although one has to concede that the political basis of black writing in Australia (especially urban writing) is given focus in these papers. Behind the polemic, the half-truths, the distortions and anger, there is a clear, unequivocal message: the Murris and Kooris are talking – maybe we should shut up and listen awhile.

Comments powered by CComment