- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Chronicles of Migration

- Article Subtitle: Highs, lows and all

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Maria Lewitt is, if anything, a writer in the realistic mode, and she might be among the last to see her own work – and characters – in either symbolic or allegorical terms, For, their fleshbone-and-blood individuality and tangibility aside, the major protagonists of her autobiographical novel No Snow in December – sequel to her earlier prize-winning Come Spring – could well be seen to constitute a spectrum. representing the migrant’s coming to terms with the land of his/her adoption.

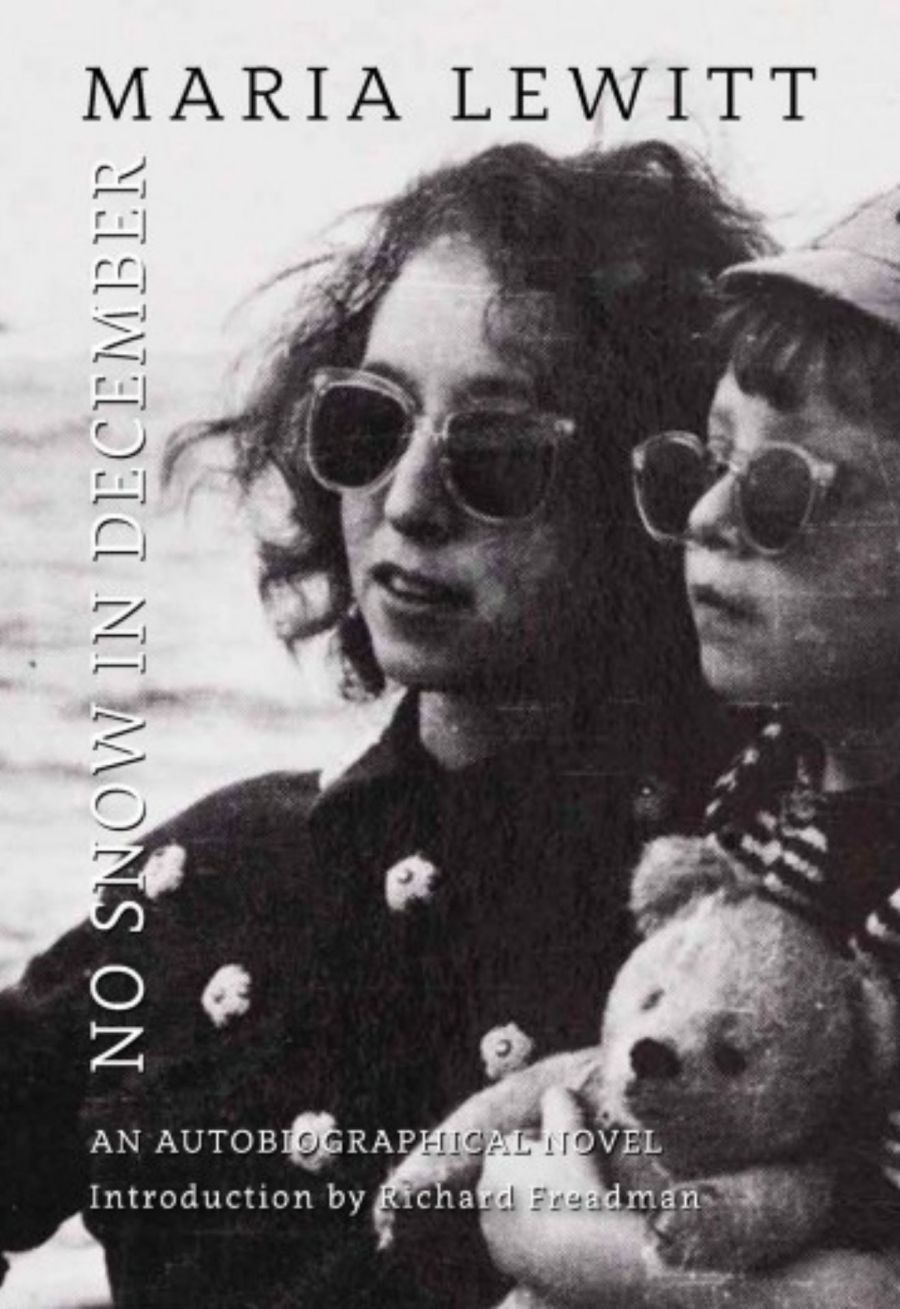

- Book 1 Title: No Snow in December

- Book 1 Biblio: Heinemann, $16.95, 283 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

At the other extreme is Julian, lrena’s husband, a British-trained textile engineer originally from Lodz like herself, who acquiesces to whatever is dished out to him on arrival in Australia, who accepts whatever menial job is on offer, and makes quick peace with the fact of being passed over for a position commensurate with his abilities because ‘Australian workers won't tolerate a foreigner stepping into a managerial position’, saying ‘It doesn’t worry me ... after all, we’re migrants, we can't expect the same treatment as the native-born.’

There is tragedy of a sort inherent in both of these extreme positions, the one because it bespeaks a life intended for better things (enterprise, vision, music, loving family) reduced to rancour, perpetual recrimination and nightmare – the delayed, unseen, sequelae of a war which was to destroy a generation of souls into perpetuity no less than lives; the other because of the abominable waste incurred, because of the very acquiescence of a man resigned to being less than his talents, ambitions, potential and training have equipped him for (a state of things which, thirty-five years on into our own day, has not all that greatly changed, where immigrant engineers, doctors, lawyers, musicians and journalists must serve their apprenticeship in this country as orderlies, technicians, process workers and fruiterers, and be expected to be grateful even for this).

Ranging between these extremes along the spectrum, tossed between recrimination and docile acceptance – indeed, even rejoicing in her new land – is Irena herself. On the one hand, she says ‘Here in Australia, I have everything. I should be ecstatic with happiness, but I am not. Is it the remoteness, loneliness, estrangement?’, and, as if to underline these, '[My son is] growing in an artificial environment. No-one is being born; no-one is being taken care of; no-one is in need of attention, advice; no-one is gravely ill; no-one dies’; yet, on the other, she delights in – and is amazed by her own capacity to delight in – everyday events: ‘… in a sunset, the stillness of an autumn day, the geometrical perfection of a cobweb between two rose-bushes in our “back garden” as Michael [her second son] calls our backyard’; and adds ‘Sometimes I think our appreciation is greater because of what we went through’.

Then again, she bemoans Julian wasting his productive years in filling fridges with milk and soft drinks in the milk-bar they take over, as earlier he has done in assembling textile machines and in joinery and later in a cake-shop, yet is she able to say ‘While other countries were considering what to do with post-war refugees, Australia let us in, gave us work and the promise of a more stable future. It gave us back dignity. I’m free, my children are growing into self-confident people, free from complexes.’ All this after being duped by an unscrupulous doctor into believing that her son; once suffering from TB, is not, yet cured; after being coaxed – mercifully, unsuccessfully – to give up her child for adoption that she may the more easily attain to ‘an acceptable standard of living’; after being brow-beaten into an abortion; after being subjected to the gratuitous insensitive tirade of a Welfare man bewailing conditions in Australia during the depression and the war years when she, Irena, has – body, mind and soul – been through it all in the actual arena of turmoil; along with other, if lesser, unaccustomed encumbrances such as corporal punishment in schools, skin on hot milk, adults treating children as lesser people, rhetorical manipulation of issues and beliefs, hypocrisy, and lack of humour.

For all that, while Irena dips periodically into brooding pensiveness and nostalgia, yet does she repeatedly regain her basically resilient and optimistic buoyancy. Though the Australian terrain is not that of Poland, yet are there times, as in Mount Buffalo, when she falls in love with it and is inspired as if by Beethoven’s Ninth and soothed as if by Vivaldi’s Four Seasons; while she encounters episodes of indigenous haughtiness, and her son is tried by anti-Semitic taunts at school, yet ate these redeemed by the deeper human decency shown by her Australian neighbours, by the school’s headmaster, and by her customers and acquired Australian friends.

As a migrant child of migrant parents come to Australia in the same post-war migratory wave, this reviewer can well vouch for the authenticity of Maria Lewitt’s story, highs, lows and all, right down to such touches as seeing his own parents learning English from such books as the John and Betty primers (having read Tuwim, Shakespeare and Mickiewicz back home), or being witness to their long and countless hours accumulating the pennies from the sale of cheeses, eggs and hams from behind a shop counter, piecemeal building up a tolerable life, as also to the generous advice, goodwill and support of neighbours set against the long-pervasive suspicion of hostility lurking in the wider society beyond, and to the acknowledgement of this country’s freedoms, tolerance and laissez-faire go-as-you-please ambience coupled with an aching homesickness for family, past familiar surroundings and cultures back home but becomes forever and irretrievably lost.

Maria Lewitt’s story is, of course, her own; and she tells it with lucidity, sensitivity, frequent dashes of humour and, above all, humaneness throughout. But more tellingly, it speaks for a generation as well, and while it is far from being didactic in intent, the reader would be well repaid by an open-minded and sensitive reading of the work if he would understand the lot of the migrant who has been uprooted in a totally inconceivably-different land, who has experienced the ignominy of being so often second class, who has never attained – will never attain – to that which birth may have promised, yet who, after all the turmoil and anxieties over work, family, meaning, isolation and the different utterly alien mores encountered, and in the light of all that is so terribly wrong and perverse with society, can still say in a rising affirmation: ‘Tomorrow, the sea will be calm again, clear quiet water.’

Comments powered by CComment